Why, oh why, does it keep raining?

- Published

- comments

It has been an extraordinarily wet summer

If you want something to blame for the appalling weather, look up as you raise your umbrella and imagine that high above the rain clouds a great river of wind is flowing through the upper atmosphere.

This is the jet stream and its path is the cause of the repeated flooding being suffered during a British summer that has so far been one of the most miserable on record.

It was first identified by Japanese researchers in the 1920s, and then experienced firsthand by American aviators flying new high-altitude bombers in World War Two.

The jet stream, a massive but mysterious driver of our weather, usually passes along a steady path from West to East across the Atlantic - sometimes a bit to the North of us, sometimes a bit to the South.

As a relatively small island, on the borderline between the Atlantic Ocean and the European continent, the precise location of the stream matters hugely to us and right now we're on the wrong side of it.

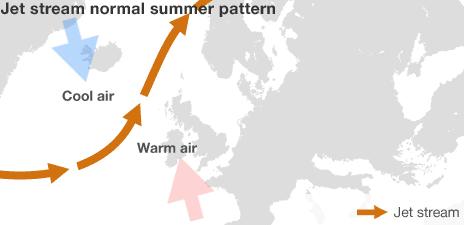

The jet stream normally sits to the north of the UK in summer, directing areas of low pressure and bad weather further north.

This giant flow of air is the result of a constant play of forces across the planet as energy passes from the warmer tropics to the cooler polar regions - and its basic direction is governed by the spin of the Earth.

What matters is where we are in relation to the stream as it surges overhead, particularly when its flow is not a neat curve but a series of massive meanders, like a river approaching the sea.

Unfortunate location

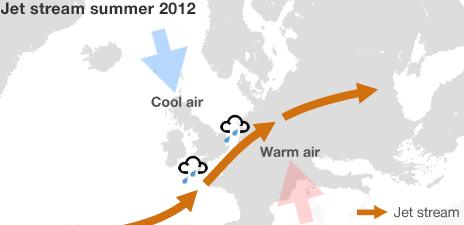

Our misfortune now is to be on the northern side of those meanders where conditions are cooler and wetter which means we in Britain keep getting hit by rain.

The bigger the meanders, the greater the chance of giant pockets of cooler, wetter air being drawn south, starting to rotate and so initiating the process that leads to storms.

The jet stream has shifted further south than usual, bringing wet and windy weather to the south of the country.

However if you read this in the US, much of which lies to the south of the jet stream, your temperatures have been soaring because the air on that side of the line is far more settled.

Normally, we would expect the pattern of the jet stream to keep shifting, for its shape to switch every few days and for our weather to change as a result.

Instead for week after week - and possibly for weeks ahead too - the meanders of the stream are sticking to the same shape so repeated rainstorms have become the norm.

Big unknown

The implications are depressing. Without some unexpected force altering the stream's pattern, it looks set to continue for a while yet.

The big unknown is why this current pattern is so static. The high-altitude winds that make up the stream are themselves still racing along but their path remains stuck in place so our battering continues.

This is one of the major puzzles for weather specialists and the science behind this is fairly young.

Dr Mike Blackburn of the National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the University of Reading admits that the reasons for a static pattern of the flow remain unclear.

"We haven't discovered why the meanders get locked into position as they are now," he told me.

One attempt at an explanation involves so-called Rossby Waves, named after the Swedish meteorologist Carl-Gustav Rossby whose research was published back in 1939.

This is no comfort as the forecasts continue to be grim, but it is a measure of the complexity of the physics involved - how air moves in waves, why certain patterns form - that more than 60 years later scientists are still wrestling with the question of how the jet stream operates and what shapes it.

Dr Blackburn and his colleagues studied the pattern of the jet stream during the floods in June and July 2007 and found it to be similar in appearance to now.

So it seems that if it gets locked into the wrong position, with a pattern of large waves, heavy rain is the result.

Climate change

On top of this, there is the related question of climate change. Most researchers are extremely reluctant to attribute any single weather event to global warming.

But Dr Peter Stott, a leading climate scientist at the UK Met Office, says that since the 1970s the amount of moisture in the atmosphere over the oceans has risen by 4%, a potentially important factor.

That does not sound like much but it does mean that extreme rain storms may bring more rain than before - with more moisture in the air, what goes up must come down, and the odds are worse.

"That could make the difference between a place getting flooded or not getting flooded," he said.

So there are no exact answers, just some important strands in the science and a lot more research still needed to understand exactly why our weather is so bad.

When I rang the BBC Weather Centre this morning and said I wanted to talk about the rain, a colleague answered with a single word, as if the constant storms were her fault: "sorry."