Can Germany afford its 'energy bender' shift to green power?

- Published

Germany's rapid transition to renewable energy is said to be the country's biggest and most expensive project since the fall of the Berlin wall - but with rising costs for consumers and industry, will this great energy experiment succeed?

The powerful whiff of farmyard manure cannot dim the smiles on people's faces in the German village of Juehnde.

Located in the heart of the country, this rural community is home to Germany's first energy co-operative, external that started in 2005.

The co-op generates electricity from solar panels and from a biogas plant that mixes locally grown grain and locally sourced farm waste.

The residents are happy because they get cheap power and heat and thanks to the feed-in tariff laws, external that allow them to sell the surplus energy to the national grid, they bank a healthy annual return on their investment to boot.

"It makes money," says Eckhard Fangmeier with a quiet grin. He has been with the co-op since the start.

"We are a very small, rural place, with normal people.

The success has been based on the feed-in tariff, without it we couldn't live here in an economic way. It's a basic."

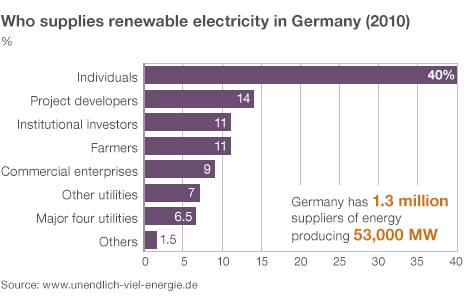

Across Germany, co-operatives, farmers and homeowners are part of the 1.3 million renewable energy producers who have taken advantage of this generous tariff scheme. It pays a fixed price for 20 years. More importantly, it guarantees priority access to the grid, ahead of the big utility companies.

As a result, houses now sport shiny solar cells on their roofs and wind turbines are spreading through the country like a giant metallic army.

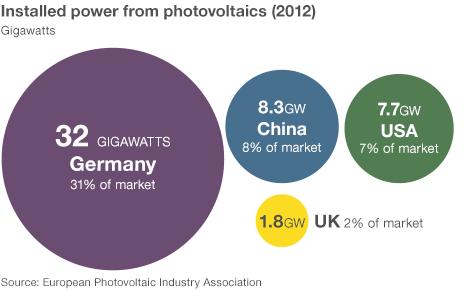

Across Bavaria, it is said there are more photovoltaic panels installed than in the entire United States.

Battle for Berlin

This being Germany, this remarkable transformation has a name. It is called the Energiewende, or energy transformation. The rapid take up of renewables means that in 2012, these green entrepreneurs provided 22% of Germany's electricity, external.

And it doesn't stop at electricity generation. The Energiewende is encouraging change throughout the system.

On the busy streets of Berlin, 26 year-old Arwen Colell wheels her bike to choir practice. A political scientist, she leads a community co-operative, external that wants to take control of the capital's electricity grid with its 35,000km of underground cables.

She is battling established energy companies and the Chinese state grid. But so far 1,300 Berliners have invested cash in the venture. Arwen wants to build a grid that can better handle the rise of green power.

"The most important thing with distribution is that you have renewables flooding the grid directly," she says.

Arwen Colell leads a community group bid to take control of the Berlin electricity grid taking on a number of challengers including the Chinese state

"You have to balance incoming and outgoing energy.

"That's something the structure has to accommodate, and these structures are old, and they have to be rebuilt from the bottom up to cope with this bi-directional energy flow."

Across the city, at a newly built apartment block overlooking the headquarters of Germany's secret service, Annette Jensen has just moved in to her new home.

It is one of the first passive houses in Berlin where curbing the use of energy is literally built into the fabric of the building.

Insulation is critical and air intake is carefully controlled. Warm air from the kitchens and showers passes through a heat exchanger and up to 90% of it is recovered.

Annette says the system works well, and is extremely economical.

"We will have to pay around 300 euros a year for our energy bills; normally people pay 100 euros a month," she explained.

"I don't sacrifice my comfort, that's not the way to the future - you don't have to miss anything."

But all these astonishing strides are coming at a high cost. Consumers pay directly for green energy through their bills. This year around 50% of an average bill, external will be made up of taxes and levies for renewables.

Green hangover

Critics of the Energiewende have dubbed it the "energy bender", a play on the German pronunciation. They say the plan is economic madness, with bill payers spending 18bn euros (£15bn; $23bn) every year on electricity with a market value of 3bn euros (£2.8bn; $3.8bn).

"I think the hangover from the energy bender for us is that we have to pay for our extremely ambitious extension of renewables for years and years," says Florian Rentsch, minister for economics in the region of Hesse.

Solar power has expanded rapidly in Germany even though the country has the same level of sunlight as Alaska

"The law on renewable energy will not only lead to increased electricity prices, but it is also a non-market, planned system that endangers the industrial base of our economy."

This view is supported by Prof Colin Vance from the German economic research institute RWI, external.

"I definitely think there will be a cost hangover with it," he said.

"The least competitive renewable energy is getting the most support. There is a certain insanity to it, yes.

"By our calculations, we estimate that for solar power alone, it is more than 100 billion euros over 20 years."

As well as growing concerns about the cost, there are worries that the financial incentives have brought too many renewable sources to the market at the same time.

Germany is not a country known for its exposure to the Sun. However, the scale of installed solar capacity means that on a bright day, the country is overwhelmed with sunny electricity.

On 16 June this year, solar and wind energy combined, external to produce 60% of Germany's power needs. So much solar was coming into the grid that wholesale prices on that afternoon were, for a time, in the negative.

For the big utility companies, this is a nightmare scenario. Their business model means they recoup their investments in large gas- and coal-fired power stations by a steady demand for their electricity over a long period of time.

But because the feed-in tariff gives small renewable producers priority access to the grid, the big boys can only make money when the Sun doesn't show and the wind doesn't blow.

On days like 16 June, expensive gas-fired power plants stood idly by while the solar cells sizzled.

Back to coal

To curb their costs, these corporations have turned to the cheapest possible electricity sources - including brown coal or lignite, which is one of the most carbon-intensive fuels.

Because of this, Germany's CO2 emissions went up in 2012, external, despite renewables never having a larger share of the market. The fossil-fuel energy producers are demanding change.

"At the moment, the energy transition is at a crossroads," says Peter Englehard from RWE, one of Germany's big four utility companies.

"It is driven by subsidies and administrative intervention, where it should be more market-based. We have to bring more market into this, otherwise it will drown in too much subsidised power."

There is general political support for the Energiewende amongst the major political parties.

The German government has ambitious targets for cutting overall energy consumption by around 40% by 2050. In the plan, renewables will make up half the electricity supply, and a third of total energy, including transport, by 2030.

But there is also an emerging consensus that there should be changes to cut the costs of the programme.

Minister Rentsch, whose party is in the governing Federal coalition, says that changes are necessary and likely to take place after the general election in September.

"If the energy prices for the transition will increase in the next years, I think the Energiewende will lose acceptance in our society," he argues.

Wind farms have benefited from high subsidies paid directly by the consumer

But with strong financial support in place until the middle of the 2020s, politicians, consumers and even utility companies say there is no going back.

And according to Dr Ralf Fuecks, the head of the Heinrich Boell foundation in Berlin, the transition has not just changed the energy supply, it has changed attitudes to consumption as well.

"It is not about going backwards - green is not about departing from the modern lifestyle," he says.

"We are progressing into a moral economy. Morality is not a contradiction to economic success. It is the other way around."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external.

- Published27 February 2013

- Published30 May 2011

- Published9 August 2012