Landsat aims to maintain gold standard

- Published

- comments

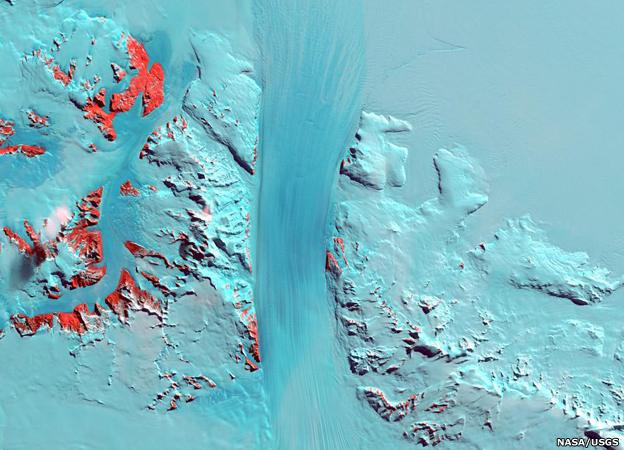

The Columbia Glacier descends the Chugach Mountains into Prince William Sound in Alaska. Landsat allows scientists to monitor the changing fronts of such ice streams

One of the very best ways to understand the changes taking place on Planet Earth is to make observations from space.

And to get a true sense of any trends, you really need those measurements to be long-term and unceasing.

Preferably, you use the same type of instrument to make the observations, and when, inevitably, you're required to replace aging equipment, you do so in such a way that the new system can be cross-calibrated with the old.

Few Earth observation programmes get as close to this gold standard as Landsat, the cooperative space mission run by US space agency (Nasa), external and the US Geological Survey, external.

For 40 years now, the Nasa/USGS satellites have maintained a permanent eye on Earth.

It was during the Apollo preparations - when astronauts would also take pictures of their home planet as they tested their Moon technologies - that the idea was born for a dedicated imaging system to observe the Earth.

It led to the development of the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS), launched on 23 July 1972 and operated for six years. Subsequent platforms picked up the baton. Today, Landsat-7 maintains the watch, with its successor, Landsat-8, being readied for lift-off next month.

The latest incarnation will go up from California's Vandenberg Air Force base on an Atlas rocket, and, after a few weeks of checks, assume the lead role of imaging the planet from an altitude of 705km.

The Landsat spacecraft view the Earth in visible and infrared wavelengths, and track details as small as 30m across.

It is not possible to see individual birds from space but we can recognise their habitats. The brown staining (centre) on the white ice is a consequence of guano, or penguin poo, dropped by a colony of emperors.

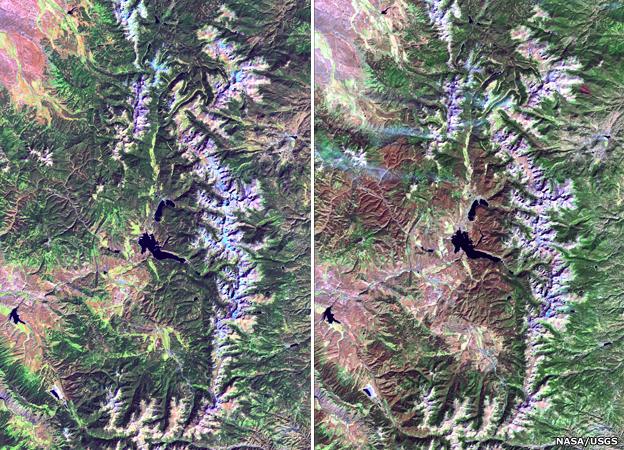

Insect damage: Two views of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado in 2003 (left) and 2010 (right). Spot the areas of tree death caused by the mountain pine beetle. The insect has been spreading its range to the north.

Water watch: The Aral Sea in central Asia was once the fourth largest lake in the world, but poor irrigation practice severely depleted its water reserves as seen in these Landsat images from 1977, 1989 and 2006.

Antarctica's Byrd Glacier: The satellite series has produced some of our best maps of the White Continent. We now have a complete pictorial view thanks to the Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica (LIMA) project.

Violent Earth: With a 16-day repeat to every place on the land surface, there is a good chance that a volcanic eruption will be recorded. This picture shows Mount Etna, Italy, blowing its top once again, this time in 2001.

