Arctic sea ice reaches record low, Nasa says

- Published

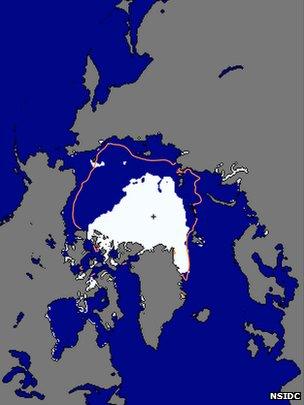

The sea ice extent at 26 August (white) is markedly different from the 1979-2000 average (orange line)

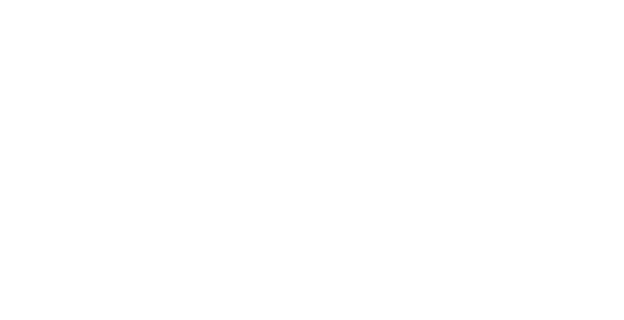

The Arctic has lost more sea ice this year than at any time since satellite records began in 1979, Nasa says.

Scientists involved in the calculations say it is part of a fundamental change.

What is more, sea ice normally reaches its low point in September so it is thought likely that this year's melt will continue to grow.

Nasa says the extent of sea ice was 1.58m sq miles (4.1m sq km) compared with a previous low of 1.61m sq miles (4.17m sq km) on 18 September 2007.

The sea ice cap grows during the cold Arctic winters and shrinks when temperatures climb again, but over the last three decades, satellites have observed a 13% decline per decade in the summertime minimum.

The thickness of the sea ice is also declining, so overall the ice volume has fallen far - although estimates vary about the actual figure.

Joey Comiso, senior research scientist at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center, said this year's ice retreat was caused by previous warm years reducing the amount of perennial ice - which is more resistant to melting. It's created a self-reinforcing trend.

"Unlike 2007, temperatures were not unusually warm in the Arctic this summer. [But] we are losing the thick component of the ice cover," he said. "And if you lose [that], the ice in the summer becomes very vulnerable."

'Inevitable death'

Walt Meier, from the National Snow and Ice Data Center that collaborates in the measurements, said: "In the context of what's happened in the last several years and throughout the satellite record, it's an indication that the Arctic sea ice cover is fundamentally changing."

Professor Peter Wadhams, from Cambridge University, told BBC News: "A number of scientists who have actually been working with sea ice measurement had predicted some years ago that the retreat would accelerate and that the summer Arctic would become ice-free by 2015 or 2016.

"I was one of those scientists - and of course bore my share of ridicule for daring to make such an alarmist prediction."

But Prof Wadhams said the prediction was now coming true, and the ice had become so thin that it would inevitably disappear.

"Measurements from submarines have shown that it has lost at least 40% of its thickness since the 1980s, and if you consider the shrinkage as well it means that the summer ice volume is now only 30% of what it was in the 1980s," he added.

"This means an inevitable death for the ice cover, because the summer retreat is now accelerated by the fact that the huge areas of open water already generated allow storms to generate big waves which break up the remaining ice and accelerate its melt.

"Implications are serious: the increased open water lowers the average albedo [reflectivity] of the planet, accelerating global warming; and we are also finding the open water causing seabed permafrost to melt, releasing large amounts of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, to the atmosphere."

Threats and opportunities

Opinions vary on the date of the demise of summer sea ice, but the latest announcement will give support to those who err on the pessimistic side.

A recent paper from Reading University, external used statistical techniques and computers to estimate that between 5-30% of the recent ice loss was due to Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation - a natural climate cycle repeating every 65-80 years. It's been in warm phase since the mid 1970s.

But the rest of the warming, the paper estimates, is caused by human activity - pollution and clearing of forests.

If the ice continues to disappear in summer there will be opportunities as well as threats.

Melting ice is causing the Arctic to warm much faster than the rest of the planet

Some ships are already saving time by sailing a previously impassable route north of Russia.

Oil, gas and mining firms are jostling to exploit the Arctic - although they're being strongly opposed by environmentalists. Greenpeace has been protesting at drilling by the Russian giant Gazprom.

Among the many threats, the warming is bad for Arctic wildlife. Thanks to the influence of sea ice on the jet stream the changes could affect weather in the UK.

The changes - if they happen - could unlock frozen deposits of methane which would further overheat the planet.

Warmer seas could lead to more melting of Greenland's ice cap which would contribute to raising sea levels and changing the salinity of the sea, which in turn could alter ocean currents that help govern our climate.

- Published21 August 2012

- Published24 April 2012

- Published20 April 2012