Ashes to ashes: Why is dieback making the headlines?

- Published

Weeping ash: The future looks, at best, uncertain for the UK's population of 80 million ash trees

Twenty years after the first confirmed case of Chalara ash dieback was recorded in eastern Europe, the disease has arrived in the UK.

Experts say it poses a real-and-present danger to the nation's population of 80 million ash trees.

They warn that it could change the landscape in a way not seen since the height of the Dutch elm disease outbreak in the 1970s and 1980s, which saw millions of elm trees being killed or destroyed.

Since it was confirmed that it was present in woodlands in East Anglia on 25 October, the disease has received extensive media coverage and prompted the environment secretary to convene a Cobra meeting, normally reserved for national crises, and call an emergency summit on how the disease should be defeated.

Yet a quick glance at the Forestry Commission's Tree Pests and Diseases website, external shows that woodlands face a number of threats from a wide variety of pathogens.

So why has this disease, caused by the Chalara fraxinea fungus, gripped the nation's attention?

Tony Kirkham, head of the arboretum at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, said he was very surprised when he heard the news that ash dieback had been confirmed in the wider environment.

"We were all led to believe that it was only on nursery stock, which had been called back to the nursery and this had been destroyed," he told BBC News.

Keith Kirby, one of the UK's leading woodland ecologists, said he was a little surprised by the amount of publicity generated by the arrival of ash dieback on these shores.

"Although when you look back, you can see that it is a case of the public being sensitised through previous diseases and concerns about the threats to forests," he said.

"Also, I think the nature of this disease and the fact it is affecting such a common tree has played a part and it does appear that this is the thing that the forestry world has been fearing for the past 10 or 20 years - that it is the next Dutch elm disease."

Dr Kirby, now at visiting researcher at the University of Oxford's Department of Plant Sciences, is a veteran of numerous tree disease outbreaks - including Dutch elm disease (DED) - during his time with English Nature and Natural England, said that DED was still present in the UK's landscape.

"You find that elm is still surviving in hedgerows and woods, but it tends to grow to a certain size and then it gets attacked and dies back again," he told BBC News.

"I don't know if this is the case with ash dieback, whether once the tree is dead that is it and there is no survival in the roots where regrowth could happen."

Another difference between the two diseases is the way the spores are distributed. Dutch elm disease was spread by beetles, whereas ash dieback is dispersed via wind-blown spores.

"There was some evidence that under warm and dry conditions, the beetle was likely to spread further so if you had a series of wet summers, it might not have spread so much," Dr Kirby observed.

"At this stage, we do not know if there will be anything that will limit the spread of ash dieback but with wind-blown spores, it is less likely we will have a get-out-of-jail-free card."

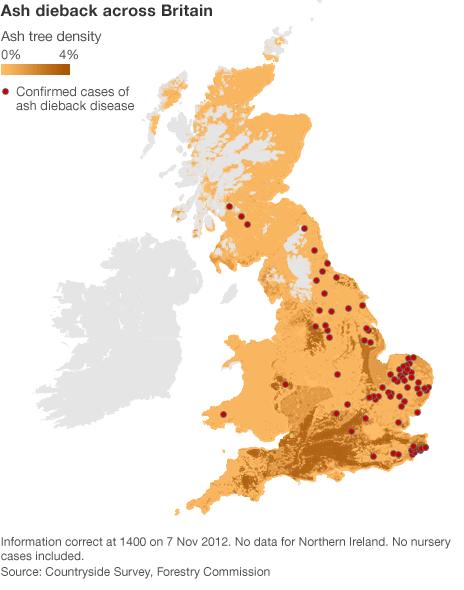

Ash dieback: Spotter's guide and maps

Another disease that hit the UK in recent years is Phytophthora ramorum. Until 2009, the disease was only detected at a very low level but then it displayed a sudden change in its pathogenic behaviour.

In the first recorded case of its kind in the world, P. ramorum was found infecting and killing large numbers of Japanese larch trees - a commercially important conifer species - in South-West England.

