Space - the new rock and roll

- Published

- comments

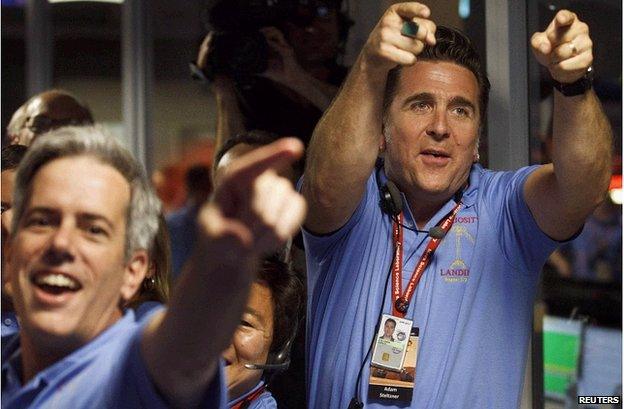

The reaction from the Nasa control room as the robot landed

"I hope to do something as great in my life in the future, but if I don't - this will have been enough."

Adam Steltzner has had a little time to reflect on the historic touchdown of the Curiosity rover on Mars, although he confesses the adrenaline of the past few days means he hasn't himself yet landed back on Earth.

The man who led the Nasa team that devised the "crazy" system to get Curiosity on the ground is still buzzing.

"It is a triumph. It is a triumph of ingenuity and engineering, and it's something the team should be very, very proud of," he says.

For a few days, Steltzner became the face of this mission.

His engaging personality and presentation, allied to his rock and roll looks, meant he was a natural magnet to the news cameras.

In those remarkable pictures from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory control room, he was the one pacing around and pointing.

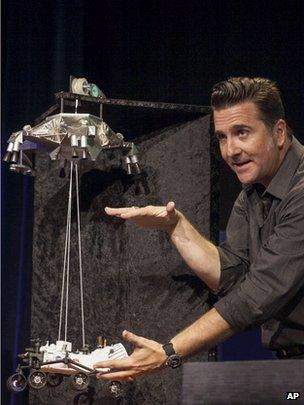

Steltzner and the Curiosity landing system now go their separate ways

And all eyes were on him - the master of ceremonies.

The worst part, he says, was waiting for the rover in its descent capsule to touch the top of the atmosphere.

About nine minutes out, the capsule detached from the spacecraft that had shepherded it from Earth.

There was then a hiatus before the real action began. "Those nine minutes were horrid."

If you haven't watched the moment of touchdown, you can see it in the video at the top of this page.

"I wanted three confirmations that we were safe on the ground," Steltzner told me.

"I had three different people looking at three different pieces of data. The first thing you heard was 'Tango Delta Nominal', which was touchdown nominal coded up so the world would not erupt into applause.

"Then Dave Way said 'RIMU stable', which meant the inertial measurement unit on the rover indicated that it was not moving - so, that told us we weren't dragging the rover with the skycrane.

"And then I looked over at Brian Schratz who was sitting in the EDL comm. His orders were to count to 10 and then tell me if he was still getting persistent clean UHF signal, which meant the descent stage wouldn't have fallen back on the rover. He said 'UHF persistent'.

"I pointed at Al Chen who called out 'touchdown confirmed'. The room erupted and the world learned we'd just made it to the surface of Mars."

Steltzner wanted to be sure the skycrane descent stage had not crashed on top of the rover

Where do you go after you've done something like that? Steltzner is unsure. He's out of a job now. He has to write up a report on the landing and hand it to Nasa's top brass, but then he's got to find another project.

"Will engineer for food", is how he advertises his skills.

The frustrating part about all this is that the extraordinary landing system devised by Steltzner's team appears to be a one shot affair.

Adam Steltzner: It should inspire everyone

The skycrane was supposed to be used again in 2018 to put a pair of rovers on Mars, but then this joint European and US plan was scrapped. Technical drawings can get filed away somewhere, but the expertise that makes them real is all too often allowed to just drift apart.

Instead of building on success, space agencies have an infuriating habit of going back to zero and starting all over again.

I know this is an oversimplification, but it seems that everything must be bespoke. We design something once and then we design something different. This appears to be the way with planetary exploration at any rate.

Contrast the approach with communications satellites which come off a production line. Their unit costs are substantially less as a consequence.

Given the opportunity, Adam Steltzner is in no doubt where he'd like to land next: "We should be going to Europa, the moon of Jupiter that is the most likely place in the Solar System to have existent life."