Neutrino 'flavour' flip confirmed

- Published

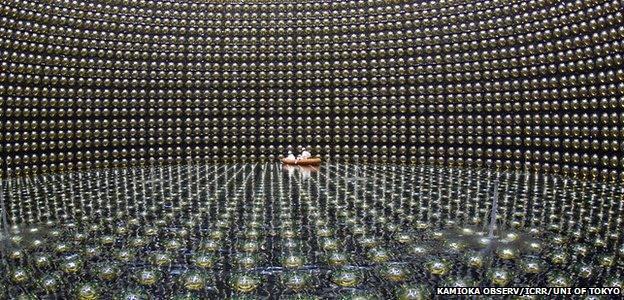

Super-K looks for the faint flashes of light emitted when passing neutrinos interact with its water

An important new discovery has been made in Japan about neutrinos.

These are the ghostly particles that flood the cosmos but which are extremely hard to detect and study.

Experiments have now established that one particular type, known as the muon "flavour", can flip to the electron type during flight.

The observation is noteworthy because it allows for the possibility that neutrinos and their anti-particle versions might behave differently.

If that is the case, it could be an explanation for why there is so much more matter than antimatter in the Universe.

Theorists say the counterparts would have been created in equal amounts at the Big Bang, and should have annihilated each other unless there was some significant element of asymmetry in play.

"The fact that we have matter in the Universe means there have to be laws of physics that aren't in our Standard Model, and neutrinos are one place they might be," Prof Dave Wark, of the UK's Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) and Oxford University, told BBC News.

The confirmation that muon flavour neutrinos can flip, or oscillate, to the electron variety comes from T2K, an international collaboration involving some 500 scientists.

The team works on a huge experimental set-up that is split across two sites separated by almost 300km.

At one end is the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Centre (J-Parc) located on the country's east coast.

It generates a beam of muon neutrinos that it fires under the ground towards the Super-Kamiokande facility on the west coast.

The Super-K, as it is sometimes called, is a tank of 50,000 tonnes of ultra-pure water surrounded by sensitive optical detectors.

These photomultiplier tubes pick up the very rare, very faint flashes of light emitted when passing neutrinos interact with the water.

In experiments in early 2011, the team saw an excess of electron neutrinos turning up at Super-K, suggesting the muon types had indeed changed flavour en route.

But just as the collaboration was about to verify its findings, the Great Tohoku Earthquake damaged key pieces of equipment and took T2K offline.

Months of repairs followed before the project was able then to gather more statistics and show the muon-electron oscillation to be a formal discovery.

Details are being reported on Friday at the European Physical Society Conference on High Energy Physics, external in Stockholm, Sweden.

"Up until now the oscillations have always been measured by watching the types disappear and then deducing that they had turned into another type. But in this instance, we observe muon neutrinos disappearing and we observe electron neutrinos arriving - and that's a first," said Prof Alfons Weber, another British collaborator on T2K from the STFC and Oxford.

Neutrino oscillations are governed by a matrix of three angles that can be thought of as the three axes of rotation in an aeroplane - roll, pitch and yaw.

Other research has already shown two of the matrix angles to have non-zero values. T2K's work confirms that the third angle - referred to as theta-one-three - also has to have a non-zero value.

This is critical because it allows for the oscillations of normal neutrinos and their anti-particles, anti-neutrinos, to be different - that they can have enough degrees of freedom to display an asymmetrical behaviour called charge parity (CP) violation.

CP-violation has already been observed in quarks, the elementary building blocks of the protons and neutrons that make up atoms, but it is a very small effect - too small to have driven the preference for matter over anti-matter after the Big Bang.

However, if neutrinos can also display the asymmetry - and especially if it was evident in the very massive neutrinos thought to have existed in the early Universe - this might help explain the matter-antimatter conundrum. The scientists must now go and look for it.

It is likely, though, that much more powerful neutrino laboratories than even T2K will be needed to investigate the issue.

"We have the idea for a Hyper-Kamiokande which will require an upgrade of the accelerator complex," Prof Weber told BBC News.

"And in America there's something called the LBNE, which again would have bigger detectors, more sensitive detectors and more intense beams, as well as a longer baseline to allow the neutrinos to travel further."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published15 May 2013

- Published5 July 2012

- Published30 March 2012

- Published15 June 2011

- Published23 September 2010