Sabretooth killing power depended on thick neck

- Published

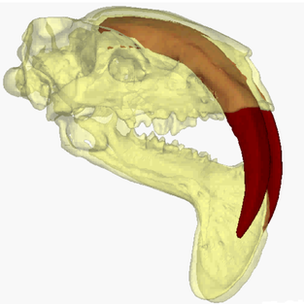

This marsupial pouched killer (pictured in an artist's interpretation) had bigger canines than those of other similar-sized sabretooth beasts

Scientists have analysed how an extinct sabretooth animal with huge canines dispatched its prey, finding that strong neck muscles were vital for securing a kill.

The marsupial, which terrorised South America 3.5 million years ago, had the biggest canine teeth for its size.

Experts say the big beast possessed extreme adaptations to the "sabretooth lifestyle".

The killing behaviour of Thylacosmilus atrox is described in Plos One, external.

Until now, the extinct sabretooth "tiger" Smilodon fatalis has received most attention as a ferocious sabretooth predator.

Thylacosmilus's canine teeth were extremely close to its brain

But millions of years earlier, a pouched marsupial was one of dozens of sabretooths that had roamed the Earth before the better known Smilodon, which went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age.

Like Smilodon, Thylacosmilus had highly specialised canines adapted to kill large beasts but until now little was known about the exact way it killed its prey.

Scientists took CT scans of fossil remains to construct high-resolution digital 3D models of both sabretooth beasts, and compared them with the modern leopard.

The simulations were digitally loaded with forces to see how the animals would have behaved when biting and killing prey.

Weak bite

The work was led by Stephen Wroe from the University of New South Wales, Australia, who explained that Thylacosmilus's closest living relatives are Australian and American marsupials.

"We found that both sabretooth species were similar in possessing weak jaw-muscle-driven bites compared with the leopard, but the mechanical performance of the sabretooths' skulls showed that they were both well-adapted to resist forces generated from very powerful neck muscles," he told BBC News.

For its size - Thylacosmilus's huge canine teeth were larger than those of any other known sabretooth. The roots of these canines went back to within millimetres of its very small brain case.

"Thylacosmilus was even more extreme. Its skull easily outperformed that of the placental Smilodon and was much better adapted to resist forces incurred by a neck-driven bite."

This adaptation was vital as its long thin canines were vulnerable to snapping. To hunt, the animal had to secure and immobilise large prey using its powerful forearms before inserting its long canines into the windpipe or major arteries of the neck - "a mix of brute force and delicate precision".

Thylacosmilus secured a kill with its very powerful neck muscles

These adaptations allowed for a relatively rapid kill of dangerous big prey.

"The bottom line is that the huge sabres of Thylacosmilus were driven home by the neck muscles alone - and - because the teeth were actually quite fragile - this must have been achieved with surprising precision," said Dr Wroe.

"It may not have been the smartest of mammalian super-predators, but in terms of specialisation Thylacosmilus took the already extreme sabretooth lifestyle to a whole new level, which clearly exceeded that of the much better known sabretooth tiger."

- Published17 May 2013