Can virtual reality be used to tackle racism?

- Published

WATCH: How VR might help to raise awareness of racism

It's an uncomfortable truth but scientists say most people have an ingrained racial bias. Now a team has shown that a short stint in a virtual world could reduce it, but could this have a longer lasting effect?

Racism is an issue that still pervades many societies.

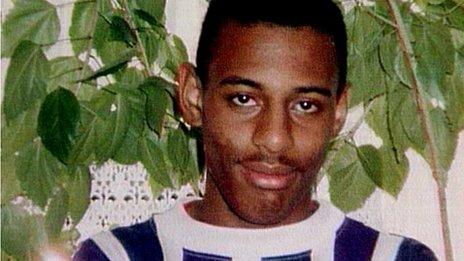

In England and Wales, there have been 106 fatal racist attacks since the killing of teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993 according to the Institute of Race Relations, external. It also reports thousands of racist incidents recorded by the police each year.

The issue is complicated by the fact that many biases are ingrained over long periods of time.

Scientists have now found that this ingrained racial bias was reduced when participants were immersed in a virtual body of a different race.

To test their implicit racism, a team led by Mel Slater at the University of Barcelona gave participants what's called an implicit association test several days before the experiment. They were given the same test again after their experience in virtual reality.

It was only the participants who had been placed in a dark virtual body that showed this decrease.

Another unrelated study had similar results. A team found that when a dark rubber hand was stroked at the same time as the participant's own (out of sight) hand was touched, implicit racism subsequently decreased. This work was led by Manos Tsakiris at Royal Holloway University of London.

Both teams say it's promising that two separate experimental settings show this effect.

Participants' body movements were tracked using a motion-capture suit

It might be surprising to some white people that they show preference for white faces over black faces in the implicit test. This could be for a number of reasons, says Prof Slater.

It doesn't mean someone is explicitly racist, he says, rather it reflects how their brain has been wired based on the society in which they grew up.

If the media frequently reports negatively on a given "out-group", for example, then somehow the brain picks up these associations which are reproduced in the implicit bias test.

Stroking a black rubber hand reduced a participant's implicit racism score

He refers to virtual reality as an "empathy generating machine" to give people experiences they can't have in any other way.

The question remains whether or not these findings could ever be applied in the real world.

Prof Slater believes they could: "If the effect is shown to be long-lasting this might provide tools for serious immersive games that attempt to foster pro-social behaviour and empathy," he argues.

Prof Tsakiris agrees. He believes that achieving similar results could even be possible without an experimental set-up.

"It's about the idea of sharing sensory experiences with people that might be different from you. This sharing - especially when there is some kind of synchronicity between people's bodies - it can bring people closer together.

"Doing things with others seems to function as a social glue. The obvious thing would be to have no segregation in society, not to have any schools dominated by one ethnic group," Prof Tsakiris adds.

It is still unclear how long-lasting these effects would be. Prof Slater says this will be hard to pin down, but rolling the technology out into the real world in the first instance is a possibility.

"It may be used to help people who have these implicit biases, to recognise they have them but also to reduce them."

But Antony Greenwald, at the University of Washington in Seattle, says it's still too early to be optimistic because the negative associations measured by the implicit racism test "are pretty durable".

"The best interpretation is that this makes some sort of temporary change in how a person represents the categories [of race].

"We live in a world in which we are surrounded by things that cause us to develop associations that produce stereotypes. It's like the air we breathe; we can't help talking it in," Prof Greenwald adds.

However, Ziada Ayorech, from King's College London says the research shows that a negative racial bias could be detuned over time and could even become positive.

"When we think of something as implicit racial bias you think that it's already ingrained and there's nothing you can do, but in reality these studies show that by simply having people relate to someone with a different ethnicity - you can already change that.

"New associations will be built. It's a stepping stone, for sure."

But outside an experimental setting, tackling ingrained racism remains difficult, especially because it's hidden, says Neil Chakraborti, a criminologist at the University of Leicester who works with victims of racist attacks.

"Precisely because it is almost impossible to label it as an offence, latent racism is rarely reported. You see people normalise these kinds of experiences; it's become a routine part of being different," he says.

This issue of prejudice is something Dal Babu feels he has experienced in the police force - an organisation he says should be representative of the society it aims to protect.

He was one of the UK's top ethnic minority officers at the Metropolitan Police, and was critical of the lack of black and Asian recruits and how few were in senior positions.

"The irony and most commonly quoted phrase by Sir Robert Peel (founder of the Met Police) is that the public are the police and the police are the public," he says.

But despite his efforts, the majority of senior police officers "remain stubbornly white", Mr Babu adds.

It's clear that there is no one simple way to tackle an issue as complex as racism. Until researchers find that reducing an innate bias can be reproduced and sustained, an awareness of it seems a crucial first step.

And while its use outside the lab may be some way off, scientists say that virtual reality provides a stepping stone towards increased empathy with others in the real world.

Watch a longer report on BBC Click. If you are in the UK, you can watch the whole programme on the BBC iPlayer from Saturday 30 November.

- Published21 November 2013

- Published8 November 2013

.jpg)

- Published28 August 2013

- Published18 August 2013

- Published27 March 2012

- Published20 March 2012

- Published6 January 2012