Secret of Usain Bolt's speed unveiled

- Published

Bolt's 2012 Olympic record of 9.63 seconds in the 100m final was not his fastest 100m sprint

Scientists say they can explain Usain Bolt's extraordinary speed with a mathematical model.

His 100m time of 9.58 seconds during the 2009 World Championships in Berlin is the current world record.

They say their model explains the power and energy he had to expend to overcome drag caused by air resistance, made stronger by his frame of 6ft 5in.

Writing in the European Journal of Physics, external, the team hope to discover what makes extraordinary athletes so fast.

According to the mathematical model proposed, Bolt's time of 9.58 seconds in Berlin was achieved by reaching a speed of 12.2 metres per second, equivalent to about 27mph.

Less dynamic

The team calculated that Bolt's maximum power occurred when he was less than one second into the race and was only at half his maximum speed. This demonstrates the near immediate effect of drag, which is where air resistance slows moving objects.

They also discovered less than 8% of the energy his muscles produced was used for motion, with the rest absorbed by drag.

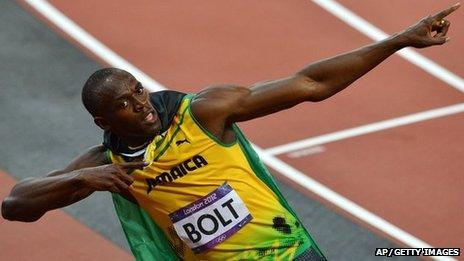

The 2012 gold medallist became a worldwide sensation

When comparing Bolt's body mass, the altitude of the track and the air temperature, they found out that his drag coefficient - which is a measure of the drag per unit area of mass - was actually less aerodynamic than that of the average man.

Effects of drag

Jorge Hernandez of the the National Autonomous University of Mexico said: "Our calculated drag coefficient highlights the outstanding ability of Bolt. He has been able to break several records despite not being as aerodynamic as a human can be.

"The enormous amount of work that Bolt developed in 2009, and the amount that was absorbed by drag, is truly extraordinary.

"It is so hard to break records nowadays, even by hundredths of a second, as the runners must act very powerfully against a tremendous force which increases massively with each bit of additional speed they are able to develop.

"This is all because of the 'physical barrier' imposed by the conditions on Earth. Of course, if Bolt were to run on a planet with a much less dense atmosphere, he could achieve records of fantastic proportions.

"The accurate recording of Bolt's position and speed during the race provided a splendid opportunity for us to study the effects of drag on a sprinter.

"If more data become available in the future, it would be interesting to see what distinguishes one athlete from another," added Mr Hernandez.

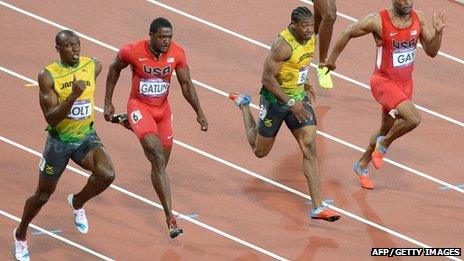

Bolt (L) is known to be a slow starter

Bolt's time in Berlin was the biggest improvement in the record since electronic timing was introduced in 1968.

Large stride

John Barrow at Cambridge University who has previously analysed how Bolt could become even faster, explained that his speed came in part due his "extraordinary large stride length", despite having such an initial slow reaction time to the starting gun.

"He has lots of fast twitch muscle fibres that can respond quickly, coupled with his vast stride is what gives him such an extraordinary fast time."

He said Bolt has lots of scope to break his record if he responded faster at the start, ran with a slightly stronger tail-wind and at a higher altitude, where there was less drag.

Bolt's Berlin record was won with a tail wind of only 0.9m per second, which didn't give him "the advantage of helpful wind assistance", he added.

"You're allowed to have a wind no greater than 2m per second to count for record purposes, so without becoming any faster he has huge scope to improve," Prof Barrow told BBC News.