The independent coffee republic of Totnes

- Published

A very British insurrection is under way over plans to bring the first branch of a major coffee chain to a small Devon town. But why are coffee chains such a battleground?

At half nine on a bright morning the aroma of arabica gently percolates through Totnes's narrow lanes and alleys.

That smell of roasting beans is difficult to escape. In this settlement of fewer than 8,000 souls there are 41 different places to buy a hot cup of the stuff.

And yet plans to open just one more coffee outlet have provoked fury - opening up a dispute as bitter as the darkest espresso.

The latest addition to the town's High Street will be a branch of Costa - the first coffee chain to breach the citadel of a community fiercely proud of its independently owned outlets.

So far 5,749 people - equivalent to three-quarters of the town's population - have signed an anti-Costa petition and pledged to boycott the new branch. Its approval by South Hams District Council was greeted by a 150-strong group of placard-wielding demonstrators who marched through Totnes's streets in protest.

Totnes boasts 41 independently owned coffee outlets

Though they have no recourse to appeal, the campaigners stubbornly refuse to give in amid apocalyptic warnings that Totnes risks becoming a "clone town".

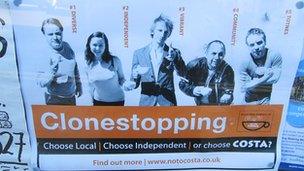

Posters bearing the legend Clonestopping - featuring local baristas posing in the style of the film Trainspotting - adorn windows of homes and commercial premises.

A glance at the Yellow Pages might have given the council warning. With names like Totnes People's Cafe, Food For Thought and The Curator Cafe, many of the coffee shops share an aesthetic of nonconformism.

Some of the many shops Totnes residents can visit for a caffeine fix

Totnes is not exactly typical of a small British town. Like Hebden Bridge or Glastonbury, it has long hosted incomers attracted by its eco-friendly and New Age reputation.

Shops along its High Street selling crystals, alternative therapies and joss sticks easily outnumber those with the shopfronts of major retail brands. The building earmarked by Costa was previously occupied by Greenlife Organic Wholefoods, which had to vacate the site for larger premises.

Anti-Costa campaigns have gained support in Totnes

And yet it is precisely this distinctiveness that opponents of Costa's arrival fear is at risk. Far from being virulent anti-capitalists, most insist they are anxious to preserve the town's unique selling point.

Totnes's 70-year-old Mayor Pruw Boswell is a stern critic of Costa - along with every other member of the town council - and is in opposition to the district authority, whose planning committee approved the chain's arrival.

Over a freshly infused white filter coffee in a cafe called Brioche, she argues that the town's 120,000 annual visitors come precisely because it caters to a gap in the tourist market.

"As a woman, when I go on holiday I want to go for a chocolate cake and a coffee and let my hair down," she argues. "I don't want to do all the things I can do at home. What makes us different is the number of independent places here."

There is something about coffee that puts it at the vanguard of protest movements. Naomi Klein's anti-corporate bible No Logo was harshly critical of Starbucks conduct in particular.

The chain has faced protests over accusations that it ran sites at a loss to squeeze out the opposition and the chain's shopfronts are often among the first to be smashed when anti-capitalist protests turn violent. Starbucks has consistently denied doing anything improper and argues that its expansion increases overall demand for coffee.

In the US, many neighbourhoods have fought similar battles to that in Totnes. But a free market advocate would note that if people don't want chain shops spoiling their town there's a simple solution - don't patronise them.

On both sides of the Atlantic there seems to be an emotional resonance over coffee shops that doesn't apply to other businesses. Pubs have something of the same status in the UK.

A cynic might question why no-one in Totnes protested about the arrival of WH Smith, say, and its impact on the town's independent newsagents.

"The difference is that WH Smith is never going to be a community hub," says Holly Tiffen, 40, organiser of the Totnes Independent Coffee Festival and a leading light in the campaign to have Costa's planning application rejected.

For some people cafes play a place in social life which might be fulfilled elsewhere by the pub, town hall or community centre.

In 2009, Ian Gregory, 47, left his previous career as an account manager at a shower door manufacturer, seeking a change in the pace of his life. He moved to Totnes to open up the Fat Lemon Cafe and devote his life to coffee.

"It's an art," he says. "The expectations are high. You really have to know what you're doing, especially because there's so much competition around here."

Gregory fears his expertise will have been acquired in vain, however, when Costa comes to town. He believes it offers a homogenised, lowest common denominator brew.

There is some evidence to support the idea that a significant proportion of consumers are risk-averse when it comes to coffee. A recent study for the market research company Mintel found 32% said they were "not very adventurous" when it came to ordering drinks, 33% stuck to a favourite brand and 31% "don't tend to choose anything new/different".

For its part, Costa insists its new branch "will not be a threat and instead aims to add new vibrancy by complementing the local offering". South Hams District Council says the decision to approve the building's change of use from a retail unit to a cafe was made on "planning grounds alone".

Many of the passers-by along the High Street outside the proposed Costa, however, are opposed.

"I shall never go in there," barks artist Ishvara D'Angelo, 81. "Chains like this suck the life out of communities," argues Alexander Hodgson, 50, an environmental consultant. Retired Rick Hughes-Weston, 68, shakes his head: "We're going to become like everywhere else."

Some visitors, too, express dismay. "I love Costa," says 66-year-old social services worker Sue Downton, a regular of the chain in her native Plymouth. "But not here. People come through to Totnes because it's different."

The closest expression of anything other than outright hostility comes from Andy Garner, 55, owner of Totnes Television and Electrical - and his attitude towards Costa is of resignation rather that enthusiasm.

"It's a difficult one," he shrugs. "At the end of the day, it's within the law. Whatever happens, it's going to be a wake-up call for the town."

Not that Totnes needs to wake up in order to smell the coffee. As this Ealing comedy-like conflict intensifies, that scent of espresso still filters through the air.