Ice blades threaten Europa landing

- Published

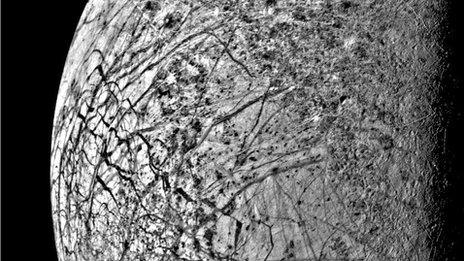

Jagged blades of ice may cover the equatorial area of Europa

Jupiter's icy moon Europa is a prime target for future space missions as it harbours a buried ocean that could have the right conditions for life.

But attempts to land may face a major hazard: jagged "blades" of ice up to 10m long.

A major US conference has heard the moon may have ideal conditions for icy spikes called "penitentes" to form.

Scientists would like to send a lander down to sample surface regions where water wells up through the icy crust.

These areas could allow a robotic probe to sample a proxy for ocean water that lies several kilometres deep.

Details of the penitentes theory were announced as scientists outlined another proposal to explore the jovian moon with robotic spacecraft.

On Earth, these features (so named because of their resemblance to the pointed caps worn by "penitents" in Easter processions around the Spanish-speaking world) form in high altitude regions such as the Andes.

Here, the air is both cold and dry, allowing ice to sublimate (turn from a solid into vapour without passing through a liquid phase).

Penitentes begin to form when irregularities in the surface of the snow are enhanced by the Sun's energy. These furrows then act as a trap for solar radiation, and, as they deepen, the tall peaks are left behind.

Sun overhead

Dr Daniel Hobley, from the University of Colorado, who presented his research at the 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, external in Texas on Tuesday, said the formation of penitentes also required the Sun to be overhead as much as possible.

"Light coming in at a high angle will illuminate the sides of the blades, causing them to retreat away," he explained.

On Earth, this restricts them to between 30 degrees latitude from the equator.

"Europa is very strongly tidally locked to Jupiter and Jupiter is very strongly tidally locked to the plane of the Sun. So the Sun is always coming down straight from above on Europa," said Dr Hobley, so the moon fulfils this requirement nicely.

He added: "You need a strong thermal gradient between the spike at the top of the penitente and the pit at the bottom. So any mechanism that acts to suppress that, i.e. warm cloudy days - or hot air - will also kill them."

With its negligible atmosphere, this wouldn't be a problem on Europa, suggesting the moon could have more or less ideal conditions for the formation of these icy blades.

"From our point of view, if the surface of Europa is subliming - if it is being sculpted by the sunlight - it will form these features," Dr Hobley told BBC News.

"The question then becomes: can it sublime the ice to produce these features faster than other processes that might erode the surface."

Using the angle of the Sun, the team was able to estimate temperatures on Europa's surface. This in turn allowed them to calculate that penitentes are probably restricted to between 15 and 20 degrees latitude from the equator. They also estimate that the penitentes within this region are likely to be between 1m and 10m in depth.

Outside this region of latitude, other erosional processes can outcompete penitente formation. These include "sputtering" erosion - the bombardment of the surface by very fast charged particles (a process similar to sandblasting) - and impacts by meteorites.

But Dr Hobley added: "We are expecting a band around the equator where it is… spiky."

There is a limit to the lifetime of these features: Europa's surface is relatively young, having been resurfaced by currently unknown processes some 50 million years ago.

"If we're on crust that's about 50 million years old and we're near the equator within the plus minus 20 degree latitude band, we're expecting to get 5m deep, spiky things that you really wouldn't want to send a lander onto."

Regions of the icy crust may also "wander" from their original location. This could transport penitentes beyond the ideal latitude band, but may also limit their formation.

Potential problem

Dr Javier Corripio, a glaciologist who has studied the formations in the Andes, said Dr Hobley had come up with an "interesting hypothesis".

However, he highlighted a potential problem. During the formation of penitentes, the furrows deepen such that they are sufficiently sheltered from the wind for melting to occur - which helps further deepen the depressions.

Dr Corripio told BBC News: "I have always seen some melting at the bottom of the penitentes, and never found them in very cold snowpacks, which is the case on Europa."

He suggested that another process could be active on Europa's surface: "Since temperature and atmospheric pressure are very low, sublimation rates are also very low. Then, vapour may simply migrate from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure, causing a very slow growth of snow crystals."

But he added: "In any case, it is a situation worth considering for future missions to that moon."

Indeed, Dr Hobley may have a way of testing the idea. Because of the way the Sun moves across the sky, penitentes should be oriented in an east-west direction. This might be visible as a polarisation in measurements of the surface.

Dr Hobley pointed out that there was a band around the moon's equator that is "anomalously cold", which means that it holds on to heat better than other regions of the surface.

Penitentes may or may not provide an explanation, but heat would tend to bounce around the blades rather than being fired back out.

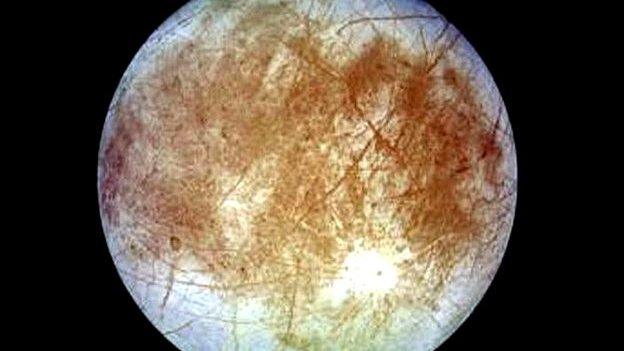

In the near-term, scientists would like to send a lander to the surface to "taste" the ice in regions where liquid water surges up to Europa's surface from the vast ocean beneath. A study released this month found further, strong evidence that salty water makes its way out to Europa's frozen exterior.

Co-author Mike Brown from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) said: "We now have evidence that Europa's ocean is not isolated - that the ocean and the surface talk to each other and exchange chemicals."

He added: "If you'd like to know what's in the ocean, you can just go to the surface and scrape some off."

Nasa had planned an orbiter mission with Europe's space agency, called the Europa-Jupiter System Mission, external (EJSM) to have launched in 2020. But the project was abandoned because of budgetary concerns.

At the LPSC, US researchers associated with the EJSM outlined details for another proposal to explore the jovian moon. Europe also hopes to salvage something from the EJSM work through a mission called Juice.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published16 November 2011

- Published16 November 2011

- Published16 February 2013

- Published28 January 2013