Wildlife conservation - Gangnam style!

- Published

- comments

Feeding time at the world's biggest crocodile farm near Bangkok

The man with the megaphone looked, in the words of one delegate, a little bit like Korea's much lamented Kim Jong-il.

Uthen Youngprapakorn is Thai, not Korean, but he does share some of the revolutionary fervour that marked out the late "dear leader".

He runs the world's biggest crocodile farm, located just outside Bangkok. And a couple of days ago, he played host to a visiting party of delegates to the Cites conference taking place in the city.

Crocodiles are everywhere you look - young ones, old ones, big ones, mean ones. Uthen's crocs simply rock.

Each year, he kills 100,000 for shoes, bags and food. Each year, three million people pay to see his collection.

This allows him to work on rare breeds of endangered crocodiles.

As he shows the delegates round, he proudly displays a basketful of baby crocs, six months old and, quite literally, snap happy.

These are the rare Tomistoma crocodile, or the false gharial, an endangered freshwater species. Uthen says he has now managed to breed 800 of them.

This makes quite an impression on the visitors. But not as much as Uthen's next trick.

For not only does his farm have crocodiles, he has a vast collection of other species, including performing elephants.

And as the attendees from the Convention on Trade In Endangered Species sit in a little stadium, we are treated to an elephant exhibition of painting.

Then four of Uthen's elephants start to dance - Gangnam style.

Oh yes. The large pachyderms gyrate to the tinny music, crossing their front legs, again and again in unison, a la Psy.

Around three million visitors a year come to this zoo, but some of the sights are distressing

Several of the delegates recoiled in horror. But one or two others heeded Uthen's megaphoned exhortations and joined in.

I sat transfixed. I asked Uthen later if it was cruel to have elephants prancing around, mimicking humans.

He didn't see it that way. "What happens if you just let the elephants walk? They have no exercise. Why are our elephants not so fat and not so skinny? Because we let them out dancing every day, then they burn the energy; they eat and burn, eat and burn," he said.

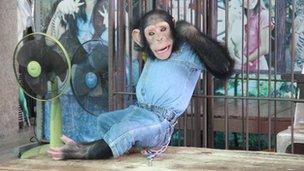

But it wasn't just elephants. There were monkeys in jeans, tiger cubs in cages, and crocodile wrestling, several times a day.

Many people might dismiss this as some sort of freak show but among the delegates on this visit, there were open minds.

For Cites, above all else, is about trade. It is not about tree-huggers or animal rights; it is about regulating sustainable trade in flora and fauna.

And while Uthen's approach might seem outlandish, there was some sense among those attending that there may be things to learn from the private sector.

Recently, a group of scientists, writing in a leading journal, external, called for the legalisation of the trade in rhino horn.

Those researchers cited crocodiles as the model for the rhino. They said that however distasteful, allowing a legal trade in crocodile products and bringing in energetic businessmen like Uthen Youngprapakorn, had been successful in removing the need to hunt them.

Uthen Youngprapakorn explains his philosophy on conservation to delegates from the Cites meeting

As a result wild populations have recovered.

Many conservationists are horrified by these ideas - and they believe that even talking about them gives succour to those who would maim and kill creatures like rhinos, in the belief that a legal trade might happen sometime in the future.

But back on the crocodile farm, Uthen Youngprapakorn believes that profit is the key to preservation - species will not survive if they cannot pay their way.

"Some people have very conservative views - they are looking on one side, they are not seeing the whole system," he tells me.

"If you don't interest people, how do you preserve that animal? How do you develop genetics or anything? That is the wrong way, you must interest first."

And in his world, raising interest means the elephants continue to dance.