'Critical phase' for Iter fusion dream

- Published

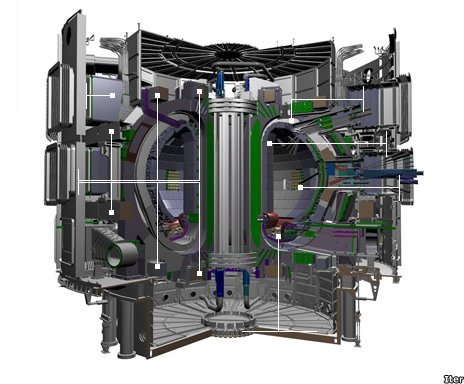

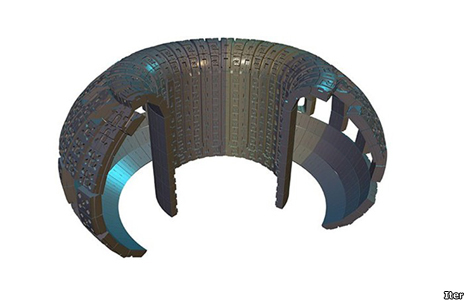

The foundations for Iter's tokamak - which will contain the hot plasma - have been laid

The world's largest bid to harness the power of fusion has entered a "critical" phase in southern France.

The Iter project at Cadarache in Provence is receiving the first of about one million components for its experimental reactor.

Dogged by massive cost rises and long delays, building work is currently nearly two years behind schedule.

The construction of the key building has even been altered to allow for the late delivery of key components.

"We're not hiding anything - it's incredibly frustrating," David Campbell, a deputy director, told BBC News.

"Now we're doing everything we can to recover as much time as possible.

"The project is inspiring enough to give you the energy to carry on - we'd all like to see fusion energy as soon as possible."

After initial design problems and early difficulties co-ordinating this unique international project, there is now more confidence about the timetable.

Since the 1950s, fusion has offered the dream of almost limitless energy - copying the fireball process that powers the Sun - fuelled by two readily available forms of hydrogen.

The attraction is a combination of cheap fuel, relatively little radioactive waste and no emissions of greenhouse gases.

But the technical challenges of not only handling such an extreme process but also designing ways of extracting energy from it have always been immense.

In fact, fusion has long been described as so difficult to achieve that it's always been touted as being "30 years away".

Now the Iter reactor will put that to the test. Known as a "tokamak", it is based on the design of Jet, a European pilot project at Culham in Oxfordshire.

It will involve creating a plasma of superheated gas reaching temperatures of more than 200 million C - conditions hot enough to force deuterium and tritium atoms to fuse together and release energy.

The whole process will take place inside a giant magnetic field in the shape of a ring - the only way such extreme heat can be contained.

The plant at JET has managed to achieve fusion reactions in very short bursts but required the use of more power than it was able to produce.

The reactor at Iter is on a much larger scale and is designed to generate 10 times more power - 500 MW - than it will consume.

France's fusion reactor would work like the sun

Iter brings together the scientific and political weight of governments representing more than half the world's population - including the European Union, which is supporting nearly half the cost of the project, together with China, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States.

Contributions are mainly "in kind" rather than in cash with, for example, the EU providing all the buildings and infrastructure - which is why an exact figure for cost is not available. The rough overall budget is described as £13bn or 15bn euros.

But the novel structure of Iter has itself caused friction and delays, especially in the early days.

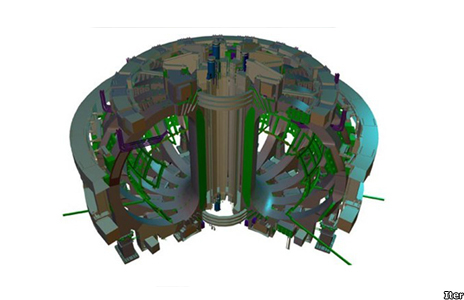

Cryostat

The cryostat holds the vacuum vessel and acts as a giant fridge maintaining the low temperature needed for the superconducting magnets.

Magnets

The magnet system confines and controls the plasma inside the vacuum vessel and will generate a magnetic field 200,000 times higher than the Earth.

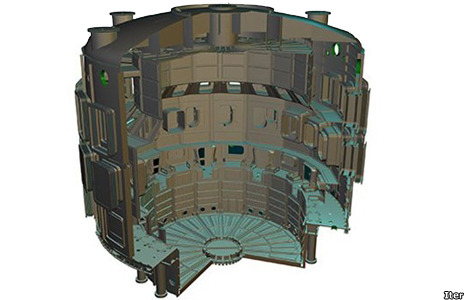

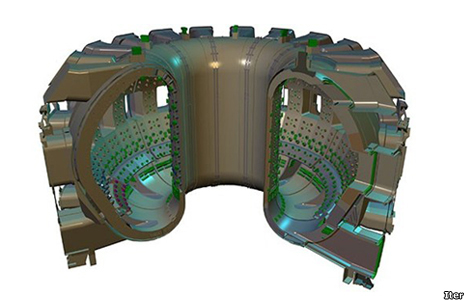

Vacuum

The vacuum vessel is a doughnut-shaped chamber in which the fusion reaction takes place as the plasma particles spiral continuously without touching the walls.

