Scans reveal intricate brain wiring

- Published

The BBC's Pallab Ghosh gets a look at how his brain is wired

Scientists are set to release the first batch of data from a project designed to create the first map of the human brain.

The project could help shed light on why some people are naturally scientific, musical or artistic.

Some of the first images were shown at the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Boston, external.

I found out how researchers are developing new brain imaging techniques for the project by having my own brain scanned.

Scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital are pushing brain imaging to its limit using a purpose built scanner. It is one of the most powerful scanners in the world.

The scanner's magnets need 22MW of electricity - enough to power a nuclear submarine.

The researchers invited me to have my brain scanned. I was asked if I wanted "the 10-minute job or the 45-minute 'full monty'" which would give one of the most detailed scans of the brain ever carried out. Only 50 such scans have ever been done.

I went for the full monty.

It was a pleasant experience enclosed in the scanner's vast twin magnets. Powerful and rapidly changing magnetic fields were looking to see tiny particles of water travelling along the larger nerve fibres.

By following the droplets, the scientists in the adjoining cubicle are able to trace the major connections within my brain.

Arcs of understanding

The result was a 3D computer image that revealed the important pathways of my brain in vivid colour. One of the lead researchers, Professor Van Wedeen, gave me a guided tour of the inside of my head.

He showed me the connection that helped me to see and another one that helped me understand speech. There were twin arcs that processed my emotions and a bundle that connected the left and right sides of my brain.

Prof Wedeen used visualisation software that enabled him to fly around and through these pathways - even to zoom in to see intricate details.

He and his team hope to learn how the human mind works and what happens when it goes wrong

"We have all these mental health problems and our method for understanding them has really not changed for over a hundred years," he said.

"We don't have imaging methods as we do for the heart to tell what's really going on. Wouldn't it be fantastic if we could get in there and see these things and give people advice concerning what their risks are and how we could help them overcome those problems?"

The brain imaging technology is being developed for a US-led effort to map the human brain called the Human Connectome Project, external.

And just as with the Human Genome Project before it, the data will be publicly released to scientists as the scans are processed, with the first tranche of data from between 80 and a 100 people to be released in a few weeks' time.

The HCP is a five-year project funded by the National Institutes of Health. The aim the $40m programme is to map the entire human neural wiring system by scanning the brains of 1,200 Americans.

Researchers will also collect genetic and behavioural data from the subjects in order to build up a complete picture of the factors that influence the human psyche.

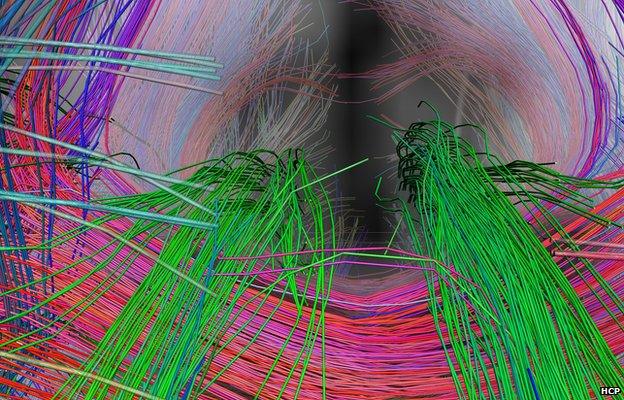

A close-up view of the centre of the brain looking back. The large green paths are the “cingulum” bundles, and connect areas of the frontal lobes that serve executive function with the hippocampus, which is the centre of memory. The large red bundle going left to right is a part of the corpus callosum, a huge bundle that connects the left and right sides of the brain.

This is a wider view of the previous image, showing a complete cross-section through the front of the brain, with cingulum bundles at the centre. A reduction in the number of fibres in the cingulum bundle is being studied as a possible early marker for Alzheimer’s disease.

