Chalara ash dieback outbreak: Q&A

- Published

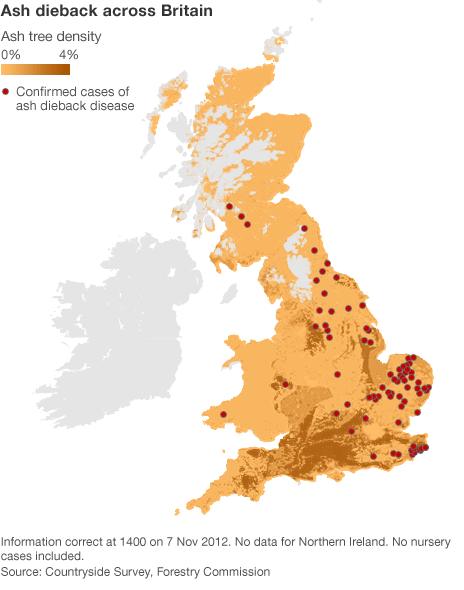

Confirmed cases in East Anglia signalled the disease's arrival in the UK's natural environment

The recent confirmed cases of Chalara ash dieback means it has become the latest threat to UK trees.

Within the UK's woodlands, ash is the third most abundant species of broadleaf tree, covering 129,000 hectares.

However, common ash (Franxinus excelsior) is very successful at growing in most landscapes - from urban scrubland to exposed uplands.

Experts warned that if ash dieback was to become widely established in the UK, the impact could be as serious as the 1970s outbreak of Dutch elm disease, which saw millions of trees destroyed.

But what do we know about Chalara ash dieback, caused by a fungus known as Chalara fraxinea?

And what steps can be taken to limit the impact of this potentially devastating threat?

What is Chalara fraxinea?

It is the fungus that has been identified as being the culprit behind the current ash dieback epidemic in Europe.

It was first described in 2006, and was first believed to be a form of a species of fungus (Hymenoscyphus albidus) that had been known to scientists since the mid-19th Century.

H.albidus is a fungus that is widespread throughout Europe, but is benign and is not responsible for causing tree disease.

However, further research in 2010 revealed that Chalara fraxinea is, in fact, a form of H. pseudoalbidus, which is closely related to H. albidus.

It has since been identified as being the cause for ash dieback in Europe since the early 1990s, when the first cases were recorded.

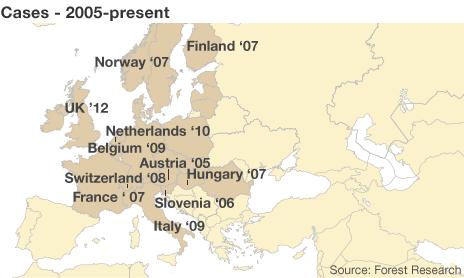

What is the fungus's current distribution?

It has only been recorded in Europe. The latest confirmed cases means the UK joins a long list of nations: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden and Switzerland.

The common ash, Franxinus excelsior, is widespread throughout much of Europe.

Ash dieback started to be noticed in the 1990s although it it only more recently that scientists discovered that the fungus Chalara fraxinea was the cause.

Dieback caused by the disease, which can be windborne, began to be reported more widely in the first few years of the 21st Century.

Plant protection body EPPO added Chalara ash dieback to its alert database in 2007 and the spread of reported outbreaks has continued.

What ash species are at risk?

So far, the following species - which are found in woodlands, parklands, ornamental gardens and back garden - have been identified as natural hosts: European (or common) ash; weeping European ash; narrow-leafed ash; manna ash; black ash; green ash; white ash; Manchurian ash.

What are the symptoms?

The most visible sign that a tree is infected is bleeding sores and cankers on the bark, and discolouration of the underlying sapwood.

The sores often surround branches in the infected area of the tree, causing the dieback of shoots, twigs, branches and smaller stems.

The disease has also been shown to infect ash tree leaves, appearing as blemishes.

There are numerous other diseases that display similar symptoms, making it difficult to identify for most people.

Anyone who feels they have identified an infected tree should contact one of the UK's tree health agencies, external.

Where has it been found in the UK?

The disease has now been confirmed at 115 sites, with woodlands in Norfolk, Suffolk, Kent and Essex among the worst affected, according to data released by officials on 7 November.

In recent weeks, 100,000 ash trees have been destroyed. Initially, the disease had only been confirmed in the "natural environment" in East Anglia.

In a statement, the department added that scientists "believed that the disease... may have been present for a number of years".

How did it get into the UK's natural environment?

The infection biology of Chalara fraxinea is not fully understood.

Evidence suggests that the majority of infections first occur on ash trees' leaves, indicating that the disease's main form of spread is via wind dispersal.

This adds weight to the idea that the most probable cause of the outbreak was a result of spores being carried by the wind from mainland Europe.

Movement of contaminated soil or plant material is also considered to be another possible pathway.

What are the implications for wildlife?

Data from National Inventory of Woodland and Trees shows that ash is the third most abundant broadleaf species in the UK's woodlands.

In areas where ash is the predominant woodland species, the loss of the trees would change the area's ecology.

This could pose a threat for other woodland species that depend upon ash for food or shelter, such as moths.

"Dusky thorn (Ennomos fuscantaria) is a particularly good example, the larvae feed on ash," explained Chris Panter, from the University of East Anglia.

"The larvae of another moth, the centre-barred sallow (Atethmia centrago) feeds on ash buds and flowers.

He told BBC News: "Both species are quite widespread, but are designated as rare or declining, having apparently declined significantly (over the past three decades).

How ash dieback could threaten Britain's wildlife What is being done to stop ash dieback becoming widely established?

The strategy to tackle tree disease or pest outbreaks generally follows a four-stage process:

Prevention - such as border checks to ensure it does not get transported into the UK via the plant trade

Eradication - if an outbreak is confirmed in the natural environment, then steps are taken to eradicate it by felling infected trees and removing the material from the landscape, adhering to tight biosecurity controls. This is the current position of the efforts to tackle the outbreak in East Anglia

Containment - if it is not possible to eradicate the outbreak, the next step is to contain the spread disease or pest

Adaptation/control - If the outbreak spreads to the natural environment in other areas/regions, then it will become very difficult to remove the pathogen from the UK's landscape. As a result, the focus then moves to developing a strategy to limit the long-term impacts.

When an outbreak occurs, time is of the essence. The worst-case scenario is numerous outbreak "hotspots" in different regions.

The Woodland Trust told BBC News that their site manager for the area first became aware that something was wrong at Pound Farm in mid-August.

He took photos and forwarded the information to the trust's head of woodland management who, it turn forwarded it to the Forestry Commission.

The site manager then returned to the location in early September and saw that the trees in question had declined, with more - "in the hundreds" displaying signs of possible infection.

The site manager forwarded an update to the head of woodland, who made urgent contact with experts at the Forestry Commission.

It was at this point that commission researchers visited the site and confirmed the presence of the disease.

The outbreak at the Pound Farm is now being used to train commission staff, allowing them to learn how to identify infected trees.

- Published29 October 2012

- Published27 October 2012

- Published3 September 2012