Global warming slowdown linked to cooler Pacific waters

- Published

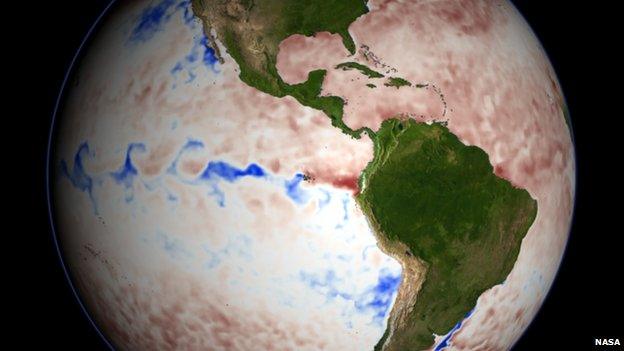

Cooler waters in the equatorial Pacific are linked to cyclical events such as La Nina

Scientists say the slow down in global warming since 1998 can be explained by a natural cooling in part of the Pacific ocean.

Although they cover just 8% of the Earth, these colder waters counteracted some of the effect of increased carbon dioxide say the researchers.

But temperatures will rise again when the Pacific swings back to a warmer state, they argue.

The research is published, external in the journal Nature.

Climate sceptics and some scientists have argued that since 1998, there has been no significant global warming despite ever increasing amounts of carbon dioxide being emitted.

For supporters of the idea that man made emissions are driving up temperatures, the pause has become increasingly difficult, external to ignore.

Scientists have tried to explain it using a number of different theories but so far there is no general agreement on the cause.

"For people on the street it is very confusing as to which story is closer to the truth," lead author, Prof Shang-Ping Xie from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography told BBC News.

"We felt a similar contradiction and that's why we started doing these modelling studies."

Cooling the carbon

Prof Xie said there were two possible reasons why the continuing flow of CO2 has not driven the mercury higher.

The first is that water vapour, soot and other aerosols in the atmosphere have reflected sunlight back into space and thereby had a cooling effect on the Earth.

The second is natural variability in the climate, especially the impact of cooling waters in the tropical Pacific ocean.

Although it only covers 8.2% of the planet, the region is sometimes called the engine room of the world's climate system and atmospheric circulation.

Drought conditions in the southern US were predicted by the model

Researchers already know that a naturally occurring cycle in this area, called the El Nino-Southern Oscillation, external, has a major impact on global climate.

But Prof Xie and colleagues were interested in a different cycle called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, external that lasts for a much longer period of time.

To test his theory, Prof Xie and his colleagues developed a dynamic climate model that measured the greenhouse effect on temperatures but also included records of sea surface temperatures in this region of the eastern Pacific.

"Previous efforts using climate models take radiative forcing as the only input, externally, and they produce a temperature record close to observations except for the past 15 years," said Prof Xie.

"Only when we input equatorial Pacific ocean temperatures into our model, were we able to reproduce the flattening of the temperature record."

Swing continues

This model also explains some of the other contradictions seen since temperatures flat lined.

There have been major heat waves in Europe in 2003, Russia in 2010, external and in the US in 2012.

Arctic sea ice also dropped to its lowest recorded level in 2012. All these are indications that the climate is continuing to warm, but the global average temperature has remained below the figure for 1998.

"The solution to this contradiction is that temperature has behaved differently between winter and summer seasons," said Prof Xie.

"The influence of the equatorial Pacific ocean is strongest in winter but weakest during the summer, so CO2 can keep working on the temperature and sea ice in the Arctic over the summer."

Flowers growing in Greenland as temperatures rise indicating that global warming is having real impacts

The last time the Pacific was in a relatively cold state was in the 30 year period from the 1940s to 1970s said Prof Xie and that coincides with the last hiatus in climate warming.

But the researchers warn that the impact of this multi-decadal cool trend will come to an end and will be replaced by a warming one. Global temperatures will rise once again.

"We're pretty confident that the swing up will come some time in the future, but the current science can't predict when that will be," said Prof Xie.

Other scientists have welcomed the study saying it offers a coherent explanation of the slowdown.

"The new simulation accurately reproduces the timing and pattern of changes that have occurred over the last four decades with remarkable skill, " said Dr Alex Sen Gupta from the University of New South Wales.

"This clearly shows that the recent slowdown is a consequence of a natural oscillation."

Other researchers believe the new work supports the idea that the heat in the atmosphere has gone into the oceans.

"This new study adds further evidence that the recent slowdown in the rate of global warming at the Earth's surface is explained by natural fluctuations in the ocean and is therefore likely to be a temporary respite from warming in response to rising concentrations of greenhouse gases," said Dr Richard Allan from the University of Reading.

Dr Will Hobbs from Australia's Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies agrees.

He said: "Over the period that the authors analysed, observations showed a continued trapping of heat in the Earth's climate system, despite the temporary slowdown in surface warming, and an important question that the paper does not address is where this energy has gone.

"Almost certainly it is in the deep ocean."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external.

- Published19 May 2013

- Published22 July 2013

- Published19 August 2013