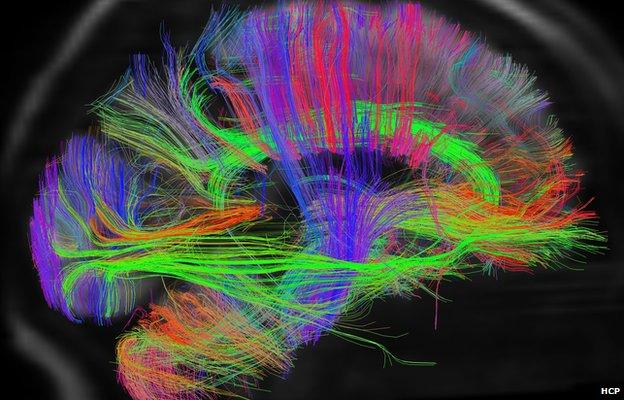

A side view of brain pathways, from the right. At far left is the visual cortex, connected by a large bundle, green, which connects to the frontal lobes. At centre, the vertical pathways in blue serve voluntary movement, connecting the motor areas of the brain with the spinal cord and muscles. The green path at centre is the right cingulum bundle, here seen from the side. The cerebellum, which controls coordinated movement, can be seen at bottom left.

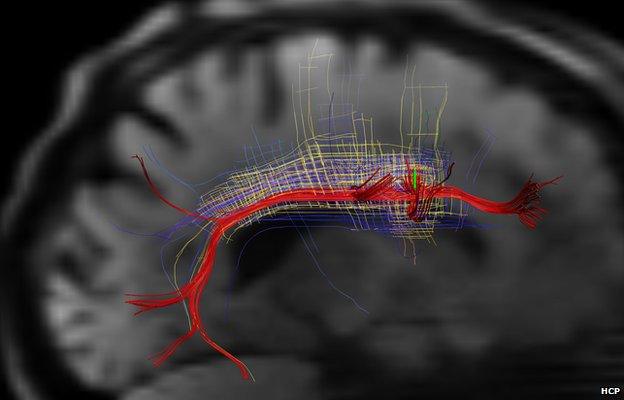

This is the language pathway of the brain and its organisation as part of a regular grid of pathways. In this view of the left hemisphere, the major pathway of language has been selected. The “arcuate bundle” is coloured red, and beside it are families of adjacent pathways that together make up a single connected grid. Recent data suggests this motif is widespread, and may reflect a basic organising principle of brain architecture. Changes in the organisation of this language pathway have been associated with dyslexia and related learning disabilities.

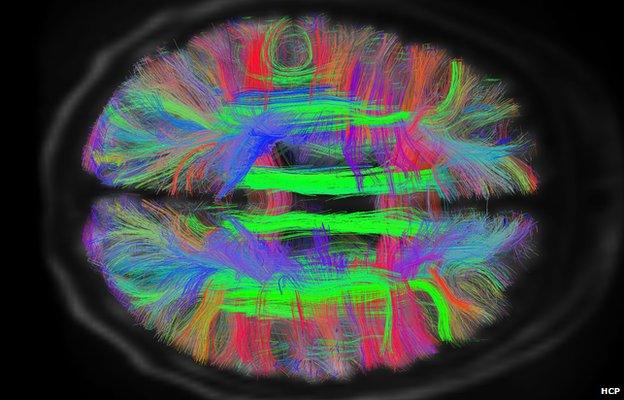

The brain pathways as seen from above. Here, the two green paths near centre are the cingulum bundles, and the two C-shaped green paths closer to the sides are major pathways of language, the arcuate bundles. These paths connect the frontal lobes, where facial movements are controlled, with the temporal lobes below, where sounds are processed, hearing interpreted, and utterances planned.

The brain's wiring diagram is not like that of an electronic device which is fixed. It is thought that changes occur after each experience, and so each person's brain map is different - an ever changing record of who we are and what we have done.

The HCP will be able to test the hypothesis that minds differ as connectomes differ, according to Dr Tim Behrens of Oxford University, UK.

"We're likely to learn a lot about human behaviour," he told BBC News.

"Some of the connections between different parts of the brain might be different for people with different characters and abilities, so for example there's one connection we already know about in people who like taking risks and (a different one) for people who like playing it safe.

"So we'll be able to tell the type of people who like skydiving and who would rather watch TV from their brain scans.

"It will be an amazing resource for the neuroscience community to help them in their work to understand how the brain works," he said.

Prof Steve Petersen, who works with the HCP at Washington University in St Louis, wants to identify the different parts of the brain involved with our ability to think about scientific problems, to concentrate and to hold information in our memory.

"The romance to me is that we are getting to our humanity," he said.

- Published5 September 2012

- Published2 February 2012

- Published15 November 2011