Governments 'too inefficient' for future Moon landings

- Published

Harrison Schmitt rushes across the lunar surface in search of important geological specimens. But just as the science got going the Apollo missions were scrapped.

One of the last men to set foot on the Moon has said that private enterprise will be the driving force for a return to the lunar surface.

Harrison Schmitt told the BBC that governments are "too inefficient" to send humans back to the Moon.

Mr Schmitt's comments come on the 40th anniversary of Nasa's last manned mission to the Moon, Apollo 17.

The veteran astronaut said that companies would soon embark on a new commercially driven space race.

Speaking to the BBC World Service's Discovery programme, he said that he felt that private firms could make a return on the huge investment needed to set up extra-terrestrial mining operations by garnering a new source of fuel called helium-3. The gas is similar to the helium used to blow up balloons, but has properties that some scientists believe make it the ideal fuel for nuclear fusion reactions.

"The economy of space and economy of settlements of the Moon will be supported by helium-3. When you have a reason to build rockets and spacecraft and mining machines, costs will come down," he told BBC News.

Mr Schmitt's comments come in the year that a group of billionaires, which include the film director James Cameron and Google's chief executive, Larry Page, unveiled plans to mine asteroids using robotic probes. It was also the year that Elon Musk's firm SpaceX successfully delivered cargo to the International Space Station using its Dragon freight capsule on top of a Falcon rocket. So could the private sector take the next giant leap for mankind and send people back to the Moon? Harrison Schmitt believes that there is no other way.

Highlights from the Apollo 17 mission

"Government is too inefficient to make the costs come down where it would be economic. It will be an entrepreneurial effort," he told the BBC.

Richard Nixon, the US President in 1972, had announced earlier that year that Apollo 17 would be the last mission to the Moon for the foreseeable future. Its launch on December 7 was a bittersweet moment for those involved in the US space programme and for all those who had followed their incredible exploits. Among those watching the launch was John Logsdon, now a professor at the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University.

Melancholy

"There was an undertone of melancholy. We had done those wonderful missions and that was the end of it."

The event was the first night launch of the powerful Saturn V rocket. For a moment night turned to day as the fire from its five F1 engines bathed the Kennedy Space Center with an incandescent glow. Then, as Apollo 17 surged upward like a fiery angel, darkness.

Back on Earth, the Watergate scandal had broken, President Nixon was making plans to begin a Christmas mass bombing campaign on the Vietnamese and the US was riven with conflict and protest.

Apollo 17 was perhaps the moment that marked the end of optimism.

The mission was the sixth to land on the Moon but arguably the first to devote a significant amount of time to scientific research. Harrison Schmitt was the first qualified geologist to be sent to explore the lunar surface.

Schmitt, along with fellow astronaut Eugene Cernan, spent three days on the Moon. They drove further on the lunar rover than anyone had driven before, collecting rocks and carrying out a series of experiments.

So at ease were the two men on the lunar surface they even found time for a song: "We were walking on the Moon one day," though this was quickly followed by a note of discord when the astronauts failed to agree whether the next line should be "...'merry, merry month of May'," as specified in the original song or the scientifically more accurate though less poetic "December".

Many felt that the Apollo missions had been scrapped just as they had got into gear. Nasa had plans for Apollo 18, 19 and 20 missions that would also be research intensive. But President Nixon took the decision to end this hugely successful programme because it had achieved its principal aim three years earlier when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon.

Very expensive

"There was no compelling reason to keep going with a very expensive programme," according to Prof Logsdon.

"We did it as a geopolitical act of competition with the Soviet Union to demonstrate the superior technological and organisational power of the US. It had very little to do with exploring."

Golden Spike Chairman Gerry Griffin: "The moon is of interest to the scientific community... and the commercial development of space"

Nasa's focus turned toward developing an orbiting laboratory, SkyLab, and the development of the space shuttle. The space agency believed that this was not the end of its glory years, rather the beginning of a new era where space travel would become cheaper and more commonplace.

Of course that never happened. Successive US Presidents have tried to match President Kennedy's inspirational challenge to Nasa and the nation more than 50 years ago:

"We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win."

Since then Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, both Presidents Bush and the current administration have matched neither their predecessor's rhetoric nor the financial support for such an endeavour. So the big question is whether anyone will ever set foot on the Moon again?

Prof Christopher Riley, a space historian at Lincoln University, is pessimistic.

"I suspect in my lifetime I have seen the last footprint on the Moon. It is very difficult for governments to do that kind of adventure at this time in the economic cycle."

It is a prospect that saddens Prof Riley. "One of the things that defines us as humans is this desire to explore and if we stop exploring we cease somehow a little bit to be human," he said.

International effort

First among the countries with the motivation and resources to send an astronaut to the Moon is China. It already has ambitious plans to send robotic explorers to the Moon next year. Those missions may prompt an Apollo-type effort by China to demonstrate its own technological power by sending an astronaut to the Moon.

Prof Logsdon believes that it would be far better for the next attempt at a Moonshot to be an international effort.

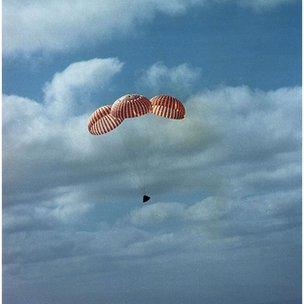

The last splashdown for Apollo. Will there ever be such a thrilling adventure again?

"One of the great political challenges of the next decade is whether China can be incorporated into the global space effort or whether because of a combination of its own intentions and the fact that they are not being welcomed - it puts them in a position where they choose to go it on their own."

For many who watched in awe as Nasa sent mission after mission to the Moon, a return to the lunar surface is not only possible but inevitable. It's a view that's implicit in the plaque left by the Apollo 17 astronauts which anticipates many more daring adventures.

"Here man completed his first exploration of the Moon - December 1972. May the spirit of peace in which we came be reflected in the lives of all mankind."

Discovery - Last Man, First Scientist on the Moon was first broadcast on BBC World Service on Monday 3rd December at 19:32 GMT, with repeats.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published24 April 2012

- Published31 May 2012