Mobile location data 'present anonymity risk'

- Published

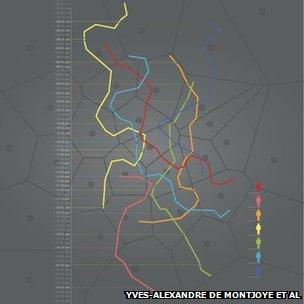

Location data may not seem personal in a crowded place - but a mobile user's path can give identity away

Scientists say it is remarkably easy to identify a mobile phone user from just a few pieces of location information.

Whenever a phone is switched on, its connection to the network means its position and movement can be plotted.

This data is given anonymously to third parties, both to drive services for the user and to target advertisements.

But a study in Scientific Reports, external warns that human mobility patterns are so predictable it is possible to identify a user from only four data points.

The growing ubiquity of mobile phones and smartphone applications has ushered in an era in which tremendous amounts of user data have become available to the companies that operate and distribute them - sometimes released publicly as "anonymised" or aggregated data sets.

These data are of extraordinary value to advertisers and service providers, but also for example to those who plan shopping centres, allocate emergency services, and a new generation of social scientists.

Yet the spread and development of "location services" has outpaced the development of a clear understanding of how location data impact users' privacy and anonymity.

For example, sat-nav manufacturers have long been using location data from both mobile phones and sat-navs themselves, external to improve traffic reporting, by calculating how fast users are moving on a given stretch of road.

The data used in such calculations are "anonymised" - no actual mobile numbers or personal details are associated with the data.

But there are some glaring examples of how nominally anonymous data can be linked back to individuals, the most striking of which occurred with a tranche of data deliberately released by AOL in 2006, outlining 20 million anonymised web searches.

The New York Times did a little sleuthing in the data and was able to determine the identity of "searcher 4417749", external.

Trace amounts

Recent work has increasingly shown that humans' patterns of movement, however random and unpredictable they seem to be, are actually very limited in scope, external and can in fact act as a kind of fingerprint, external for who is doing the moving.

The new work details just how "low-resolution" these location data can be and still act as a unique identifier of individuals.

The fairly predictable nature of human movement makes location data more unique to a given user

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Catholic University of Louvain studied 15 months' worth of anonymised mobile phone records for 1.5 million individuals.

They found from the "mobility traces" - the evident paths of each mobile phone - that only four locations and times were enough to identify a particular user.

"In the 1930s, it was shown that you need 12 points to uniquely identify and characterise a fingerprint," said the study's lead author Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye of MIT.

"What we did here is the exact same thing but with mobility traces. The way we move and the behaviour is so unique that four points are enough to identify 95% of people," he told BBC News.

"We think this data is more available than people think. When you think about, for instance wi-fi or any application you start on your phone, we call up the same kind of mobility data.

"When you share information, you look around you and feel like there are lots of people around - in the shopping centre or a tourist place - so you feel this isn't sensitive information."

Privacy formula

The team went on to quantify how "high-resolution" the data need to be - the precision to which a location is known - in order to more fully guarantee privacy.

Co-author Cesar Hidalgo said that the data follow a natural mathematical pattern that could be used as an analytical guide as more location services and high-resolution data become available.

"The idea here is that there is a natural trade-off between the resolution at which you are capturing this information and anonymity, and that this trade-off is just by virtue of resolution and the uniqueness of the pattern," he told BBC News.

Mobile phone firms are beginning to learn the value of selling aggregated, anonymised data

"This is really fundamental in the sense that now we're operating at high resolution, the trade-off is how useful the data are and if the data can be anonymised at all. A traffic forecasting service wouldn't work if you had the data within a day; you need that within an hour, within minutes."

Dr Hidalgo notes that additional information would still be needed to connect a mobility trace to an individual, but that users freely give away some of that information through geo-located tweets, location "check-ins" with applications such as Foursquare and so on.

But the authors say their purpose is to provide a mathematical link - a formula applicable to all mobility data - that quantifies the anonymity/utility trade-off, and hope that the work sparks debate about the relative merits of this "Big Data" and individual privacy.

Sam Smith of Privacy International said: "Our mobile phones report location and contextual data to multiple organisations with varying privacy policies."

"Any benefits we receive from such services are far outweighed by the threat that these trends pose to our privacy, and although we are told that we have a choice about how much information we give over, in reality individuals have no choice whatsoever," he told BBC News.

"Science and technology constantly make it harder to live in a world where privacy is protected by governments, respected by corporations and cherished by individuals - cultural norms lag behind progress."

But Mr de Montjoye stressed that there is far more to location data than just privacy concerns.

"We really don't think that we should stop collecting or using this data - there's way too much to gain for all of us - companies, scientists, and users," he said.

"We've really tried hard to not frame this as a 'Big Brother' situation, as 'we know everything about you'. But we show that even if there's no name or email address it can still be personal data, so we need it to be treated accordingly."