Europe gives 2bn euros to science

- Published

- comments

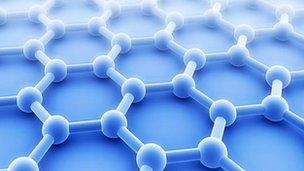

The project on graphene is one of two recipients of funding from the European Commission

Research projects investigating the "miracle material" graphene and the human brain have won unprecedented funding of up to 1bn euros each.

Under the European Commission's Future and Emerging Technologies programme, the backing is designed to give Europe an edge in key areas of research.

Graphene - a single-layer of carbon atoms - has extraordinary properties which give it immense potential.

Possible applications include flexible electronics and lighter aircraft.

The Human Brain Project will attempt to build a computer-based copy of a human brain to understand neurological disorders and the effects of drugs.

Both projects involve researchers in dozens of institutes across Europe and will receive the funding over a ten-year period. They include the scientists who first developed graphene at the University of Manchester, UK.

The two fields of novel materials and brain research are described as fulfilling the criteria for the funding by being "ambitious and risky" while promising large returns.

The backing is meant to answer the criticism that Europe lags behind more dynamic competitors such as the United States and China in economic growth and scientific research.

By focusing the funding on two key areas, the hope is that a "critical mass" can be achieved which will give Europe an edge in technologies vital to future economic development.

Patent race

Last month the BBC reported on the race to secure patents on graphene and how, despite the UK's early lead, China was now leading the field with the South Korean electronics giant Samsung holding nearly ten times more patents than Britain as a whole.

Graphene is far stronger than steel, more conductive than copper and more flexible than rubber so it could potentially open up entirely new avenues for manufacturing, consumer products and medical devices.

The material, so thin it effectively has just two dimensions, was first isolated by two Russian-born scientists, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, at the University of Manchester, work that earned them a Nobel Prize and knighthoods.

The European Commission vice-president Neelie Kroes, announcing the funding in Brussels today, said that it "rewards homegrown scientific breakthroughs".

"So, you've heard of Silicon Valley," she said.

"Where in Europe wants to be known as 'Graphene Valley'? That's the billion-euro question I am putting to you today."

The graphene funding will be spread across 126 academic and industrial research groups. It will be coordinated by Professor Jari Kinaret of Chalmers University of Technology at Gothenburg in Sweden who has stressed that it not attempt to match competitors in all areas.

"For example, we don't intend to compete with Korea on graphene screens," he said, a reference to Samsung's determined effort to lead the market in flexible electronic screens and e-paper. However graphene production - still not achieved on an affordable and industrial scale - is in the project's sights.

Profs Geim and Novoselov will play a leading role in guiding the collaborative effort.

Think big

Meanwhile the Human Brain Project will attempt to simulate the trillions of neural connections that make up a human brain in an effort to comprehend how the organ functions.

With an ageing European population, brain disorders, while becoming a more important feature of healthcare, remain poorly understood.

The Commission explains that the Human Brain Project will "collect the masses of clinical data available, mining for biological patterns, leading to new ways of diagnosing and classifying brain diseases."

The sheer volume of data involved in modelling the brain will itself lead to "radically new" IT with new computer technologies designed to manage the flow.

A further angle will be to explore how the brain manages such an intense workload with a relatively tiny power supply - "no more power than a light bulb". Understanding this could lead, it's hoped, to an entirely new way of powering energy-hungry supercomputer systems.

At a time of austerity across Europe and criticism of the European Commission's own budget, officials are emphasising the potential value of the funding for nurturing the kind of research that can produce an economic spin-off.

A key test will be how effectively the initial grants of 54m euros are handled. Beyond that, the precise level of future funding, which is meant to include contributions from industry, is still being negotiated.

Follow David on Twitter, external.

- Published15 January 2013