Q&A: Asteroid and comet impacts

- Published

Much of the impact was felt in the city of Chelyabinsk, in central Russia

On Friday, a meteor plunging towards Earth reportedly injured hundreds of people, as the shockwave blew out windows and rocked buildings. Later on Friday, the asteroid 2012 DA14 will make a close pass of Earth, skimming by at a distance of 28,000km.

Astronomers have ruled out any chance of a collision between that asteroid and Earth. But the two unconnected events highlight the potential danger from the primordial material that orbits in our cosmic neighbourhood. So what threat is posed to Earth by all the other cosmic debris out there?

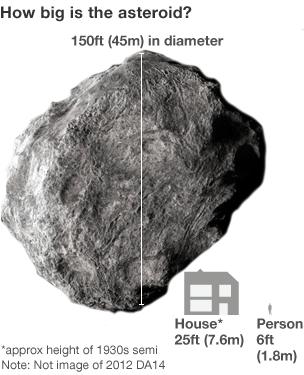

There's no danger from 2012 DA14, but what would happen if a similar-sized rock were to hit us?

We don't know for sure what 2012 DA14 is made of. But asteroids measuring less than 100m across - and made of stony material - are liable to break up high in the atmosphere.

Declassified data from US military satellites (designed to monitor nuclear weapons tests) show that many such rocks burn up with no ill effects on the ground.

But occasionally, one of these "airbursts" can occur close enough to the Earth's surface to cause serious damage.

In 1908, an asteroid or comet measuring tens of metres across detonated about 10km above Siberia. The explosion flattened some 80 million trees over an area of 2,000 sq km (800 sq m) near the Tunguska River - as luck would have it, a sparsely populated region.

One theory proposes that the Tunguska object was a fragment of Comet Encke. This ball of ice and dust is responsible for a meteor shower called the Beta Taurids, which cascade into Earth's atmosphere in late June and July - the time of the Tunguska event.

If an equivalent event had occurred over London, it would have destroyed everything within the bounds of the M25 motorway. So media reports of 2012 DA14 as an asteroid big enough to level a city are not so wide of the mark.

An object of similar size to 2012 DA14 carved out the magnificent 1.2km-wide depression known as Meteor Crater in Arizona. This object was metallic - composed of iron and nickel - ensuring that it reached the ground relatively intact.

Early reports suggest the one that soared across Chelyabinsk in Russia on Friday weighed about 10 tonnes. There was no estimate for its diameter, but it was probably smaller than any of these objects.

These things are just big chunks of rock or metal - how can they have such devastating effects?

The small rocks, or meteoroids, that shower our planet all the time are travelling very fast, perhaps as much as tens of kilometres per second. As already mentioned, most simply burn up in the atmosphere, while the smaller number that survive the plunge to the surface have their velocities slowed drastically by atmospheric friction.

For those heavier than a few hundred tonnes, however, atmospheric friction has little effect on their velocities. A rock with that kind of mass travelling at high velocity will release a huge amount of energy when it smacks into the Earth's surface.

Jodrell Bank's Tim O'Brien on when and where to see the asteroid in the UK

This is because the kinetic energy of the space rock is the product of half the mass and the square of the velocity. In other words, if you double the speed of the object, its kinetic energy will go up by a factor of four.

Though there are other factors which determine the effects of a given asteroid impact, such as the angle of entry and the nature of the target geology, it is not difficult to see why the energy released explosively by the larger classes of space rock can be many times that of a nuclear weapon.

In fact, researchers at Purdue University in the US and Imperial College London have put together a website, external called Impact Earth! that allows users to input the parameters of the asteroid and find out what effects if would have if it were to hit Earth.

How big can they get?

The asteroid whizzing by our planet on Friday is actually dwarfed by some of the debris out there.

The impact implicated in killing off the dinosaurs 65 million years ago was probably caused by an object some 10-15km wide.

The space rock hurtled through our atmosphere, striking Mexico's Yucatan peninsula. Scientists estimate that the explosive energy released by the impact was equivalent to 100 trillion tonnes of TNT - billions of times more explosive than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The huge crater that remains from the event is some 180km in diameter and surrounded by a circular fault about 240km in diameter.

While rocks the size of 2012 DA14 can potentially have devastating effects on a regional scale, the aftermath of the Cretaceous impact was global and long-lasting.

