A350 marks new phase in aero-engines

- Published

- comments

Blades are made of a nickel-based alloy and are grown in a single crystal

A UK aircraft engine claimed to be the most efficient in the world faced its toughest test on Friday.

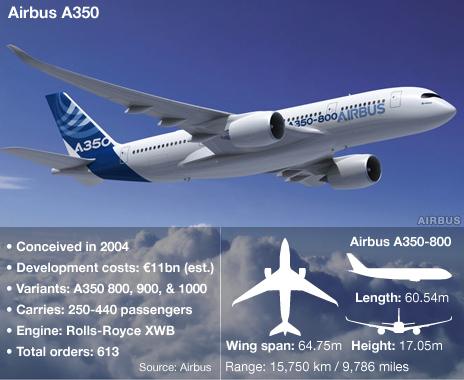

A Trent XWB, produced by Rolls Royce, was fitted to the new Airbus A350, which made its debut flight from Toulouse, France.

The new engine includes novel technologies designed to shave off weight and minimise fuel consumption.

It is the latest twist in the fierce contest between Airbus and Boeing, which recently launched its Dreamliner.

And to that battlefield, you can also add Rolls-Royce and its US rival General Electric.

Orders for aero engines are worth billions so the competition to win customers is intense.

The Trent XWB was custom-designed for the A350, and more than 1,200 of the engines have so far been requested.

BBC News was given rare access to the Rolls-Royce factory in Derby to watch the production process.

The first striking feature is the sheer scale of the machine - the diameter of the set of fan blades at the front of the engine is 118 inches (299cm), the largest ever made by the British company and roomy enough to accommodate the fuselage of a Concorde.

The blades themselves, made of titanium, are hollow and strengthened inside by a microscopically small grid construction. GE has opted for fan blades made of composite materials.

The size of the fan enables the engine to suck in enough air to fill a squash court every second, and then squeeze it to the size of a fridge-freezer - what's known as a "compression ratio" of 50 to 1, the highest pressure Rolls-Royce has yet attained.

The larger the flow of air into the engine, and the greater the potential compression, the better the efficiency of the whole process.

Chris Young, Rolls-Royce: "You could fit the Concorde fuselage through the engine casing"

When the mix of fuel and air is ignited, the resulting gas reaches an extraordinary temperature of 2,200C - a higher level than has been achieved before - which is meant to maximise the output of each drop of fuel.

The searing heat of 2,200C is in fact 700C hotter than the melting point of the components in the combustion chamber - including the turbine blades that are driven by this fast-expanding gas.

So each blade is drilled with a network of 300 tiny holes about the size of a human hair. This allows cooling air to flow in a thin film over the turbines' surface and act as a form of insulation.

To withstand this exceptional heat - and the massive pressures involved - the 68 turbine blades are made of a nickel-based alloy and are grown in a single crystal to avoid the risk of any internal fissures becoming sources of weakness.

The result is that each blade, driven by the expanding gases, generates as much power as a Formula One car, spinning an internal shaft that drives the massive fan blades at the engine's front.

Testing has involved running the power unit in freezing temperatures...

According to Chris Young, director of the XWB project, the engine is the result of several years of work by scientists and engineers seeking a series of incremental improvements.

"There are a large number of individual technologies in there, individual system designs which contribute a per cent here, half-a-percent there, a few tenths there.

"We've managed to deploy all the latest technologies on the engine - it's the most recently developed, and by putting all that together it's the world's most efficient."

On average, aircraft engines have become about 1% more fuel-efficient every year for the past two decades.

The claims by Rolls Royce will inevitably be followed by similar assertions by GE when its next engines are unveiled.

Airlines facing rising fuel prices are desperate to reduce costs, and the aviation industry as a whole is also under pressure to minimize its carbon emissions.

But as the latest generations of engines become more efficient, any reductions in greenhouse gases are outweighed by the global growth in air traffic, especially in Asia.

...and flying a power unit (blue engine) on the huge A380 superjumbo

Dr Peter Hollingsworth, lecturer in aerospace engineering at Manchester University, said that basic physics meant that there were likely to be limits to how much more efficiency could be extracted from existing designs.

"It's a real challenge. With aviation growing at the rate it's growing, there's not a whole lot you can do. You can do the 1-2% average so over a number of years you get 20% but even that's a real challenge.

"Now that engines are a lot more efficient, a 20% improvement isn't worth as much as it was, so you're always working with diminishing returns and, at the same time, aviation is growing."

The aviation industry has set itself a target of a 50% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 compared with 2005 levels - and there's a recognition that that will only be achievable with a revolutionary shift in designs.

Among the ideas being considered are engines that are embedded within the wings and contra-rotating propellers.

Alan Newby, chief engineer for advanced projects at Rolls-Royce, said: "Ultimately, if we're going to make these radical changes then the aircraft will have to starting looking different.

"It's probably not in the 2020s but beyond 2030 if we're going to achieve the targets we need to get for our customers and the environment."