Climate change may boost frog disease chytridiomycosis

- Published

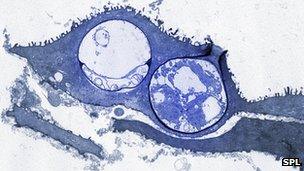

The Cuban tree frog is one of many species affected by the fungal disease chytridiomycosis

More changeable temperatures, a consequence of global warming, may be helping to abet the threat that a lethal fungal disease poses to frogs.

Scientists found that when temperatures vary unpredictably, frogs succumb faster to chytridiomycosis, which is killing amphibians around the world.

The animals' immune systems appear to lose potency during unpredictable temperature shifts.

The research is published in Nature Climate Change journal, external.

Chytridiomycosis, caused by the parasitic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), was identified only in 1998.

It affects frogs and their amphibian relatives - salamanders, and the worm-like caecilians - and has caused a number of species extinctions.

"I'm not convinced that the effect we've discovered could be considered responsible for declines or extinctions in the ways way that the spread of Bd can be considered responsible," said Thomas Raffel, lead scientist on the new research.

"It might be, however, that climate change has sped up the decline or extinction after the parasite arrived," the Oakland University researcher told BBC News.

Variable success

Over the years, various teams of scientists have conducted a whole raft of experiments to find, for example, whether Bd is more active in warm or cold temperatures.

Bd spores spread from the skin of amphibians

The new research looked at what happens in a more real-life situation - when chytrid fungus is actually on a vulnerable frog.

And the key variable the scientists looked at was variability of temperature, rather than temperature itself.

Cuban tree frogs (Osteopilus septentrionalis) infected with Bd were kept under various conditions.

In some, the temperature was kept constant at either the bottom or top of their natural range (15C and 25C (59F and 77F)).

In others, the temperature was switched predictably between the two values, mimicking the natural day-night cycle; and in a third set, the temperature was switched between 15C and 25C unpredictably.

On its own, the fungus fared better in cooler conditions, and when the temperature changes were regular.

But when it was already on the frogs, the pattern was reversed; the fungus grew faster under unpredictable temperature change.

The explanation is that being a simpler organism, it is able to adapt faster than the frogs' immune system.

Previous research has found alterations in frogs' white (immune) cells due to temperature changes.

But Dr Raffel suggested it was hard as of now to project what this meant for amphibians and the chytrid threat.

"There's a lot of observational evidence that climate change is leading to increased variability and unpredictability of temperature and precipitation, and it's entirely possible that the kind of effects we observed could become more important in the future," he said.

"But I think it's really difficult to make extrapolations - partly because work needs to be done with additional species, and also because we haven't done the experiments yet that would allow us to make predictive models in a quantitative way."

Herpetologist Benjamin Tapley from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), who was not involved with the study, also suggested it was too soon to draw strong conclusions.

"This paper presents some interesting and potentially useful information on climatic shifts and Bd," he said.

"But there are now over 7,000 species of amphibian, and the relationship between each of these potential hosts and Bd will be species-specific; so I would be cautious of drawing broad scale assumptions."

Consuming problem

In a separate piece of research, scientists have produced more evidence that Bd is being spread by trade - in this case, by the movement of the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) for food.

The bullfrog carries Bd, but appears naturally immune.

In a paper in the journal Molecular Ecology, external, the researchers documented that a Brazilian strain of Bd had been transported to Japan, discovered various strains on frogs being sold in Asian food shops in the US, and found novel strains created by sexual reproduction.

"Our data suggest that chytrid strains have been vectored across the globe by bullfrogs, which may have ultimately led to the disease being so widespread," said Timothy James from the University of Michigan.

"A lot of the movement of this fungus is related to the live food trade, which is something we should probably stop doing."

Three years ago, Australian researchers calculated, external that more than a billion frogs were raised each year for human consumption.

Follow Richard on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published10 April 2012

- Published8 November 2011

- Published1 June 2011