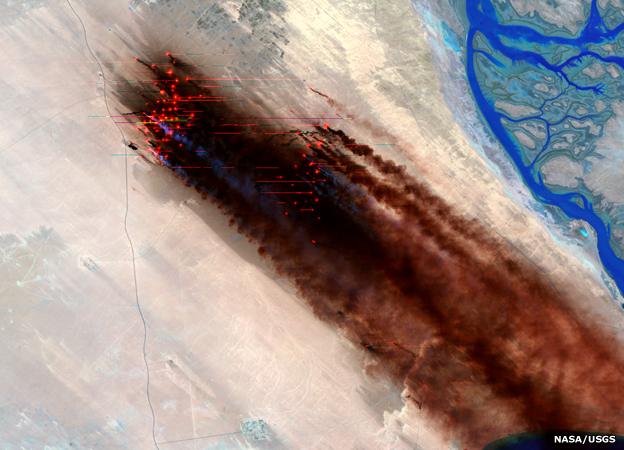

War scene: Landsat saw the devastating environmental fall-out from the end of the Gulf conflict in 1991 when retreating Iraqi forces set fire to Kuwaiti oil wells. The fires raged for months.

The meandering Mississippi River in all its glory. The blocks are towns, fields and pastures. Evident in this view are the countless oxbow lakes and cut-offs that trace the length of the North American river.

It's true there are imaging sensors up there now that will return pictures of Earth with far better resolutions (in the tens of centimetres), but for the job Landsat is trying to do, the 30m/pixel view is perfect.

Over its 40-year history, Landsat has catalogued the growth of the megacities, the spread of farming and the changing outlines of coasts, forests, deserts and glaciers. It has monitored fires and volcanic eruptions. It has even detailed the behaviours of Antarctic penguins and North American beetles.

"One [application] that we're particularly proud of is the use of something we call the thermal band," explained Matt Larsen, the associate director for climate and land-use change at the USGS.

"This is a technique by which we can estimate the temperature of the surface of the Earth from the sensors on the Landsat satellite, and from that we can measure evapotranspiration (the conversion of water to water vapour).

"Why do we care about that? That's a key part of agricultural activity, and in the western US where we have a huge amount of land in irrigated agriculture, it allows us to better understand how much water we are using, how much water we need and how that might be affected in the future because of changing stream flows because of changing temperatures," he told the BBC World Service's Science In Action programme (listen to our feature).

Landsat-8 will carry an additional thermal band that will lead to more precise measurements.

This Landsat-7 image from 1999 shows Eyjafjordur, a deep fjord on the northern coast of Iceland. Many have likened the shape of the coast and the colours used to render the image as looking like a tiger’s head

The uses of Landsat data really are innumerable.

Paul Donald, external, a conservation scientist with the UK's Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), gives a great example of how these pictures can be used to understand the geographical distribution of very poorly known avian species. You cannot see the birds from space, obviously, but you can map their likely habitat.

"One of the ways we can do this is to use a modelling technique, where we take Landsat data and we match that with areas where we know the birds are; and that will then give us a very good description of where the bird may be where people have never even been to look for it," he told us.

"The results have been extraordinary. We've generated maps using Landsat imagery which have predicted areas we never thought suitable for this bird. We've gone there, and we've found the bird."

Landsat-8 is more formally called the Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LDCM), external. This mouthful reflects the rather tortured route the mission had to take to get budget approval. It's a perennial problem for Earth observation missions - getting a timely sign-off from the politicians so that an enduring presence in orbit can be maintained. Even with Landsat, it is as if each satellite was born an only child, and the next mission had to fight for justification as if there had been no heritage.

Nasa, USGS and the Federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) are now seeking a long-term solution that would see Landsat-9 and all following spacecraft arrive on a predictable track.

It is the sort of assurance Earth observation seeks in Europe, also. At the end of this year, the European Space Agency will start to roll out the multi-billion-euro Sentinel fleet of satellites, which aim to echo the Landsat philosophy but with many more types of sensor. However, even as the first mission is prepared for launch, politicians are still arguing over how the project should be funded.

Ready to go: Landsat-8 will launch in February from California on an Atlas rocket