The receding threat from 'peak oil'

- Published

- comments

David Shukman takes a helicopter flight over California's vast oilfields

Concerns about oil supplies running dry are receding, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Massive new discoveries in the US have led to a "dramatic" change in global prospects.

The IEA's head of oil markets, Antoine Halff, says forecasts have had to be repeatedly revised upwards in the past two years.

Declining US production has been reversed as oil extracted from shale and other new sources comes on stream.

Mr Halff told BBC News that concerns about an approaching "peak" in oil production have been "moved to the back burner".

"Just a few years ago, everybody thought US production was in permanent decline, that the nation had to face the prospect of continuously rising imports - and now the country is moving towards self-sufficiency," he explained.

"In the last few years, many forecasters have had to revise their forecasts upwards continuously - sometimes the ink was not dry on the previous forecasts before they had to raise their outlooks again."

Developments in major new fields in Texas and North Dakota are behind the change in US oil fortunes, with the so-called Monterey shale beneath California also in prospect.

According to one IEA estimate, the US may be on course to produce as much oil as Saudi Arabia by 2020, and possibly as soon as 2017.

Technological revolution

New technologies have made it possible to exploit oil trapped in types of rock, particularly shale, that were previously thought too difficult to access.

The same techniques that have enabled the extraordinary rise in shale gas production can be used to reach oil as well.

Visualisations of seismic data in 3D are one new tool being used to help understand patterns in the geology, and in particular to identify formations of shale that might contain oil or gas.

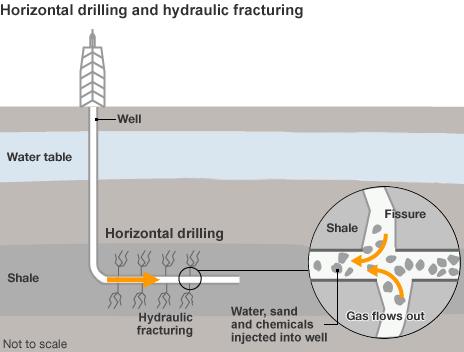

The technique of horizontal drilling - the ability to steer drills laterally through rock - has opened up the possibility of extracting oil from entire layers of shale.

And the controversial practice of "fracking" - fracturing rock under high fluid pressure - allows oil and gas to be freed from rocks previously considered too tightly-packed to exploit.

This follows a pattern of technical innovations to find new ways of extracting oil from existing fields that might otherwise be depleted.

In central California, where the first oil wells began to flow as far back as the 1890s, the oil originally emerged from the ground under its own pressure.

In the 1940s, operators had to introduce the technique of injecting steam into the wells to free up the oil and flush it to the surface, a method still in use today.

More recently, horizontal drilling - in which drills reach more than a mile down and then along - has reached reserves otherwise considered closed.

According to one independent oil producer, Fred Holmes of Holmes Western, the key factor is a high price for oil, making it worthwhile to continue exploiting existing fields and explore new ones.

"There's still plenty of oil - we just haven't got all of it out of the ground yet. There's not a real danger of there being no fossil fuel… the oil is still valuable and it's not easy to get," he told BBC News.

"There's enough oil in this country for another 100 years with our present technology and there's more around the world to be found yet."

Mr Holmes said that the average yield of the San Joaquin valley area was declining by about 8% a year but that new wells and new methods kept production viable.

New rush

The Monterey shale beneath California is estimated to contain a vast 15 billion barrels of oil - potentially worth $500bn (£330bn) - though there are uncertainties about whether the complex geology will allow easy extraction.

New extraction efforts are happening across a country once thought to be in oil-production decline

The prospect of a new oil rush has angered environmental campaigners, who argue that the focus should remain on a transition away from fossil fuels.

Kassie Siegel of the Centre for Biological Diversity said that "a rapid shift to clean energy" was needed to help tackle climate change, and that the mere existence of new oil resources did not mean that they had to be extracted and burned.

She told BBC News: "We need to win the battle against this big new oil boom in California - and we have to win it in California, where we pride ourselves on being a leader in responding to the climate crisis. Because if we can't win in California, where in the US can we win it?

"We're faced with a choice about what we're going to do with all this new oil - and we cannot burn this oil without lighting the fuse on a carbon bomb which would shatter our state's efforts to deal with greenhouse gas emissions."

Tom Frantz, an almond farmer and campaigner, has kept watch on the first fracking operations in the area of Shafter, near Bakersfield in California, as oil companies start exploring the potential of the Monterey shale.

"This is the tip of the iceberg with 70 wells," he told BBC News. "There could be 500 wells in the same area in three years if it's economical and this could extend north.

"Everybody in the path of this thing could be run over in a tidal wave of oil drilling and fracking and hazardous emissions."

None of the many companies operating in the area offered any comment when approached by the BBC. The issue remains highly controversial.

A key factor behind the development of new resources is the relatively high global price for oil. Extracting oil from "unconventional" sources such as "tight" rocks like shale costs more than from traditional reservoirs - and requires far more energy - so only becomes viable at certain price levels.

A paper published last week in Eos, external, the newsletter of the American Geophysical Union, supports the assertion that a peak in oil production is "a myth" but argues that the rising cost of extraction could itself provide a limit, and may act as a brake on economic growth.

Authors James Murray and Jim Hansen, questioning the optimism of energy companies, say production from unconventional sources often falls away rapidly. "The steep declines in production from tight oil wells over time require an ever-increasing treadmill of new drilling just to stay constant."

One leading industry figure summed up his view: "The era of cheap oil is over, but we're a long way from peak oil - costs will go up but then technology will respond."

It would appear the age of oil itself is far from over.

Watch David Shukman's report on BBC One's BBC News at Ten on Monday, 15 July at 22:00 BST (UK only).