Alphasat: 'Space A380' ready for launch

- Published

- comments

Alphasat represents something close to £0.75bn in public and private investment

When, in 2007, the London Development Agency invested £12m in a new satellite project, there was consternation in certain British newspapers.

Why would the LDA do such a thing? What possible interest could London have in space?

The press concluded it had to be because the capital's then mayor, Ken Livingstone, wanted to spy on drivers - to fleece them of yet more cash on the back of the recently introduced congestion charge.

Six years later and that satellite is built and ready to go into orbit. Needless to say, it will not be tracking motorists.

Alphasat, as it is known, is the latest mission for one of London's - and the UK's - most successful space companies: Inmarsat.

The firm is the big daddy of global communications on the move. Its constellation of satellites enables people to stay in touch wherever they are. This means phone calls, internet connections and audio-visual material.

When you watch TV news crews filing reports from far-flung places, the video is very probably being fed over Inmarsat's network.

Ships, oil rigs and increasingly planes are major users of Inmarsat's services, as are the British armed forces.

Alphasat will fit seamlessly into the existing constellation, connecting customers in Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

But the spacecraft is rather special on a number of counts - something the LDA recognised, along with the development agencies of the South East (Seeda) and East of England (Eeda), who also each invested £12m in the project.

For one thing, it's rather large. It's based on a new chassis, or bus, that has been designed under the aegis of the European Space Agency (Esa) by Europe's two leading satellite manufacturers - Astrium and Thales Alenia Space. It will give the duo the ability to compete with US manufacturers at the top end of the market.

If you really wanted to, you could fill this new bus with payload and other equipment and hit the scales at nearly nine tonnes.

Mindful of another trans-Atlantic competition, Eric Beranger, who heads up Astrium's satellite production division, describes the new platform thus: "It is the A380 of the satellite world - there is nothing bigger."

Alphasat will not use every inch of this capacity. It will actually go to the launch pad at a nimble 6.5 tonnes. But its innards are still in the heavyweight class, particularly in terms of performance.

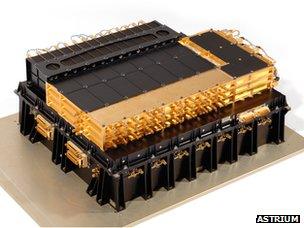

The satellite carries state-of-the-art digital signal processors - eight, in fact, each with 17 core computers all working in parallel. Together they can perform up to two trillion operations a second.

It's a remarkable set of kit which, allied to the satellite's smart 11m antenna/reflector system, can channel significant bandwidth and power on to specific locations on the ground at the drop of a hat.

That might be a war zone where large numbers of TV companies suddenly deploy reporting teams. It could also be a major earthquake where the terrestrial communications networks are disrupted and rescue workers need to coordinate a huge relief effort.

Inmarsat relays all this traffic over the L-band, a heavily congested part of the radio frequency spectrum. So, having the flexibility to switch this precious resource to where it's most needed, and use it in the most efficient way possible, is absolutely paramount.

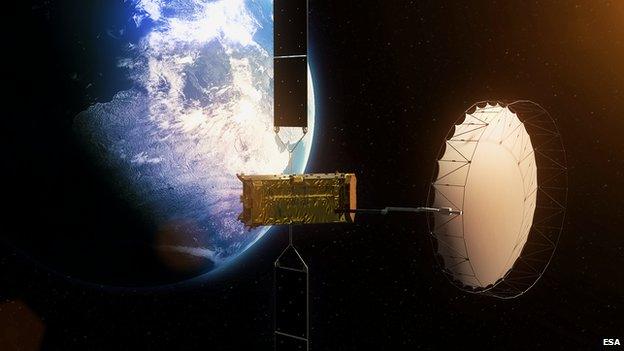

When Alphasat gets into orbit it must unfurl its solar panels and big antenna

And here's the nub of it for those far-sighted, but now defunct, regional development agencies in London and the South East.

Their investment ensured this technology was developed in the UK, designed at Astrium's base in Stevenage and built in Portsmouth. It's world-leading and will help keep the British satellite sector at the top of its game.

Overall, the Alphasat spacecraft represents something close to £0.75bn in value when you include all the public and private monies that have gone into its development across Europe.

Digital signal processor: The agile brain of Alphasat was designed and built in the UK

"We were very smart to put our investment into the digital processors," says Ruy Pinto, the chief technology officer at Inmarsat and the current chair of UKSpace, the UK space industry trade association.

"Yes, we could have built the bus, but that kind of technology is also in the US, in China, in Russia and India.

"It is better in my view to have the technology in the digital processors, to have the creative applications to generate jobs and wealth; to provide new ways that we can use our satellites - geo-location, climate change, Earth observation and mobile communications. Having that technology in Britain is a reason for all of us to be very proud."

On one level, Alphasat is very typical of the way UK public investments are made in space. Find a clever idea, pump prime it and then stand back and hope the commercial sector can multiply the effect.

It is an approach that has led Britain now to become the largest contributor to Esa's satellite telecommunications R&D programmes. These aim to de-risk the technologies European satellite companies need to stay competitive on the global stage.

"Alphasat is an example of the kind of investment we've been making in space in the UK quietly for a number of years. We're now trying to shout about it a bit more," says David Parker, the CEO of the UK Space Agency.

"When you look at Alphasat - this beast of a satellite - it is full of brilliant European technology and much of it is from the UK."