Ant studies to aid design of search and rescue robots

- Published

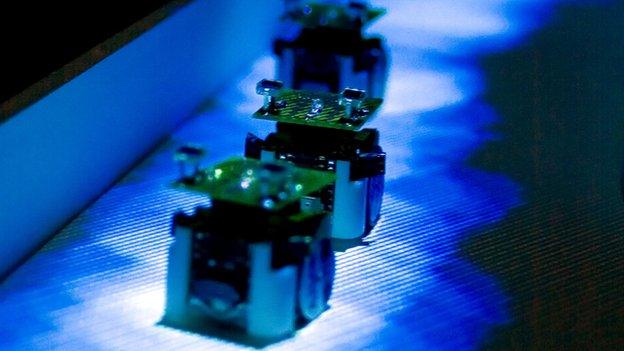

In a 2013 study, Prof Dan Goldman and his team discovered how fire ants managed to tunnel so swiftly through fine, unstable sand

A study showing how ants tunnel their way through confined spaces could aid the design of search-and-rescue robots, according to US scientists.

A team from the Georgia Institute of Technology found fire ants can use their antennae as "extra limbs" to catch themselves when they fall, and can build stable tunnels in loose sand.

Researchers used high speed cameras to record in detail this behaviour.

The findings are published in the journal PNAS, external.

Dr Nick Gravish, who led the research, designed "scientific grade ant farms" - allowing the ants to dig through sand trapped between two plates of glass, so every tunnel and every movement could be viewed and filmed.

"These ants would move at very high speeds," he explained, "and if you slowed down the motion, (you could see) it wasn't graceful movement - they have many slips and falls."

Crucially, the insects were able to gather themselves almost imperceptibly quickly after each fall.

To see how they managed this, the team set up a second experiment where, to move from their nest to their food source, the ants had to pass through a labyrinth of smooth glass tunnels.

"We could watch these glass tunnels and really see what all the body parts were doing when the ants were climbing and slipping and falling," said Dr Gravish.

Fire ants are able to tunnel through almost any type of soil, a key reason why they are such a successful invasive species

The researchers were surprised to see that the ants would not just use their legs to catch themselves, but also engaged their antennae, essentially using these sensory "sniffing" appendages as extra limbs to support their weight.

Tune the environment

Finally, the researchers wanted to look inside the hidden labyrinths that the ants constructed underground, so they put ants into containers full of sand or soil and allowed them to dig.

They then built a "homemade X-Ray CT scanner", just like a medical scanner, to take 3D snapshots of the tunnels that the ants dug in different types of soil.

"We found that ant groups all dug tunnels of the same diameter, [no matter what the] soil conditions were," said Dr Gravish.

"This suggested to us that fire ants are actively controlling their excavation to create tunnels of a fixed size."

Keeping their tunnels at approximately one body length in diameter seemed to ensure that the ants could catch themselves when they slipped and allowed the creatures to continue to dig.

Prof Dan Goldman, who was also involved in the study, explained that these remarkably successful insects were able to manipulate their environment - using it to control their movement.

His overall aim, he explained, was to distil "the principles by which ants and other animals manipulate complex environments" and bring them to bear in the design of search-and-rescue robotics.

"The state of the art search-and-rescue robotics is actually quite limited," he told the BBC.

"Lots of the materials in disaster sites - landslides, rubble piles - are loose materials, which you're going to potentially have to create structures out of.

"You might want, for example, to create a temporary structure for people buried down beneath."

Fire ants, he explained, could build stable tunnels in sand or soil with almost no moisture to bind it together, so learning from them might enable designers to build and programme robots that solve these same engineering problems.

- Published29 March 2013