Dover's White Cliffs: Would you mine them for £1bn-worth of gold?

- Published

- comments

Could Dover's white cliffs be sold?

How do we decide what's worth saving and what we would happily see destroyed to make way for development? For The Editors, a programme which sets out to ask challenging questions, I asked what price, for example, for the White Cliffs of Dover?

Woven into the national fabric as a symbol of wartime defiance, the cliffs stand immortalised by the voice of Vera Lynn and images of soaring Spitfires.

A National Trust campaign has just raised over £1m to buy a key stretch of the cliff-tops to forestall any development.

Most people would probably agree that that was a good thing. The trust's campaign video flashed up names such as Caesar and Churchill to emphasise the pivotal importance of the cliffs to our island story, and the donations rolled in.

What makes the cliffs so distinctively white is that they are made of limestone. As it happens, this type of rock isn't particularly valued. You can buy a tonne of it for about £20.

But what if another kind of mineral was discovered inside the cliffs? Let's say, purely hypothetically, that the cliffs contain gold.

Now imagine that gleaming deposit of gold is valued at £10m. Would you agree to it being gouged out of the rock? Of course not. You'd say, "Don't be so grubby, didn't you learn any history at school?"

Upping the ante

But what if the gold was worth £1bn? At that price a few people might agree to let the diggers move in. After all, a new mine would create jobs and the Treasury would get another, very welcome, source of revenue. So would the National Trust.

There would be a protest movement, obviously, and I'm guessing that the majority would be outraged at the idea of sacrificing the cliffs for a mere billion. However, we would start to see a fracturing of public opinion, wouldn't we?

So let's up the ante. What if the deposit was in fact valued at £1tn? Yes, one trillion, almost the size of the national debt.

So what do you think now about demolishing a cherished corner of our national heritage?

Would you argue that times are exceptionally tough, that it is irresponsible not to make use of the gold, and that most visitors to Britain come by air so don't see the cliffs anyway.

You could suggest that a facade of the cliffs be maintained while the riches behind are burrowed out - it is £1tn, after all.

Or would you stiffen your spine, summon up the memory of Winston's call to fight invaders on the beaches and draw a principled line in the chalk? Some things, you could say, are just too precious. If the White Cliffs, why not Stonehenge? In short, is nothing sacred?

Rainforest threat

This idea came to me on an assignment in the heart of the Amazon rainforest.

The majestic ocean of green stretched for miles in all directions - and I'm sure I'm not alone in thinking that the world's largest tropical forest deserves special protection.

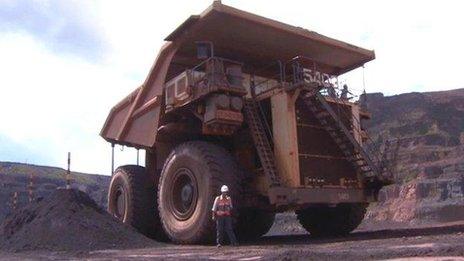

But right in the middle of the jungle, near the town of Carajas, is another feature that's the largest in the world - a vast iron-ore mine.

A huge iron-ore mine operates in the middle of the Amazon rainforest

The diggers work around the clock in unimaginably huge manmade canyons. The ore is shipped to the coast and on to the global markets.

We have probably all benefited from the iron of Carajas.

The metal ends up in our cars and bridges and office buildings. But each new extraction of the rock requires the destruction of another mass of trees.

The whole place is basically a mountain of iron. And its value? Getting on for $1tn. So, rainforest or iron?

I thought about these choices again while on a British research ship earlier this year.

The expedition was investigating the seabed off the Cayman Islands where hydrothermal vents - bizarre natural chimneys - rise from the ocean floor.

They host unique forms of life. And they're also richer than any rocks found on land.

The vents are brimming with copper and the rare earth minerals that all our electronics depend on. The seabed rocks are worth countless billions.

Suddenly, with metal prices so high, many areas of ocean floor all over the world are worth mining.

Prospecting is going on in about 20 areas. Huge robotic machines are being built to carve up the seabed. Excavating the rock could destroy marine life. But we all need the minerals.

Changing priorities

Attitudes vary. Wealth is one factor. Richer countries are more likely to feel able to afford conservation. Can Brazil, with its favelas, really turn down the money from its iron?

Necessity is another factor. The world is hungry for the metal that modern economies require - and is mining at sea really more damaging than mining on land?

A third point is that priorities change. When the Normans landed and conquered Britain in 1066, they built a massive castle on top of the White Cliffs. As victors, they didn't need planning permission.

Hydrothermal vents brim with rare minerals

When Napoleon massed his armies on the other side of the Channel, a huge fortress was built above Dover at the Western Heights. In the rush, no-one worried about demolishing an old Roman lighthouse that stood in the way.

Unloved, underfunded and mostly closed to the public, the fortress - the largest of its kind in England - is now set for a £5m makeover.

But the money comes as part of a deal - a development company provides the cash but in exchange wins the right to build a five-star hotel on the site and 500 homes in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty at Farthingloe nearby.

An unusual heritage landmark gets a new lease of life and Dover gets some badly needed investment.

How the re-developed fortress could look

But there is a price - paid by a stretch of countryside designated off-limits to development. So which is sacred - the fortress or the countryside? Where do we draw the line?

Back in the 1980s, there was widespread hostility to the building of the Channel Tunnel, including the difficult question of where the spoil would be dumped.

In the end it was tipped into the sea at the foot of the White Cliffs. At the time this seemed an appalling idea.

But the spoil formed a bank - which has now become the Samphire Hoe nature reserve visited by 100,000 people a year, a "bad" idea turned good.

Battles over how we use our land, and what we save and what we don't, will become tougher.

The population is growing and Britain is becoming more densely settled. The definition of what is sacred will become more contested.

Finally, in case you are wondering about that suggestion of gold in the White Cliffs? There isn't any. Just as well.

BBC News: The Editors features the BBC's on-air specialists asking questions which reveal deeper truths about their areas of expertise. Watch it on BBC One on Monday 29 July at 23:10 BST or catch it later on the BBC iPlayer or on BBC World News.