Toba super-volcano catastrophe idea 'dismissed'

- Published

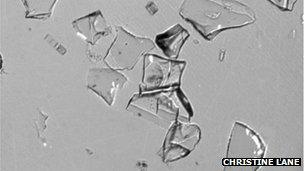

Toba traces: The volcanic glass fragments are thinner than human hair

The idea that humans nearly became extinct 75,000 ago because of a super-volcano eruption is not supported by new data from Africa, scientists say.

In the past, it has been proposed that the so-called Toba event plunged the world into a volcanic winter, killing animal and plant life and squeezing our species to a few thousand individuals.

An Oxford University-led team examined ancient sediments in Lake Malawi for traces of this climate catastrophe.

It could find none.

"The eruption would certainly have triggered some short-term effects over perhaps a few seasons but it does not appear to have switched the climate into a new mode," said Dr Christine Lane, external from Oxford's School of Archaeology.

"This puts a nail in the coffin of the disaster-catastrophe theory in my view; it's just too simplistic," she told BBC News.

The results of her team's investigation are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), external.

Glass signature

The Toba super-eruption was the biggest volcanic blast on Earth in the past 2.5 million years, and probably further back than that as well.

Researchers estimate some 2,000-3,000 cubic kilometres of rock and ash were thrown from the volcano when it blew its top on what is now the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

Much of that debris landed close by, piling hundreds of metres deep in places. But a lot of it would also have gone into the high atmosphere, blocking out sunlight and cooling the planet. Sulphurous gases emitted in the eruption would have compounded this effect.

The cores record climate changes in East Africa stretching back half a million years

Some scientists have argued that the winter conditions this would have induced could have posed an immense challenge to early humans and have pointed to some genetic studies that indicated our ancestors likely experienced a dramatic drop in numbers - a population "bottleneck" - around the time of the eruption.

The Oxford team reasoned that if this perturbation was so great, it ought to be evident in the sediments of Lake Malawi.

This body of water is some 7,000km west of Toba in the East African Rift Valley, from where our Homo sapiens species emerged in the past 100,000 years or so.

The lake is said to retain an excellent record of past climate change which can be inferred from the types and abundance of algae and other organic matter found in its bed muds.

Tens of metres of sediments have been drilled to retrieve cores, and it these recordings of past times that Dr Lane and colleagues examined.

They identified tiny glass shards mixed in with the muds almost 30m below the lake bed. The shards represent small fragments of magma ejected from a volcano that have "frozen" in flight.

"They're smaller than the diameter of a human hair, less than 100 microns in size," explains Dr Lane. "We find them by sieving the sediments in a very long process that goes through every centimetre of core." Chemical analysis ties the fragments to the Toba eruption.

Re-timed droughts

The shards are present only in traces, but indicate the eruption spewed ash much further than previously thought - about twice the distance recorded in other studies.

But the investigation finds no changes in the composition of the sediments that would indicate a significant dip in temperatures in East Africa concurrent with the Toba eruption.

The crater at Mount Toba in Indonesia is itself now the site of a large lake

What is more, the presence of the shards has allowed researchers to more accurately time other climate events that are seen in the cores. This includes a group of huge droughts previously dated to occur some 75,000 years ago. These have now been pushed back at least 10,000 before the eruption.

"All long records like the Malawi cores are very difficult to date, particularly when you get beyond the limits of radiocarbon dating which is 50,000 years. So having a time marker like Toba in the cores is really exciting."

Major reductions in population size leave their mark on genetic diversity of modern individuals. For Homo sapiens, such bottlenecks are evident some 100,000 years ago and 50,000-60,000 years ago - both probably related to migrations out of Africa.

Dr Chris Tyler Smith studies genetics and human evolution at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK. He said the Toba theory was a popular one a few years ago, but more recent study had led most researchers to move on from the subject.

"It was an exciting idea when it was first suggested but it just hasn't really been borne out by subsequent advances," he told BBC News.

Dr Lane's team included Ben Chorn and Thomas Johnson from the University of Minnesota, Duluth, US.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published30 May 2012

- Published23 June 2011

- Published27 January 2011

- Published20 September 2010