Next Nasa Mars rover to hunt ancient life

- Published

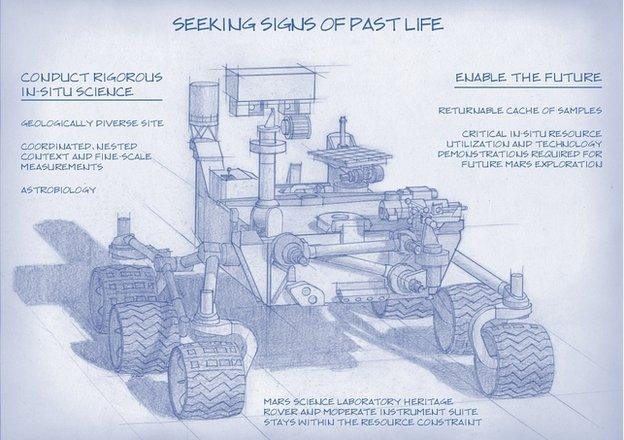

The rover the US space agency (Nasa) sends to Mars in 2020 will look for signs of past life.

It will carry a suite of instruments that will attempt to detect the traces left in rocks by ancient biology.

The mission is a subtle step on from the current Curiosity rover, designed to establish if the planet has ever had habitable environments in its history.

But the 2020 mission, external will still not be an explicit hunt for present-day life on Mars.

The Science Definition Team commissioned by Nasa, external to scope the new rover says such a search would be extremely difficult given what we know about the harsh surface conditions on the planet, and the state of current technologies.

An extant life detection mission looking for microbes would have very low probability of success, the group concluded.

"That's a darn hard measurement to make and a darn hard measurement to convince the sceptical science community, because scientists are naturally sceptical," explained Jack Mustard, team chair and professor of geological sciences at Brown University.

"The science definition team wrestled with this question, but the feeling was, on the basis of the evidence we have today, the most logical steps forward were to look for the ancient forms of life that would be preserved within the rock record."

Curiosity copy

That means sending the vehicle to a location that was likely to have been habitable billions of years in the past when the planet was warmer and wetter than it is now.

The next rover will borrow heavily from designs and lessons learned for the current Curiosity mission

This will include locations that just lost out in the site selection process for Curiosity, but will no doubt also add a few not previously considered.

To keep costs for the mission within its $1.5bn envelope, the new rover will be a near-copy of Curiosity.

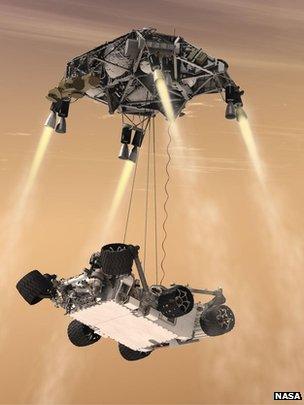

Nasa intends to incorporate many of the same design features, most notably the novel entry, descent and landing (EDL) system.

This used a hovering "skycrane" that was able to put Curiosity down with pin-point accuracy in Gale Crater.

The big difference will be the instrument suite, ideas for which Nasa expects to solicit later this year.

The science definition team says the robot should be capable of visual, chemical and mineralogical analysis down to microscopic scale.

One key ability the group wants the next rover to have is sample collection and caching.

The idea is that small cores of the most interesting rocks or soils will be packaged for later return to Earth.

Human goal

Precisely when, or how, this material would be retrieved has not been worked out, but Nasa's science director John Grunsfeld said he hoped it could be achieved sometime in the 2020s or 2030s.

"I wouldn't rule out that human explorers will go and retrieve the cache," he told reporters.

"That's the eventual goal - to put astrobiologists and planetary scientists on the surface of Mars.

"Of course, they would bring back many more samples as well. But that's all forward work."

Some of the winning instrument ideas will certainly be relevant to future human exploration.

President Obama challenged Nasa to try to send people to the Red Planet in the 2030s, and a portion of the money going into the new mission will come out of the human space exploration budget.

This raises the possibility of the rover being used to test some technologies that astronauts might need on the surface to exploit local resources such as water, or to understand better the hazards human explorers might face.

Already, Curiosity is measuring the radiation risks on the planet.

Before the new rover gets to Mars, Nasa will send two other missions. One of them is a satellite called Maven which will study the atmosphere. This will launch later this year.

The other venture is a static lander called InSight, which will listen for "Marsquakes" to improve our knowledge of the planet's interior. Insight is scheduled to launch in 2016.

Nasa first announced its intention to send a follow-up rover to Mars in 2020 at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco last December.

- Published21 June 2013

- Published18 June 2013

- Published20 August 2012

- Published30 May 2013

- Published4 December 2012