Charles Darwin letters reveal his emotional side

- Published

In a collection of previously unpublished letters that have been made available online today, naturalist Charles Darwin reveals a highly emotional and personal side.

In letters to his closest friend, the botanist Joseph Hooker, he pours out his grief over the death of his daughter-in-law, Amy. He also speaks of his ideas on evolution for the first time - something he writes was like "confessing to a murder".

Of the many letters that Darwin wrote and received in his life, among the most important were his correspondence with his friend of 40 years, Joseph Hooker. As well as tracking the development of Darwin's scientific ideas, the letters give an intimate insight into a Victorian friendship.

Almost the entire collection - more than 1,400 letters - has been published by Cambridge University's Darwin Correspondence Project.

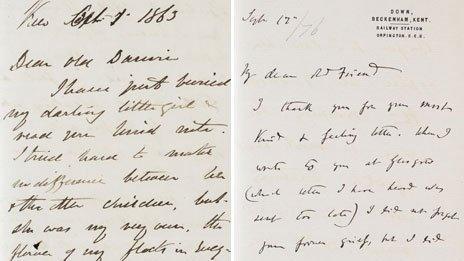

Letters between Darwin and Hooker (courtesy Darwin estate and Cambridge University Library)

It is the personal nature of the correspondence that is particularly striking. In one poignant letter, written in 1876, Darwin writes of the death in childbirth of his son Francis' wife.

"Poor Amy had severe convulsions due to wrong action of the kidneys; after the convulsions she sunk into a stupor from which she never rallied," he writes.

"It is an inexpressible comfort that she never suffered and never knew she was leaving her beloved husband for ever. It has been a most bitter blow to us all."

A few years earlier, Hooker had written to him of the death of his own daughter, addressing him as "Dear old Darwin," and going on to say: "I have just buried my darling little girl and read your kind note." Darwin is at pains to remember his friend's feelings in their shared grief.

He writes: "I thank you for your most kind and feeling letter. When I wrote to you at Glasgow (which letter I have heard was sent too late) I did not forget your former grief, but I did not allude to it, as I well knew that it was wrong in me to revive your former feelings, but I could not resist writing to you."

The letter also reveals the closeness of Darwin's family ties - in particular his concern for his son.

He writes: "I never saw anyone suffer so much as poor Frank. He has gone to north Wales to bury the body in a little church-yard amongst the mountains… I am glad to hear that he is determined to exert himself and work in every way. How far he will be able to keep to this wise resolve I know not."

Intimate window

Darwin and Hooker met as young men, after both had travelled extensively as botanists - Darwin to the Galapagos Islands aboard the Beagle, Hooker to the Antarctic. They went on to pursue very different scientific careers, with Hooker becoming director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, while Darwin developed his ground-breaking ideas on evolution by natural selection.

The two men saw each other occasionally, but their friendship was mainly conducted through letters. According to Paul White, editor and research associate at the Darwin Correspondence Project, the letters provide an intimate window onto Darwin's emotional life.

"It's a wonderful set of documents not only about Victorian science but about the social bonds that could be forged in correspondence, and the emotional bonds that could flow between two men," he says.

Darwin also used Hooker as a sounding board for his scientific ideas. Because of his position at Kew, Hooker was able to put him in touch with a wide network of scientific contacts. This was vital for Darwin, says Mr White: "It was particularly important because he had chosen to live rather a reclusive life. He didn't have an institutional position, so Darwin relied upon letters more than most people at the time for his window on the world."

It was with Hooker that Darwin first shared his radical ideas on evolution. According to Mr White, the fact he felt sufficiently confident to trust Hooker with this information that he had kept private for several years was an indication of how close they had become. Even so, his thoughts are not conveyed without trepidation.

"At last gleams of light have come, and I am almost convinced (quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable," he writes.

It is clear that Darwin was aware of the revolutionary nature of his ideas, and Hooker was to argue strongly in support of his friend in the religious debate that followed. Much of the debate was conducted through letters - with Darwin answering many of his critics personally.

Mr White suggests the letters help "to give a different picture of both Darwin and the scientific enterprise, in showing it as intensely collaborative, and that it is not divorced from private life".

In part, this was a result of the very different characters of the two men, says Mr White.

He says: "Hooker seems quite irascible, he comes across as being hot tempered and gossipy, and Darwin really loved that stuff - there was a liberating quality to their letters. He was more reserved - he had a formality and politeness. But possibly because of this he expressed things he wouldn't have otherwise."

It is this openness - as well as the light they shed on Darwin's work - that give the letters their fascination.

Paul White was interviewed on the BBC World Service programme Newshour.

- Published26 February 2013

- Published10 February 2012