Last-stand Neanderthals queried

- Published

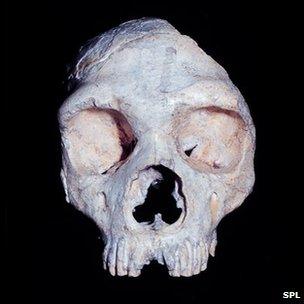

DNA studies confirm there was some mixing between Neanderthals and modern humans

We may need to look again at the idea that a late Neanderthal population existed in southern Spain as recently as 35,000 years ago, a study suggests.

Scientists using a "more reliable" form of radiocarbon dating have re-assessed fossils from the region and found them to be far older than anyone thought.

The work appears in the journal PNAS.

Its results have implications for when and where we - modern humans - might have co-existed with our evolutionary "cousins", the Neanderthals.

"The picture emerging is of an overlapping period [in Europe] that could be of the order of perhaps 3,000-4,000 years - a period over which we have a mosaic of modern humans being present and then Neanderthals slowly ebbing away, and finally becoming extinct," explained co-author Prof Thomas Higham from the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at the University of Oxford, UK.

"What our research contributes is that in southern Spain, Neanderthals don't hang on for another 4,000 years compared with the rest of Europe. And the hunch must be that they go extinct in the south of Spain at the same time as everywhere else," he told BBC News.

But one proponent of the recent survival idea said the work could not resolve whether the region acted as a refuge for the last populations.

Rock refuge

The length of time modern humans (Homo sapiens) and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) overlapped in Europe has been a keenly debated topic in recent times.

A long overlap raises important questions about the extent to which we might have interbred with them, and possibly even contributed to their eventual demise.

Successful re-dating was conducted on specimens from the Jarama VI cave site

Research published in 2011 indicated modern humans were living in the lands now known as Italy and the UK as far back as 41,000-45,000 years ago.

This may have put them in contact with European Neanderthals who, according to previous dating studies, persisted on the continent for many millennia after these dates.

On the Rock of Gibraltar, for example, it has been suggested that Neanderthals could possibly have hung around until as recently as 28,000 years ago before finally dying out.

But the new Oxford study finds such a timeline, and especially the notion of an Iberian refugium, to be problematic.

The research team screened more than 200 fossil bones from 11 Iberian Palaeolithic sites, looking for traces of collagen.

This major structural protein in bone is the most suitable target for radiocarbon dating, but the PNAS authors could only identify 27 specimens out of the haul that met the necessary standard. And of these, only six would yield a useable date.

Sample 'cleaning'

A technique known "ultrafiltration" was deployed in the analysis. This is a method for "washing out" modern carbon contaminants in specimens prior to the dating process.

"Ultrafiltration removes smaller degraded fragments of proteins and other molecules such as amino acids, allowing us to date the large collagen strands that are nice and intact," said study leader Dr Rachel Wood, currently affiliated to the Australian National University, Canberra.

"It gives us more confidence that the dates are accurate."

A Neanderthal jaw from Zafarraya: Most specimens produced no useable collagen for testing

The six successful measurements did not involve Neanderthal bone but rather animal remains found in sediment layers associated with Neanderthals.

The two sites were Jarama VI, a rock shelter not far from Madrid in central Spain, and Zafarraya, another cave, near Malaga on the southern Spanish coast.

Neanderthal occupations at both these locations had previously been dated to about 35,000 old. However, the new Oxford assessment found them to be closer to 50,000 years old.

But Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum, who was not involved with the latest study, said: "Radiocarbon methodology on bone will not resolve the question of the last Neanderthals.

"What they have done is look at two sites in Iberia where - using my own models - I would never have predicted a late Neanderthal extinction. One is up in the high Meseta of central Spain, at 1,000m or more, with a very harsh climate and the other is in the mountains of Granada - again in a very harsh environment.

"These climates are so cold and dry, that is where the collagen in the bone has preserved and they have been able to get dates... What I think the method is giving us is a skew, a bias, towards older dates by the very nature of the preservation."

Gene evidence

Though once thought to have been our ancestors, the Neanderthals are now considered an evolutionary dead end.

They first appear in the fossil record hundreds of thousand of years ago and, at their peak, dominated a wide range, spanning Britain and Iberia in the west to Israel in the south and Uzbekistan in the east. Our own species, Homo sapiens, evolved in Africa, and displaced the Neanderthals after entering Europe somewhere around the 45,000-year mark.

No-one can say for sure what, if any, active role modern humans had in the decline of Europe's Neanderthals.

What is clear though is that some mixing must have occurred somewhere at some point. This is evident from DNA studies that prove Neanderthals made a small but significant contribution to the genetics of many modern humans.

However, scientists think this interbreeding could have occurred outside Europe, in the eastern Mediterranean or Middle East region (the area archaeologists call the "Levant"), and quite probably even deeper in time - some 80,000-90,000 years or so ago.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published23 October 2012

- Published2 November 2011