Initially, the Chicxulub impact triggered large-scale fires, huge earthquakes, and continental landslides which generated tsunamis. Then the hot rock and gas blasted at high velocity into the atmosphere shrouded the planet in darkness. There is evidence for considerable cooling following the asteroid strike; this "impact winter" could have lasted up to 10 years.

An object of this size hitting Earth today could potentially wipe out civilisation.

Statistically, rocky or iron asteroids larger than about 50m would be expected to hit Earth about every century. Asteroids larger than a kilometre are likely to collide with our planet every few hundred thousand years.

How much do we know about what's out there?

There are a number of search networks around the world set up to catalogue the potentially threatening objects in our neighbourhood. One of them is the US space agency's Near Earth Objects (Neo) programme, which manages and funds the search, study and monitoring of asteroids and comets whose orbits periodically bring them close to the Earth.

In 1998, Nasa started compiling an inventory of space rocks larger than one kilometre (0.62 miles) in diameter. But in 2005, the agency was set the much more challenging task of logging objects as small as 140m (460ft) in diameter. The target is to find 90% of them by 2020.

But the close flyby of 2012 DA14, the meteor strike in Russia and the forthcoming approach in November by Comet Ison (unknown before last year) show that there are vast gaps in our knowledge. This issue is dealt with in more detail here.

What can we do if astronomers detect something with our name on it?

One of the best known strategies for dealing with an incoming asteroid - applied by Bruce Willis in the film Armageddon - is to detonate a nuclear weapon near the surface of the object or below it.

The hope is that, in addition to blasting a large chunk out of the object, the explosion would nudge the asteroid off a collision course with Earth. However, if we were unlucky, this could fragment the space rock, potentially sending multiple chunks heading towards our planet.

Another strategy is to slam a spacecraft into the object to knock it off course. The European Space Agency (Esa) has designed a mission called Don Quijote, which will study the effects of just such a collision in space.

With a longer lead time, a spacecraft could be sent to intercept a space rock and fire its engines to slowly push the object off its current trajectory. Firing lasers at the surface of the asteroid might also be a way to deflect the rock.

Another, more surprising idea, is to fire balls of light-coloured paint at the object to increase its reflectivity. The pressure of light particles bouncing off the reflective coating, acting over time, would divert the rock off its path.

However, there is no firm timetable either for Don Quijote or other missions to test strategies for asteroid deflection.

How do I see the 2012 DA14 flyby?

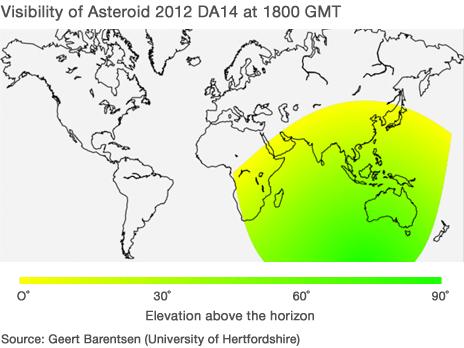

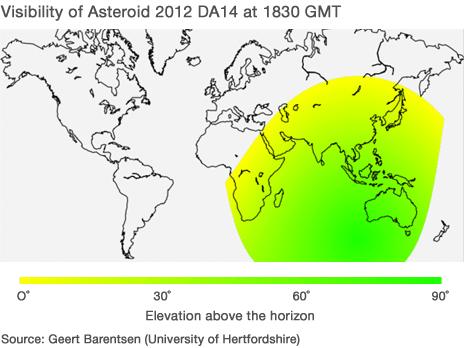

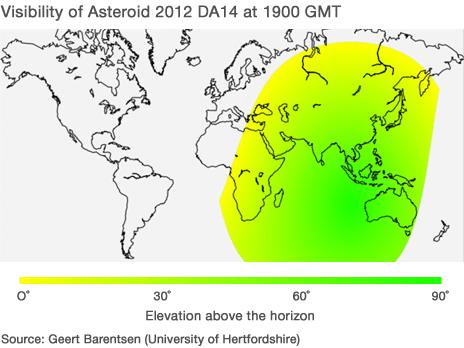

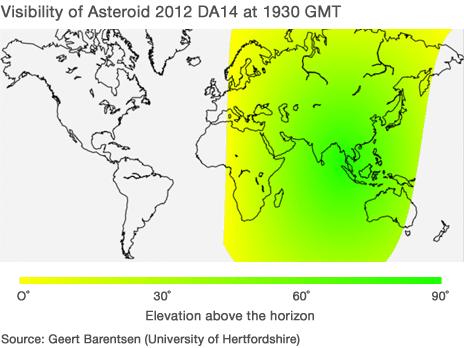

The 45m-wide asteroid is not quite bright enough to be visible with the naked eye, but it can be observed through good binoculars between 1800 and 2200 GMT. It is best viewed from Europe, Australia and Asia, but will be whizzing by fast.

