Blazar Markarian 421's flare-up is cosmic coincidence

- Published

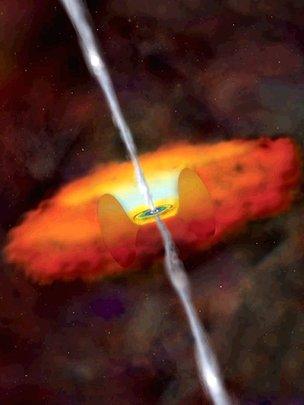

Active galaxies and the supermassive black holes they host remain mysterious to physicists

The skies are currently being flooded with the brightest display of gamma rays - the Universe's highest-energy light - ever seen by astronomers.

The culprit is a staggering flare-up of Markarian 421, a "blazar" that hosts a supermassive black hole.

By sheer coincidence, a programme to study it had just begun, so dozens of the world's telescopes - from visible to radio to gamma-ray - were watching.

And it came just in time for a meeting of many of the world's astrophysicists.

The name of Markarian 421 is cropping up in many talks at the American Physical Society meeting in Denver, external.

"It's really quite exciting because we can exchange ideas about it while we're here at the meeting in the same place," said Greg Madejski of the Kavli Institute of Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology.

Blazars are a special case of "active galaxies" - those whose supermassive black holes spray out great quantities of light across the whole electromagnetic spectrum as they feed on surrounding matter.

Active galaxies emit jets of light - up to trillions of times more energetic than the light we see - and a blazar is one with a jet pointing toward the Earth.

What remains a mystery is how gamma rays are created at such extraordinary energies.

'Miraculous'

Markarian 421 was already in the known catalogue of blazars, being somewhat variable and having had something of a brightening, or flare, in 1996.

But the one that began late last week was unprecedented in the history of observations.

"I'm in shock and awe at how bright it is," said Julie McEnery, project scientist for the Fermi gamma-ray telescope.

"This thing is blowing us away," she told BBC News.

Fermi and a laundry list of the world's great observatories on the ground and in space were all watching because of a coordinated plan to study Markarian 421 across a number of "colours" of light from radio to gamma-ray.

"It's correlating the increasing intensity in different bands that provides really important clues about the structure of the source," Prof Madejski - a co-investigator on the NuStar X-ray telescope, told BBC News.

"In this case, we actually had designed a campaign to study this source, and it cooperated in a miraculous way. We never know when exactly it's going to get very bright and this time it was kind enough to do just that when we had a very large number of telescopes trained on it."

The hard work now begins, as the observatories share their recordings from recent days. Astrophysicists can determine how the blazar grew brighter in different parts of the spectrum at different times and refine their models of how fast-moving particles within the jets give rise to the high-energy light.

"It's going to give us a lot more info about how those particles get energised to provide this spectacular event," Prof Madejski said. "Now we're drinking from a waterfall."

- Published15 April 2013

- Published30 August 2012

- Published12 July 2011