X-ray imaging tricks increase resolution and cut dose

- Published

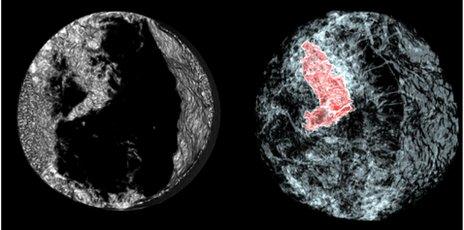

The image compares a conventional CT scan (l) and a scan with the new approach and 1/25th the dose

An international research team has proposed a way to make high-resolution, 3D images of breast tissue while reducing the delivered X-ray dose.

Breast tissue is particularly susceptible to X-ray radiation so 3D scanning is generally not employed.

Now a team reporting in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external suggests a different form of X-rays and a new image analysis approach.

However, new compact X-ray sources are needed to bring the idea to the clinic.

Taken together, the two improvements lead to high-resolution 3D images while reducing the delivered dose to just 4% that of standard "computed tomography" (CT) scans.

A cancer charity called the work "a promising step" toward earlier, more accurate breast cancer diagnosis.

A phenomenally successful technique in X-ray scanning over the past half-century, CT scans are made with a number of X-ray images taken from various angles that are analysed to yield a 3D view.

The approach is reserved for the imaging of parts of the body for which these multiple X-ray exposures is deemed safe, generally excluding "radiosensitive" breast tissue.

Instead, what is known as dual-view mammography is employed, producing two conventional X-ray images of the breast - a methodology that is known to miss 10-20% of tumours.

One to watch

Recent years have seen growth in the use of what is called phase contrast imaging, which measures not only how much X-ray light gets through tissue, but also in a sense how long it takes to get there. This yields a far clearer picture of subtle changes in density that can show tumours.

Now researchers from the US and Germany working at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France have refined the phase contrast approach using what they call equally sloped tomography.

The CT scan is the "gold standard" among X-ray techniques but presents a risk to breast tissue

The improvement is in the mathematics used to analyse X-ray images - instead of taking a number of images at evenly spaced angles around a sample, EST takes images at irregular angle intervals and uses improved equations to reconstruct the 3D representation.

Co-author of the study Paola Coan of Ludwig Maximilians University explained that an analogy of the process is a watch.

"Instead of having a hand that measures every second, we have a hand that follows a certain scheme, the first hand movement is 1.2 seconds, then 0.7 then maybe 0.9, but at the end, thanks to EST, we still measure perfectly the minute," she explained to BBC News.

"With this mathematical trick we avoid interpolation and the image looks better - we even need to take fewer radiographs to reconstruct the computed tomography full image."

Testing the approach at the ESRF with a whole mastectomied breast, the team showed that they could acquire images as sharp as those of conventional CT scans using just a quarter of the delivered X-ray dose.

But they carried the work further by using the ESRF's capabilities to run the same test with higher-energy X-rays. Soft tissue is more transparent to these "harder" X-rays and therefore less radiation is absorbed.

As members of the team showed in an article in Physics in Medicine and Biology, external in April, images of a quality comparable to standard CT can be acquired with harder X-rays corresponding to just a sixth the radiation dose.

In combination, the techniques result in the resolution of a full CT scan while delivering a dose just 4% as large.

"We've demonstrated that by combining X-rays at high energy plus this sophisticated CT reconstruction, we're able to perform a complete CT with high resolution, but with a dose that is much lower than than in conventional CT and potentially... lower than dual-view mammography," Prof Coan said.

"This is an extraordinary result."

However, she added that compact, high-quality X-ray sources capable of the higher-energy regime are still necessary to get the technique established in the clinical setting, a research effort that is underway for a number of industries.

Emma Smith, Cancer Research UK's senior science information officer, said: "The results of this study show that powerful new technology could give doctors a more detailed image of the breast without increasing the dose of radiation."

"This research is still at an early stage and the technique has not yet been tested to see if it's safe and effective in women, but it is a promising step towards doctors being able to spot breast cancer earlier."

- Published7 June 2012

- Published26 October 2011

- Published23 September 2010