Sharing: Chimp study reveals origins of human fair play

- Published

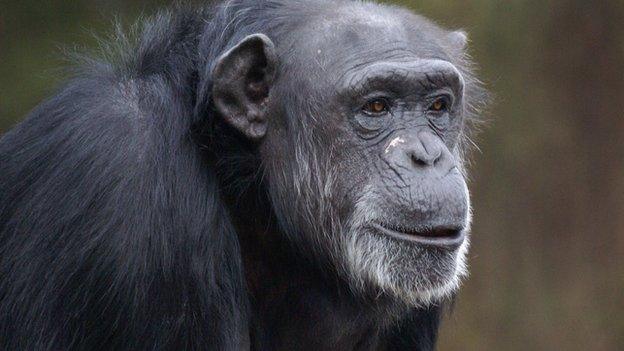

Sharing plays an important role in a co-operative chimp society

The human tendency to share may have more ancient evolutionary routes than previously thought.

This is according to a study of the performance of chimpanzees in a test called the "ultimatum game".

Traditionally, the game is employed as a test of economics; two people decide how to divide a sum of money.

This modified game, in which two chimps decided how to divide a portion of banana slices, seems to have revealed the primates' generous side.

Listen to Dr Darby Proctor explain the game the chimps played

The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external, was part of an effort to uncover the evolutionary routes of why we share, even when it does not make economic sense.

Scientists say this innate fairness is an important foundation of co-operative societies like ours.

The ultimatum game: When the first chimp takes a token and passes it to its partner, this represents an "offer"

Fair game

Lead researcher Darby Proctor from the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, external at Emory University, US, explained why she and her colleagues chose to use the ultimatum game, which has been used in the past to illustrate the human tendency to share.

During the game, one participant is given an amount of money and asked to "make an offer" to the second player. If that second player accepts the offer, the money is divided accordingly.

But, if the second player refuses that offer, both players receive nothing. This is the basis of the fairness versus economics quandary; if the first player proposes a selfish, unequal offer, the affronted recipient might refuse.

And this is exactly what happens in humans. Although it makes economic sense to give away as little as possible and accept any offer that's proposed, people usually make roughly equal, or "fair" offers, and tend to refuse unequal or "unfair" offers.

Dr Proctor and her colleagues trained their chimp participants to play a similar game, using coloured tokens to represent a reward.

"We tried to abstract it a little - to make it a bit like money," Dr Proctor explained.

"We trained them with two different tokens.

"If they took [a white token], they would be able to split the food equally, and taking the other [blue] token meant that the first chimp would get more food than the partner."

The researchers presented both tokens to the first chimp, which would then choose one and offer it to its partner.

As with the human version of the game, if the partner accepted the token, both animals received their reward.

Three pairs of chimps played this game, and the results revealed that the animals had a tendency to offer a fair and equal share of the food reward.

In another experiment, the team repeated the test with 20 children between the ages of two and seven. They discovered that both young children and chimps "responded like humans typically do" - tending to opt for an equal division of the prize.

"What we're trying to get at is the evolutionary route of why humans share," explained Dr Proctor.

"Both chimps and people are hugely cooperative; they engage in cooperative hunting, they share food, they care for each other's offspring.

"So it's likely that this [fairness] was needed in the evolution of cooperation.

"It seems to me that the human sense of fairness has been around in primates for at least as long as humans and chimps have been separated."

Dr Susanne Schultz from the University of Manchester said the study was very interesting and showed "the potential for chimps to be aware of fair offers".

"It is interesting that changing the study design - primarily by not using food rewards it seems - one can elicit fairness behaviour in chimps," she told the BBC.

She added though that is was not clear that the chimps completely understood the design of the game and that, with just six chimps involved in the study, further evidence would be needed to show clearly that chimps had a natural tendency towards fairness.

- Published1 September 2012