Fracking: Untangling fact from fiction

- Published

The Cuadrilla drilling operation at Westby in Lancashire

The government has announced that it will remove a temporary ban on hydraulic fracturing across the UK.

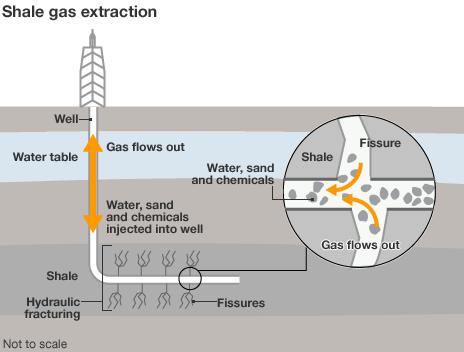

Fracking, as it is known, is a controversial technique for recovering gas and oil from shale rock. But how concerned should people be about the environmental impacts?

Hydraulic fracturing is widely used across the US to exploit reserves of oil and gas that were once believed to be inaccessible.

But in the UK, the use of fracking was halted in 2011 after some minor earthquakes near Blackpool, in north-west England, were attributed to test wells being drilled by the energy company Cuadrilla.

The company carried out its own report, external into the incident and found that it was "most likely" that the seismic events were caused by the direct injection of fluid into the fault zone.

The Department for Energy and Climate Change (Decc) then asked three experts to make an independent assessment. Their report indicated that future earthquakes as a result of fracking could not be ruled out - but the risk from these tremors was low and structural damage extremely unlikely. The experts also made recommendations on how to minimise these risks.

Another review, external, carried out by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering, also gave fracking the green light - provided that strong regulations were in place.

Earthquake issues have also been attributed, external to fracking in British Columbia, Canada, and in some parts of the United States.

But according to the Francis Egan, chief executive of Cuadrilla, there needs to be a sense of proportion about the risk of earthquakes from fracking.

"If you look at the British Geological Survey website, in the last two months alone there were nine events of the same magnitude," he told BBC News.

"We have a host of measures in place to ensure there is no recurrence."

It is expected that if fracking resumes in the UK, the government will insist on constant monitoring and a threshold of seismic activity.

If fracking causes a tremor above the limit, it could lead to a suspension of drilling.

Fluid situation

Many people have concerns about the fluid used in fracking. It is normally a mixture of water, sand and some chemicals that is pumped into the well under high pressure to force the gas from the rock.

There have been worries that the fluid is dangerous - suspicions that were fuelled by the reluctance of many companies in the US to disclose what's exactly in the mixture. Democrats in the US Congress released a report that detailed some 750 different chemicals and other components used in fracking fluid.

In the UK, Cuadrilla has been open about what is in its, external fracking mixture.

But the liquid going down into the well isn't the whole story.

Fracking requires tens of millions of litres of fluid - much of what goes down the well comes back up as "produced water".

It can contain a mixture of organic hydrocarbons, and naturally occurring radioactive material.

In the US, this water is often stored in open pits before it is processed but in the UK the pits will have to be covered.

Waste water from a fracking operation in Texas is stored in suface pits

In many locations where the facilities don't exist on site, the water has to be trucked away to be cleaned.

Prof Richard Davies, director of the Durham Energy Institute, external, says that this would also be the likely scenario in the UK if fracking becomes more widespread.

"It'll be a bit like Pennsylvania, where a whole industry has grown up to deal with waste-water," he said. "We'll have to clean the water if we want to re-use it."

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has suggested ways, external of cleaning up the water that is used in shale gas exploitation. The IEA says that the technologies to address these issues exist or are in development and if they are adopted, fracking might be more widely accepted.

The other water issue associated with fracking is the potential of the technology to contaminate existing drinking supplies. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) investigated complaints from residents in Pavillion, Wyoming, who complained that fracking was affecting their drinking water.

The EPA's initial report , externalconcluded that there was a link with the waste-water produced by drilling for gas. Further investigations into this incident haven't yet conclusively shown the sources of contamination.

There have been many other reports of a similar impact on drinking water from people living near fracking operations across the US.

Prof Davies says that when water has been contaminated in the US it has not been the fault of fracking. It has been as a result of cracks in the wells or surface spillages.

"We have been distracted by hydraulic fracturing," he told BBC News. "It is really at the bottom of the list when it comes to contaminating water supplies. Drilling wells properly and cementing them are the critical things."

In a report, external published in the journal Marine and Petroleum Geology, Prof Davies found that in the UK the possibility of fracking causing rogue fractures that would allow methane gas to contaminate water was a fraction of 1%.

The study recommended a minimum vertical separation distance between fracking wells and water supplies of 600m (2,000ft).

Some scientists have proposed adding chemical tracers to fracking fluids as a way of confirming that any contamination of drinking water comes from the drilling process.

Environmental disruption

Horizontal drilling can offer many advantages to the gas extraction process, allowing wells to be drilled in several directions from one pad. But there are downsides as well. Horizontal drilling means companies can extract oil and gas from locations that were once inaccessible, and these may be under built-up areas as they are in several cities in the US.

Sections of drill pipe are lined up to be used before fracking in Texas

The disruption that this can cause is considerable. Road traffic, drilling noise, and the danger of accidental fuel spillages are all associated with the process.

Mark Boling, executive vice president with Southwestern Energy, external, a US oil and gas exploration company that uses fracking technology, says the fracking industry needs to be more honest about the real impacts.

"We need to think more innovatively above the ground," he told BBC News. "We need to figure how to do better on surface impacts, water supply, water transfer and disposal, drilling locations - we really didn't come out and say, 'yes, these are risks, and there are obstacles'."

Mr Boling says that in many parts of the US, people have accepted the technology because they have seen a direct financial benefit from selling mineral rights. That's not something that pertains in the UK.

"You are going to have even more difficulty where the minerals are owned by the Crown - if you don't have something that is going to put money in the pockets of people that are suffering through all the trucks, road damage the compressor noise all these sorts of things."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external