So remote, it could pass for Mars

- Published

- comments

Ny Alesund is beautiful and remote

At 79 degrees North, deep inside the Arctic Circle, a research base offers a fascinating glimpse of what life may be like in some future human outpost on a distant planet.

As the world's most northerly permanent polar settlement, the huddle of buildings at Ny Alesund in Svalbard has the feel of a cross between a department of the United Nations and a miniature university campus.

Operated by the Norwegians to provide support for frontline Arctic science, this community of scientists from nearly a dozen different countries nestles on a windswept shore beneath forbidding mountains.

It is a world of stark beauty: the howls of huskies echo off the cliffs, a bearded seal perches on an iceberg and fulmars dive and swoop over the waves.

The midnight sky is still bright enough to read by, a white-gold sun dipping only briefly below the horizon.

In fact the place is so unearthly, so Martian, that the American space agency Nasa chose it as a proving ground for its latest expedition to the Red Planet.

The teams now running the robotic vehicle Curiosity on Mars ventured here because the terrain was judged suitably alien.

No place for man

Initially, as a new arrival, the efficiency of the staff and the triple glazing of the warm rooms make it easy to forget that all of us are existing in a spot that Nature never really intended for mankind.

Warnings about polar bears are a constant reminder of the hazards of living in what anyone might sensibly consider to be well inside another creature's realm.

Polar bears are a threat

A guide to newcomers states on its cover: "Read this and avoid to become extinct".

A particularly bold polar bear ambled through the base last year, for some reason sniffing a line of bicycles.

A video clip, external shows it passing the centrepiece of the community, a giant bust of the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, a man with his own fair share of polar bear scrapes.

And having studied the video, I now realise the animal went right past the building I'm staying in.

"If you go out filming," we are told, "never leave the base without someone with a rifle and if you are on the base always be ready to rush for shelter should a bear approach."

So a golden rule of survival in this settlement is that every building must have its front door unlocked - and that includes those of the hosts, the Norwegian Polar Institute, and of the French and Germans, the British, the Indians, the Chinese and many others.

Yes, an extraordinary range of countries is represented here, each committed to scientific research but also perhaps ensuring a footprint is planted in a region of immense potential value.

China's building is unmistakeable because its entrance is graced by a pair of stone lions.

But the atmosphere could not be more benign. In fact this scenario of unlocked laboratories and sleeping quarters is probably as close to a global utopia as we're ever going to get.

Generations of UN leaders would have dreamed of having so many nations of the world gathered together in one spot with so few keys.

People generally seem happy to rub along though a test of that is thrown up by another rule: that everyone - however fond of their own home dishes - has to eat together in a communal canteen.

It does make for a self-evidently international atmosphere - Italians sitting close to the Indians, Chinese at the neighbouring table to the Germans.

No modern communications

A steam train once ferried coal out

But I cannot help noticing that after exchanging polite smiles in the hot food queue, and nodding to one another over the cheese board, the national groups tend to stick together.

But they are at least talking. No one is head down, solitarily hunched over a tiny electronic device, alternately stabbing at a screen and a plate of pasta. All such gadgets are banned.

This is a land without mobile phones, WiFi or Bluetooth. It feels like a throwback to life before the 80s.

The reason for the ban stands not far from the runway.

A vast satellite dish scans the heavens for signs of those bizarre deep space phenomena known as quasars - the huge structure twitching and turning around the clock.

Despite its size, the instrument is so sensitive that the whole base has to be starved of the oxygen of mobile communication.

As we got off the plane, cameraman Duncan Stone, producer Mark Georgiou and I went through the strange experience of not turning on our mobile phones. We felt somehow naked.

Land of glaciers

Living here requires adjustment. If the night-time light falling through my curtains is too bright, I get up and enjoy the view from my window.

The explorer Amundsen is commemorated

It is an ice scientist's heaven: I can count eight glaciers flowing down between the mountains.

On a slope nearby are the remains of an abandoned mine.

Researchers were not the first to land here. Whaling was once a big lure, then coal, extracted until a terrible accident in 1963.

A steam engine and its trucks stand rusting on a railway used to ferry the black gold to the ships.

Fossil fuels once made this place and may transform the Arctic in decades ahead.

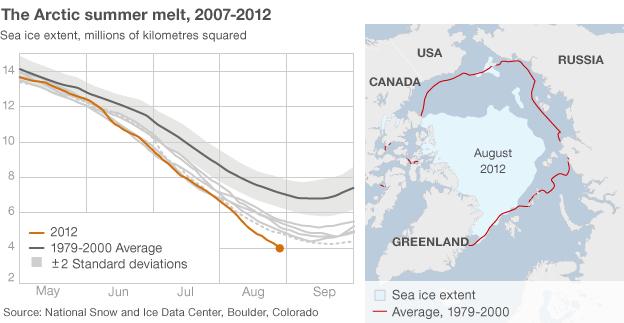

For now their effect on the atmosphere is being patiently measured by the scientists.

The Arctic world can mean many different things: raw nature, untapped geological treasure, essential research into climate change. And of course life beyond the usual. Take your pick.

You can see our coverage from the Arctic on BBC News on Friday - on television, on radio and online.

Photographs by Mark Georgiou and Duncan Stone.