South Georgia rat removal hits milestone

- Published

The brown rat was introduced to South Georgia on sealing and whaling ships over 200 years ago. It's a ferocious predator and feasts on the chicks and eggs of ground-nesting seabirds

The world's largest rat eradication campaign has laid toxic bait on a further 580 sq km of South Georgia, reaching its target.

These poisonous pellets have now been spread on 70% of the rat-infested island.

First introduced on sealing and whaling ships in the late 18th Century, millions of invasive rats have long been a threat to local wildlife.

The team is confident they will eradicate the rodents within two years.

South Georgia is famous for its rich wildlife but as sailors plundered the ocean for seals and whales, they unknowingly brought with them the common brown rat.

The unwelcome visitors multiplied quickly as they bred and for over 200 years have feasted on the chicks and eggs of ground-nesting seabirds, which include ducks, diving petrels and prions.

Extinction fear

Species like the South Georgia Pipit and the South Georgia Pintail are unique to the island and there is now a growing concern that many local birds are at danger of extinction.

The island is separated by several glaciers, so once rats have been eradicated from a region, they cannot repopulate it.

But as the climate warms the island's natural glaciers are slowly melting. As this continues, there will no longer be a natural barrier preventing the rats from spreading.

.jpg)

South Georgia is home to the South Georgia Pintail which are unique to the island but wildlife groups are worried it's at danger of extinction

The South Georgia Pipit is also indigenous to the island but rats have vastly reduced its numbers

The latest mission saw 183 tonnes of toxic pellets distributed thinly across the island to reach every rodent territory from sea level to mountain top

As the island is separated by glaciers, once rats have been eradicated from a region they cannot repopulate it, but these glaciers are receding due to climate change

The team had to be ready to move at first light as the wind was calmest immediately after dawn

Areas which could not be reached by helicopter were hand baited, such as old whaling stations - areas where elephant seals now rest

Tony Martin, the project's director from the University of Dundee, described the mission as "a race against time", as the melting glaciers could make the task of removing them nearly impossible.

"What's there today is but a shadow of what was there when Captain Cook discovered [the island] in 1775.

He explained that species like the fabulous Wilson Storm Petrel, which were once present in the millions have all left the main island.

"There are still a few rodent-free islands around the coast from which the main island can be re-colonised. We are trying to allow the sea birds to reclaim their ancestral home.

"The ecosystem of South Georgia evolved in the absence of any terrestrial mammals, so when man came along... and introduced these furry rodents, they were completely naive. This is a man induced problem and it's about time that man put right earlier errors," Prof Martin said.

"Team rat", as they call themselves, embarked on the first phase of the eradication project in 2011, and successfully removed rats from a tenth of the island.

Total eradication

The team purposely left time between missions to observe if any survivors had managed to reproduce but, two years on, the area remains rat free.

For the latest mission the team spread nearly 200 tonnes of pellets using helicopters which enabled them to cover large areas very quickly.

They dropped pellets in every area mice or rats occupied and areas which cannot be reached by helicopter were baited by hand - this included former whaling stations which are now industrial heritage sites.

Prof Martin explained that to be successful meant total eradication.. Killing 99.9% would be a failure.

The team encountered days of terrible weather, including blizzards and gale force winds

"If you leave one pregnant female - we all know how quickly rats breed - we would be back to where we were."

For this latest phase, for which the team had spent 21 months in preparation, they faced the harshest weather conditions experienced in a decade and were often unable to fly.

The bait was attached underneath the helicopters which meant strong wind could easily strain the aircraft. They encountered turbulence "virtually every single day", helicopter pilot George Phillips told BBC News.

"It was very difficult to tell when the turbulence was coming, that's why it took such a long time. On one particular period we had eight wind-free days where the helicopters were able to fly continuously.

"In those days, the pilots did as much flying as you would do in the UK in two months."

Mr Phillips recalled how after four days at sea, he was stunned by the beautiful terrain of the island.

"It's a completely natural uninhabited environment that is so extreme with high mountains, glaciers and seals that are so wild they come up to you like little Alsatian puppies."

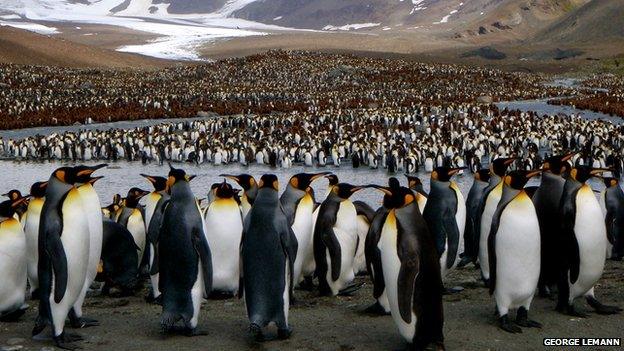

South Georgia's abundant wildlife includes four species of penguin who nest on the island

The project will need to raise a further £2m in order to bait the remaining area at the southern end of the island, which they aim to complete in 2015.

Even when rat free, the wildlife is not expected to return immediately as to re-colonise the island could take decades if not centuries, said Prof Martin.

"Man managed to mess up South Georgia in the space of very few years but it's going to take centuries before it gets back to where it was."

Though challenges remain - not least to find the additional funding needed, Prof Martin said his team is confident they can win this race against time.

- Published1 March 2013

- Published29 November 2012

- Published5 May 2011