Margaret Thatcher: How PM legitimised green concerns

- Published

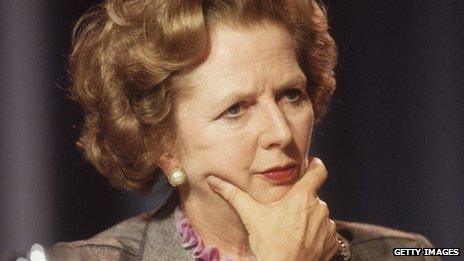

Baroness Thatcher's intervention consolidated the issue in the media and among policy makers

Mrs Thatcher arguably did more than any major UK politician at the time to legitimise the environment as a concern at the highest level.

During her brief green period in the late 1980s she shocked first the Royal Society then the UN with speeches crackling with environmental passion.

Her intervention consolidated the issue in the media and provoked many organisations into formulating policies on the environment.

She later recanted, voicing fears that climate had become a left-wing vehicle.

But her earlier remarks had already changed the institutional landscape.

The peak of her green interest was in the late 80s - a time of bubbling media coverage of acid rain, climate, waste and rainforest destruction. In 1989 she must have been alarmed when the Greens took 15% of the vote in the Euro elections.

In November 8, 1989 she told the UN, external: "While the conventional, political dangers - the threat of global annihilation, the fact of regional war - appear to be receding, we have all recently become aware of another insidious danger. It is the prospect of irretrievable damage to the atmosphere, to the oceans, to earth itself.

"What we are now doing to the world, by degrading the land surfaces, by polluting the waters and by adding greenhouse gases to the air at an unprecedented rate - all this is new in the experience of the earth. It is mankind and his activities that are changing the environment of our planet in damaging and dangerous ways."

She continued: "The result is that change in future is likely to be more fundamental and more widespread than anything we have known hitherto. It is comparable in its implications to the discovery of how to split the atom. Indeed, its results could be even more far-reaching.

"It is no good squabbling over who is responsible or who should pay. We shall only succeed in dealing with the problems through a vast international, co-operative effort.

Humdinger or humbug?

The environmentalist George Monbiot describes the speeach as well-informed humbug.

He says: "Two days before she delivered (it), the UK blocked a proposal at a conference in the Netherlands for a 20% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2005. It was Thatcher who insisted that 'nothing can stop the great car economy' and her ministers who announced 'the biggest road-building programme since the Romans'.

But the speech had an enormous impact at the time. As a former research chemist as well as a free-marketeer, her views carried even more weight than the usual Prime Ministerial utterances.

Jonathon Porritt, then head of Friends of the Earth, admitted: "It wasn't until Mrs Thatcher went into her short-lived green period that things really took off (for the green movement).

"Before Mrs Thatcher started to talk about the ozone layer and climate change, lots of people said: 'These green issues are just for weirdos treehugging. But if Mrs Thatcher's saying something like that - there must be something in it'."

Mrs Thatcher would have known better than anyone, though, that ultimately politicians would be obliged to answer the question of who is responsible and who should pay.

When I spoke to her at length about the environment two years after her UN speech, she appeared not to have spent much time grappling with the political challenges provoked by her own scientific analysis.

In 2003, her book Statecraft recanted her earlier views, casting doubt on "alarmist" science of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) - a body she helped to create - and warning that: "The new dogma about climate change has swept through the left-of-centre governing classes."

She said the international effort to tackle climate change "provides a marvellous excuse for worldwide, supra-national socialism".

The climate sceptic columnist Christopher Booker applauded her volte-face, external, arguing that previously she had been "under the spell" of her adviser the former UN ambassador Sir Crispin Tickell.

But other critics suggested that Mrs Thatcher had come to rely on dubious critiques, external of climate science from US right-wing "think tanks."

Both, of course, may be true - but her impact on the history of the environmental debate cannot be denied.

Follow Roger on Twitter, external