Dawn probe leaves Asteroid Vesta

- Published

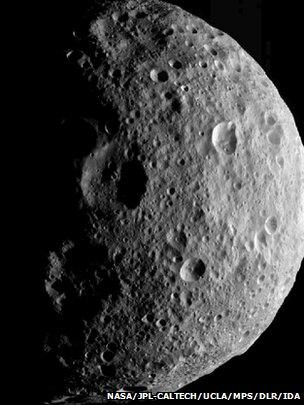

Looking down on the northern pole: Sunlight is finally breaking into the shadows

The US space agency's Dawn satellite has left the giant Asteroid Vesta after 13 months of study.

A signal from the probe confirming that it had escaped the gravitational bounds of the 530km-wide rock was received by Nasa on Wednesday.

The spacecraft's ion engine is now pushing it on to an even bigger target in the belt of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter - the dwarf planet Ceres.

Dawn, external is expected to reach this 950km-wide body in early 2015.

Before departing on its long cruise to the new destination, the probe trained its camera system on Vesta's northern pole.

The pictures reveal mountains and craters that are being seen for the very first time. Only now, as Dawn heads away, has the Sun risen high enough in the sky to illuminate the highest latitudes.

Scientists are poring over the images to see what interpretation they can put on the terrain.

Vesta has the appearance of a punctured football - the result of two mighty impacts that removed huge volumes of rock from its southern pole.

These collisions sent shockwaves rippling across the asteroid, producing a deep system of troughs that extends around the object's equator.

Researchers have speculated that this disturbance might also be reflected in the features hitherto obscured at the northern pole.

However, Dawn's principal investigator Prof Chris Russell said a definitive statement on such matters would have to wait on a detailed assessment of the new pictures.

"We haven't got together to discuss it carefully yet," he told BBC News. "[The region] is not as jumbled as I had expected; it's more subtle than I had expected - but the people who are experts in this particular area do feel that there is an effect of the southern impact."

An elevation map of the southern pole showing the location of two big impact basins. The largest, known as Rhea Silvia, measures some 475km in diameter

The Dawn mission has returned a great swathe of data to transform our understanding of Vesta.

Before the probe's arrival in July last year, the best views of the asteroid were some fuzzy pictures acquired by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Dawn studied in detail the pattern of minerals exposed at Vesta's surface and also mapped the diverse geological features shaping its terrain.

These observations have enabled scientists to elucidate a history for the colossal rock.

They now regard it as a unique body - the only remaining example of the original objects that came together to form the rocky planets, like Earth and Mars, some 4.6 billion years ago.

It is clear now that Vesta has a layered interior, with a metal-rich core that takes up some 18% of the body by mass.

All of the other objects like it at the Solar System's birth were either obliterated in the intense collisional environment that existed back then or were incorporated into successively larger aggregations of material that eventually produced the planets we recognise today.

Perhaps the stand-out discovery is the definitive association that can now be made between Vesta and the howardite-eucrite-diogenite, or HED, class of meteorites that regularly fall to Earth.

From telescopic observations, researchers had always suspected these meteorites came from Vesta. But the signatures of pyroxene - a mineral rich in iron and magnesium - in those meteorites have now been matched precisely with the mineral signatures spied in Vesta's surface by Dawn's instruments.

It is highly likely that much of the HED material was thrown off Vesta in those two big impacts at the southern pole.

"We have used those meteorites and their chemical analysis to tell a story about the formation of the Solar System and its evolution, and if that was wrong we'd have had a lot of explaining and new work to do. The fact that it is right, and we've confirmed it, is really very good. It makes our lives a lot simpler," said Prof Russell, who is affiliated to the University of California, Los Angeles.

It will take Dawn about two-and-a-half years to reach the dwarf planet Ceres

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published11 May 2012

- Published23 March 2012

- Published13 October 2011

- Published22 July 2011

- Published22 July 2011

- Published19 July 2011

- Published17 July 2011

- Published13 June 2011