Ahoy! Your ship is being tracked from orbit

- Published

- comments

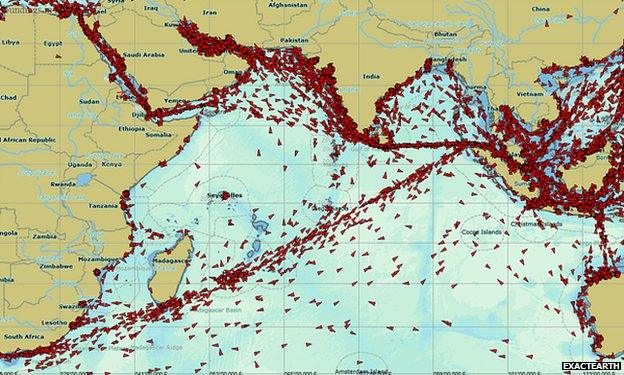

Large ocean going vessels steer clear of the Somali coast to avoid confronting pirates

The latest satellite ship-tracker goes into orbit this weekend for Canada's ExactEarth, external company.

The monitoring of vessels at sea is a fast-developing space service.

It's a market being driven presently by ExactEarth and its US competitor, Orbcomm, external.

Their satellites listen in to the AIS (Automatic Identification System) signals broadcast from vessels.

All ships over 300 gross tons (and many passenger ships) are mandated to carry transponders that push out data that includes not just position, course, and speed, but also information about a ship's type, draught, cargo - even its eventual destination.

AIS was established in the first instance as a safety system - something maritime agencies and ship operators themselves could use near shore to keep tabs on who was doing what in local waters.

Its limitation is that communication with coastal receiving stations is line of sight, meaning it's not possible to track vessels once they've gone out into the open ocean. Hence the enterprise of also putting receiving stations in orbit.

"It's interesting. Before satellite AIS came along, you'd talk to people and they'd just assume that ships were tracked wherever they went in the world. But the reality was that there were 60,000 ships out there carrying nine trillion dollars' worth of cargo, and when the captain went over the horizon, unless he sent a signal, no-one knew where he went. That's all changed now," says ExactEarth's John Allan.

The company claims its exactView-1 satellite, external will be the most performant platform yet launched.

The spacecraft is British-built, assembled by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited in Guildford. It AIS receiving equipment is also UK built - developed by the European division of Com Dev (which part owns ExactEarth) at its Stoke Mandeville base in Buckinghamshire.

It was apparent just from the AIS data that the Costa Allegra was in trouble

Doing ship-tracking from orbit is not straightforward. In some of the busiest waterways, it can be very difficult to disentangle the signatures of the individual vessels.

Rob Goldsmith from Com Dev Europe explained: "One of the problems with AIS is that it was designed as a terrestrial system - ship to ship, and ship to shore. It's a VHF signal and it uses something called Self-Organized Time Division Multiple Access, which means that within a communication frequency, each ship will be allocated a slot and it will co-ordinate with all the others so there is no interference.

"That's fine over a 50-70-nautical-mile cell, but from space you see a lot of these cells and they collide - you get a lot of noise. But we have a very clever algorithm. Our satellites capture the signals and download them to the ground where a big computer separates them."

ExactEarth expects the next-generation receiver on the new satellite to finesse this process even more.

The exactView-1 spacecraft is the smaller of the three satellites mounted for launch on Sunday

There are lots of applications for this type of data.

Safety at sea is an obvious one. If a vessel gets into trouble, the maritime authorities can see very quickly where that ship is and those that are closest to it and might be able to offer assistance.

"In the AIS data, you get course over ground information (the direction in which it's moving) and heading (the direction the ship's pointing). These can tell you a lot about what a ship is doing," says John Allan.

"You may remember the Costa Allegra, which had a fire about two weeks after its sister ship, the Costa Concordia, ran aground.

"The fire knocked out the engine and the ship started drifting, and you could see that in the AIS data. The ship went side on in the current, but its heading was about 90 degrees different.

"Just by looking at the AIS data, you could tell there was something wrong with the vehicle.

"Now, if you were a coastguard and you saw that behaviour in a supertanker, it would certainly pique your interest."

AIS information is being used to challenge owners whose ships take dangerous shortcuts or fish in restricted zones.

It's also being used in the effort to combat piracy, by enabling the authorities to manage and monitor convoys of ships passing through high-risk waters. Nato is using satellite AIS to monitor the situation off the Somali coast.

The killer application in the future will be to put an AIS receiver on a radar satellite.

Radar sees through cloud and can picture the sea surface day or night.

Plans are afoot to put AIS on radar satellites, which can see the ocean surface whatever the weather

Not only then would you have the identification data but you could tie this directly to the imagery evidence.

This would allow you to check the vessel was indeed the type of ship its AIS transmission claimed it to be; or, in the opposite scenario, investigate why a big ship picked up on radar was not broadcasting its status.

It has been known, for example, for traffickers to turn off their AIS to try to hide their activity.

The Spanish government's first radar satellite, Paz, external, due to launch next year will carry an AIS receiver.

There is a proposal also for the forthcoming British NovaSAR radar satellite to be fitted with such equipment.

And the European Space Agency recognises the benefits of joining the two technologies and is talking about including AIS on one of its future Sentinel radar platforms, external.

UPDATE - 22/07/12: exactView-1 launched successfully on its Soyuz rocket at 06:41 GMT, Sunday, 22 July. You can read more about the other satellites that launched with exactView-1 here, external.