Saluting 'local heroes of conservation'

- Published

- comments

Under pressure: Preuss's Red Colobus monkey

"It smells like a dead body," the customs officer told me, as we opened a crate of smuggled ivory in the cargo terminal at Bangkok airport earlier this year.

The pieces of tusk were so numerous that a total of 79 elephants had been slaughtered to yield this haul destined for the remorseless markets of China.

The smell was indeed funereal: musty, pungent, depressing.

So much about the endless plunder of wildlife around the world - and the apparent failure of international agreements to stem the losses - is a cause for despondency.

Cross-border policing efforts are being stepped up but all too often the police themselves are involved in the trade. The money is easy and the pickings rich.

It's far easier to kill elephants, tigers and gorillas than to save them.

So it's always uplifting to hear stories about the handful of people brave enough to stand up and intervene. They have a lot stacked against them: indifferent or corrupt authorities, powerful criminal gangs, long-held traditions about how to make a living.

One of the plucky few is from Cameroon. Ekwoge Enang Abwe runs a project to try to safeguard the creatures of the Ebo Forest: the gorillas, chimpanzees and monkeys that are pillaged for bushmeat. Unchecked, the trade would wipe them out.

I met Ekwoge through a small conservation charity, the Whitley Fund for Nature. He is one of eight winners of this year's Whitley Awards, external (Read more about the winners here).

His challenge was to confront an entire economic system based on exploiting the forest for its animals. As many as 2,000 were being killed every week as traders from the cities brought traps and ammunition to equip the hunters for their grim ventures into the jungle.

How could he possibly hope to turn this around?

Ekwoge Enang Abwe: "Pride" is a powerful force

"Pride," he told me. "We've been appealing to the sense of pride of the communities. We used pride as a tool.

"We explained to them how the animals are special, how they're often unique, and that they could have a role in saving them."

Only 25 gorillas, from a sub-species, are left in the forest. The chimps are the only ones known both to fish for termites and use rocks to crack nuts. The Preuss's Red Colobus monkeys only live in one other habitat.

"So we educate the people and the chiefs about how special these animals are and how alternative livelihoods are possible."

The hunters have been encouraged to turn to cocoa farming. The chiefs have come together from previously divided clans to discuss setting up systems for keeping watch on poachers. A census of gun holders will take place.

Ekwoge's hope is that the forest will be granted the status of a National Park, a move which would give it more protection. National government does have a role but the impetus is local. And without a change in local attitudes - a revolution in thinking about the natural world's value - none of this would have been possible.

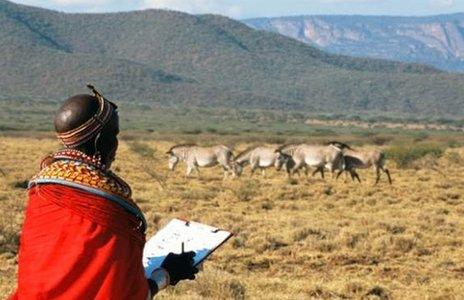

Another winner, Daniel Letoiye, a Samburu from Kenya, also says that the decisive factor is the support of his local community. His project is to restore the grasslands left barren by years of drought and overgrazing.

The logic of rotation: The grasslands have been recovering

Initially his plan to reseed particular areas - and to keep the cattle away for up to three months - was met with hostility.

"There was a lot of opposition. People were saying, 'Why are you taking our land?' They didn't like the idea at all," Daniel recalls.

But after the first year when the grasses started to return, people saw the logic of agreeing to rotate the animals. The plans made sense.

And having healthier pastures allows native animals to recover too. Grevy's Zebras - notable for their relatively large size, narrow stripes and large ears - are down to just 2,400.

Continued degradation of the land and poaching would have finished them off. A traditional belief was that the zebras' fat was effective medicinally.

"A big theme is co-existence," says Daniel. "We have shown that the zebras can co-exist with the cattle and the tourism brings in an income of $80,000 a year."

Grevy's Zebras display narrow stripes and large ears

Projects like these are chinks of light in an otherwise pretty gloomy international picture. Other winners include the people behind Turkey's first wildlife corridor and marine reserve, and schemes to save hornbills in India, turtles in Bangladesh, gorillas in Congo and wildlife in the headwaters of the Amur River.

Daniel Letoiye: "A big theme is co-existence"

They win £25,000 each - not a huge amount, but enough to help raise their profiles enough to start attracting political support.

For the Trust's founder, Edward Whitley, an important feature is that the initiatives are not imposed by "experts" flying in from outside.

He describes being dismayed by the sight in Madagascar of "the gleaming white Landcruisers of the international community" and wants to give local "heroes of conservation a leg-up".

It'll take more than this to halt the wildlife horror stories in so many countries. But after inhaling the stench from one of those crates full of smuggled ivory, it's a very welcome start.