Great whites 'not evolved from megashark'

- Published

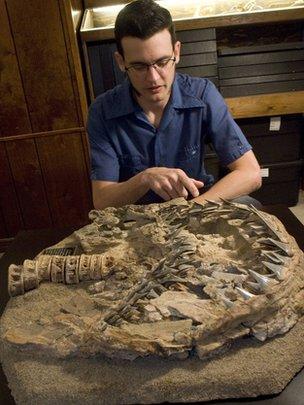

The new specimen (examined here by Dana Ehret) links Great Whites to the much smaller mako shark

A new fossil discovery has helped quell 150 years of debate over the origin of great white sharks.

Carcharodon hubbelli, which has been described by US scientists, shows intermediate features between the present-day predators and smaller, prehistoric mako sharks.

The find supports the theory that great white sharks did not evolve from huge megatooth sharks.

The research is published this week, external in the journal Palaeontology.

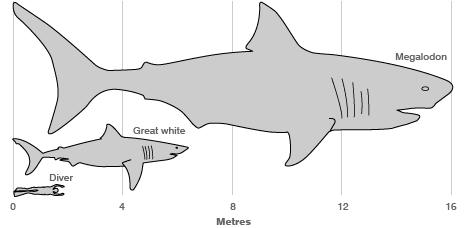

Palaeontologists have previously disagreed over the ancestry of the modern white sharks, with some claiming that they are descended from the giant megatooth sharks, such as Megalodon (Carcharocles megalodon).

"When the early palaeontologists put together dentitions of Megalodon and the other megatooth species, they used the modern white shark to put them together, so of course it's going to look like a white shark because that's what was used as a model," explained Professor Dana Ehret of Monmouth University in New Jersey who lead the new research.

Modern day white sharks show similarities in the structure of their teeth with the extinct megatooth sharks.

As they both sport serrations on the cutting edges, early scientists working on the animals used this as evidence for the sharks being closely related.

"But we actually see the evolution of serrations occurring many times in different lineages of sharks and if you look at the shape and size of the serrations in the two groups you see that they are actually very different from each other," Professor Ehret told BBC News.

Megalodon had one of the most formidable bites known from the fossil record

"White sharks have very large, coarse serrations whereas megalodon had very fine serrations."

Now, additional evidence from the newly described species shows both white shark-like teeth shape as well other features characteristic of broad-toothed mako sharks that feed on smaller fish rather than primarily seals and other large mammals.

"It looks like a gradation or a transition from broad-toothed makos to the modern white shark. It's a transitional species, and you don't see that a whole lot in the fossil record," Professor Ehret said.

The mako-like characteristics of the new species, named Carcharodon hubbelli in honour of Gordon Hubbell - the researcher who discovered it in the field - were only found due to the incredible preservation of the fossil.

"A big issue in shark palaeontology is that we tend to only have isolated teeth, and even when you find associated teeth very, very rarely are they articulated in a life position," continued Professor Ehret.

"The nice thing about this new species is that we have an articulated set of jaws which almost never happens and we could see that the third anterior tooth is curved out, just like in the tooth row of mako sharks today," he said.

David Ward, an associate researcher at the Natural History Museum, London, who was not involved in the study told BBC News: "Everyone working in the field will be absolutely delighted to see this relationship formalised."

The mosaic of both white shark-like and mako-like characters had been spotted by the researchers in an initial description of the fossil, external, but the age of the fossil meant their conclusion that the species was intermediate between a mako ancestor and modern white sharks wasn't fully accepted.

"Some folks said 'well, it makes a great story, but it's not old enough because by this time, the early Pliocene, we see full blown white sharks in the ocean.'"

This led Ehret and his team to revisit the original site the fossil was taken from the Pisco Formation in Peru to re-examine the geology of the area, guided by the original field notes of Gordon Hubbell.

"Gordon gave us two photographs from when he actually collected the specimen and then a hand drawn map with a little 'X' on it. We tried to use the map and we didn't have much luck.

"But using the two pictures of the excavation, my colleague Tom Devries was able to use the mountains in the background."

"We literally walked through the desert holding the pictures up, trying to compare them. That's how we found the site."

Not only did they find the site, but the team were able to discover the precise hole from which the fossil had been excavated in 1988, before making a lucky escape from the desert.

"We made it back to Lima with about three hours to spare before an earthquake hit and shut down the transcontinental highway for two weeks. It was quite a trip."

By analysing the species of molluscs found fossilised at the site, the team found that the shark was actually two million years older than had been thought, making it roughly 6.5 million years old.

"That two million year push-back is pretty significant because in the evolutionary history of white sharks, that puts the species in a more appropriate time category to be ancestral or... an intermediate form of white shark."

"We've bolstered the case that white sharks are just highly modified makos... It fits the story now," Professor Ehret told BBC News.

- Published5 May 2011