Gravity controls icy moon Enceladus's spew

- Published

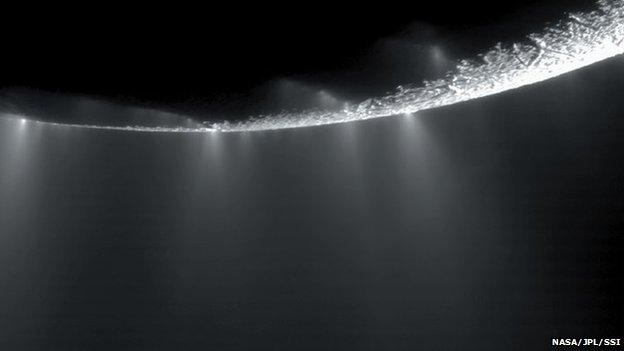

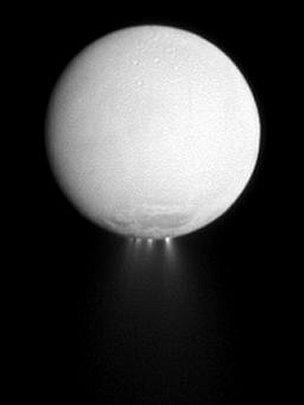

Fountains of water ice are blasted thousands of kilometres above the surface of Saturn's tiny moon Enceladus

Saturn's gravitational pull is responsible for the extraordinary hot geysers on the Enceladus moon that spew water out into space.

The particles are ejected from active fissures known as "tiger stripes" at Enceladus's south pole.

Salt in the plumes suggest the water may come from a liquid ocean beneath its icy shell.

But it had been unclear what was ultimately driving the geological activity on this moon.

Writing in Nature, external, a team observed that its southern plume was four times brighter when Enceladus was furthest from Saturn.

Enceladus orbits around Saturn in a distorted, elliptical shape rather than a circular one. This causes the moon to be pulled and squeezed by Saturn's gravity, which heats its interior and enables geological activity on the icy moon.

In 2005 scientists discovered that the surface of this 500km-wide moon was geologically active. Since then they have looked to confirm how Saturn influences the stresses on its surface.

Now a team has tracked the activity of Enceladus through its orbit by analysing 252 images from the Cassini spacecraft, controlling for factors that affect its brightness.

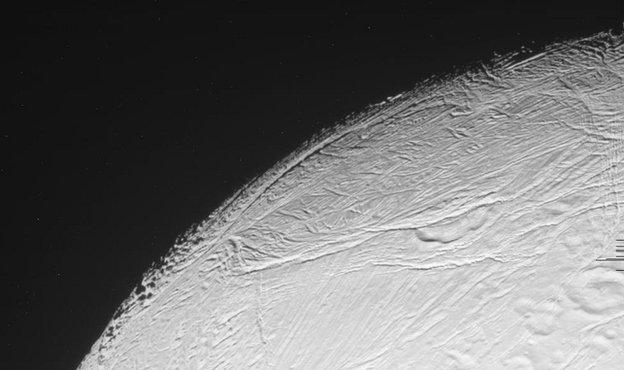

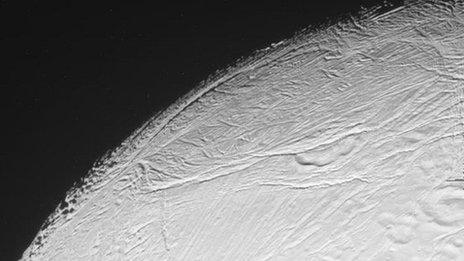

Abundant evidence of geological activity criss-crosses Enceladus's surface

Led by Matthew Hedman at Cornell University, US, the researchers looked at whether the intensity of the plumes from Enceladus's south pole was changing.

When Enceladus went around its slightly elliptical orbit, "the plume was much brighter when it was furthest from Saturn, than when it was closest to the planet", explained Dr Hedman.

He added: "What this tells us is that Saturn's tides are having a significant effect on how much material can escape from beneath Enceladus.

"Previous models predicted that when Enceladus was near the point most distant from Saturn, the cracks would be pulled open or widened, and the most amount of liquid would escape. This is the first observational data we have that shows quite clearly that is the case."

Habitable environment

He explained that how much the moon responded to these tidal forces could give insight into the "rigidity of its interior" which could help scientists discover what's going on beneath its surface, and where the water vapour and ice streams came from.

"Nobody fully understands why Enceladus is geologically active, but this plume has interesting potential applications for trying to understand what could be a habitable environment," Dr Hedman addded.

Scientists believe Enceladus could be habitable

Nasa planetary scientist Terry Hurford, who first made tidal stress predictions about Enceladus's cracks in 2007, said it was a great piece of work that "ties the story together" of how the stresses on its surface were formed.

He said there were "big questions" about Enceladus and whether it had a liquid ocean.

"On the model I used to predict this variability in the stresses, I assume there's a global ocean. I think since the current observations are in line with the prediction it might be evidence of a global ocean and not just a local sea.

"Anywhere you have liquid water, there's a chance it could be habitable. What's even more exciting is that because of the material on the surface, you could sample what's in the liquid to learn more about it, unlike Europa which has a few kilometres of ice on top of its ocean," Dr Hurford told BBC News.

In an accompanying news and views article, external, John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute, US, said that Enceladus was one of the few places beyond Earth "where we can watch geology happen in real time, giving us a primer for understanding other, less active, icy worlds".

"The likely presence of liquid water and complex organic chemistry makes Enceladus especially intriguing as a potential habitat for extraterrestrial life, providing additional motivation for investigating its interior."

- Published29 March 2012

- Published20 March 2012