Blanket

The blanket covers the interior surfaces of the vacuum vessel, shielding the vessel and superconducting magnets from the heat and high-energy neutrons produced by the fusion reaction.

Divertor

The divertor sits at the bottom of the vacuum vessel and acts like an exhaust system, extracting heat and helium ash and other impurities from the plasma.

Heaters

For the gas in the vacuum chamber to become plasma, the temperatures inside the reactor need to reach 150 million degrees celsius—or ten times the temperature of the centre of the Sun.

Each partner first had to set up a domestic "agency" to handle the procurement of components within each member country, and there have been complications with import duties and taxes.

Further delay crept in with disputes over access to manufacturing sites in partner countries. Because each part has to meet extremely high specifications, inspectors from Iter and the French nuclear authorities have had to negotiate visits to companies not used to outside scrutiny.

The result is that although a timeline for the delivery of the key elements has been agreed, there's a recognition that more hold-ups are almost inevitable.

The main building to house the tokamak has been adjusted to leave gaps in its sides so that late components can be added without too much disruption.

The route from the ports to the construction site has had to be improved to handle huge components weighing up to 600 tonnes, but this work too has been slower than hoped. A trial convoy originally scheduled for last January has slipped to this coming September.

Preparation work at the Iter site in Cadarache began in 2007. Some 90 hectares has been cleared and levelled for scientific buildings and facilities, leaving the other half of the site in its original wooded state

Here, construction teams work on the foundations for Iter's Tokamak complex. Begun in 2011, the works require about 110,000 cubic metres of concrete and some 3,400 tonnes of steel reinforcement

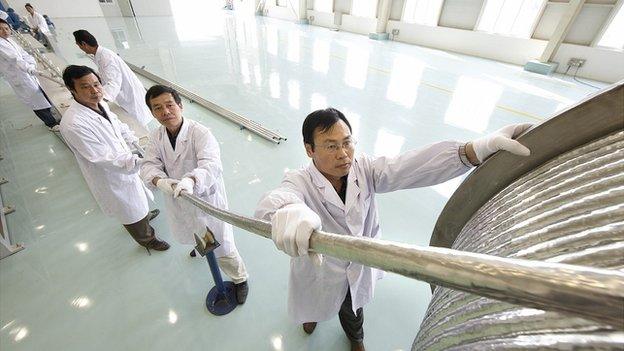

A 12,000 sq m building will be used to assemble the giant poloidal field (PF) coils - part of the magnetic system that helps control plasma inside Iter's vacuum vessel. The 40-tonne circular spreader beam (pictured) can travel the length of the building to move components around

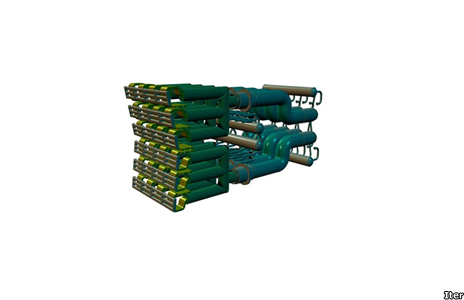

Manufacturing is underway on many components destined for the facility. This picture shows a prototype for stainless steel plates that will hold part of the toroidal field coil system

The field coils use special cable that is "superconducting", meaning it can conduct electricity with zero resistance as well as generating intense magnetic fields. In order to become superconducting, the coils have to be cooled with helium to -269C

Under an initial plan, it had once been hoped to achieve the first plasma by the middle of the last decade.

Then, after a redesign, a new deadline of November 2020 was set but that too is now in doubt. Managers say they are doubling shifts to accelerate the pace of construction. It's thought that even a start date during 2021 may be challenging.

The man in charge of coordinating the assembly of the reactor is Ken Blackler.

"We've now started for real," he told me. "Industrial manufacturing is now under way so the timescale is much more certain - many technical challenges have been solved.

"But Iter is incredibly complicated. The pieces are being made all around the world - they'll be shipped here.

"We'll have to orchestrate their arrival and build them step by step so everything will have to arrive in the right order - it's really a critical point."

Command and control

While one major concern is the arrival sequence of major components, another is that the components themselves are of sufficiently high quality for the system to function.

The 28 magnets that will create the field containing the plasma have to be machined to a very demanding level of accuracy. And each part must be structurally sound and then welded together to ensure a totally tight vacuum - without which the plasma cannot be maintained. A single fault or weakness could jeopardise the entire project.

Assuming Iter does succeed in proving that fusion can produce more power than it consumes, the next step will be for the international partners to follow up with a technology demonstration project - a test-bed for the components and systems needed for a commercial reactor.

Ironically, the greater the progress, the more apparent becomes the scale of the challenge of devising a fusion reactor that will be ready for market.

At a conference in Belgium last September, I asked a panel of experts when the first commercially-available fusion reactor might generate power for the grid.

A few said that could happen within 40 years but most said it would take another 50 or even 60 years. The fusion dream has never been worked on so vigorously. But turning it into reality is much more than 30 years away.