Astronomer and journalist Stuart Clark says, external it will be "crossing an area of the sky as wide as the full moon roughly every 30 seconds".

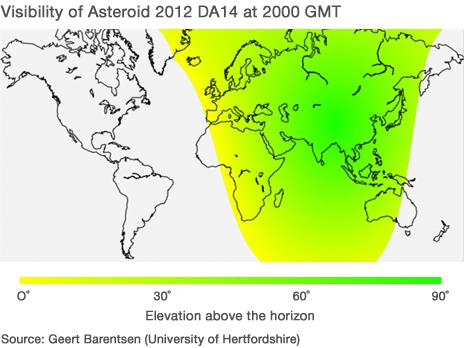

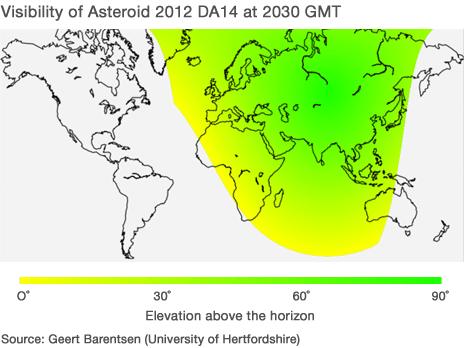

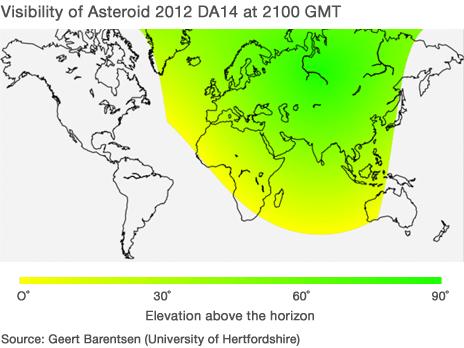

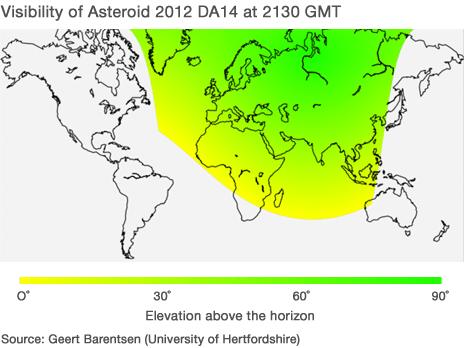

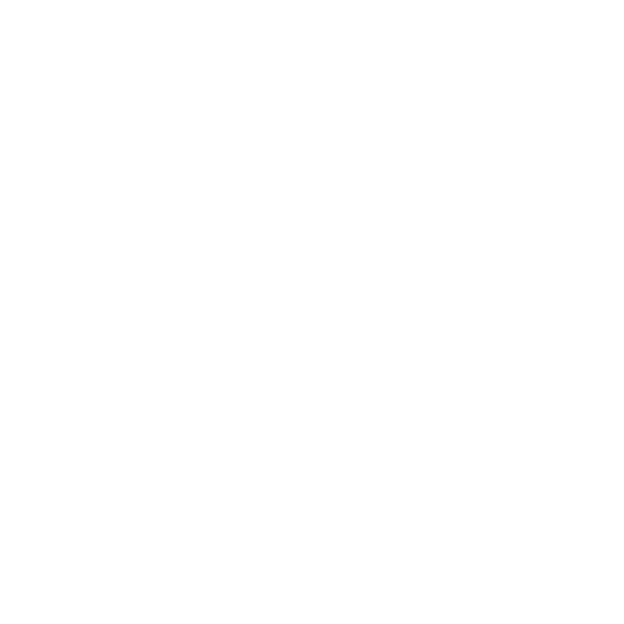

The asteroid will only be visible from some regions on Earth. Click through these maps produced by Dr Geert Barentsen, of the University of Hertfordshire, to see when the asteroid should be visible in different areas:

For skywatchers in the UK, the graphic below indicates roughly where in the northern sky to try to spot 2012 DA14.

- Published15 February 2013

- Published15 February 2013