In 2010, it was found on Japanese larches in Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and in 2011 it was confirmed at locations in western Scotland.

Researchers acknowledged that this was a setback in the effort to tackle ramorum disease.

Another disease that has the potential to have a massive impact on UK woodlands is acute oak decline (AOD), which can infect the UK's two native oak species - sessile and pedunculate.

So far, the bacterial pathogen has killed oaks in woodlands throughout the Midlands and South but has not been recorded in other areas to date.

Tree professionals and conservation groups voiced concerns that if the disease got a foothold in the nation's woodlands then the landscape would be changed forever.

Tony Kirkham, responsible for the health of 14,000 tree at Kew, said: "Every year there is something new that will pose a threat to this amazing historical and new tree collection, and there is still a lot out there."

In the summer, the Forestry Commission warned that UK trees were facing an "unprecedented level of threat" from pests and diseases.

Hilary Allison, policy director for the Woodland Trust, said that it was important that research into all the threats to UK trees received the necessary funding.

"Ash dieback is now one more of a whole range of pests and diseases already present in the UK, all of which pose a threat to our native woods and trees," she said.

"All of our native trees are important for biodiversity, for providing habitats for our native wildlife - some species unique to particular types of tree - and for the health and wellbeing of our nation."

She told BBC News: "Another source of concern is that landowners worried about tree disease may perceive the risk of planting trees too great, actually leading to a reduction in tree planting and a decline in the UK's woodland overall.

"Given that the UK is already one of the least wooded countries in Europe, and what we know about the public's love of woodland and all the health and economic benefits associated with it, this would be a catastrophe for all concerned."

In order to carry out a "rapid survey" of how far ash dieback had spread, 500 Forestry Commission staff have been redeployed to examine 2,500 10km x 10km areas for signs of the disease.

Responding to concerns that other aspects of the Commission's work would suffer as a result, a Defra spokesman said: "Although this is challenging for the organisation, measures are being taken to minimise the impacts on customers and stakeholders.

"Most staff will return to normal duties within two weeks. However, a core staff team will be retained full time on Chalara disease research for as long as necessary."

The survey's findings will shape the government's response to the outbreak and what resources will be invested in tackling the disease.

But any effort to limit its spread will be a challenge, politically, ecologically and financially.

"If the reports are true that [ash dieback] spores can travel 20-30km in the air, then you are talking about removing all ash trees from that sort of area," Dr Kirby warned.

"I don't think that is going to be feasible. From experience of past diseases, I think we are going to find that it is probably already widely established.

"The general pattern in the past is that once we detect a disease, it has usually been around for a few years already.

"I fear that it is going to become part of the future pattern that we have got to deal with."

How ash dieback could threaten Britain's wildlife

Britain's population of 80 million ash trees provides shelter and food for a wide range of wildlife, mostly birds and insects. The species' loosely-branched structure means plenty of light reaches the woodland floor, allowing a variety of plants to grow beneath them.

Wild garlic (ramsons) is among the plants that thrives beneath the ash tree. Others include dog's mercury, wood cranesbill, wood avens and hazel. Because ash bark is alkaline, the trees also support a wide range of lichens and mosses and attract snails.

Carpets of bluebells are often seen under and around ash trees. Norfolk’s Lower Wood, in Ashwellthorpe, famous for its spring display of bluebells, is among those areas where ash dieback disease has been discovered.

A rich ground layer beneath the ash means plenty of food for birds such as warblers, flycatchers and redstarts. Hole-nesting birds, such as owls, woodpeckers and the nuthatch, are also frequent visitors.

More than 100 species of insect are also known to live on ash. At least 60 of the rarest have an association with the tree – mostly beetles and flies. Because ash is very long-lived, it can also support specialist deadwood species, like the lesser stag beetle.

The brown hairstreak butterfly, the largest of the UK hairstreaks, is also a frequent user of the ash. They congregate high in the trees for breeding. Ash also supports a wide variety of moths. Source: The Wildlife Trusts