Bullied mice overcome anxiety after light treatment

- Published

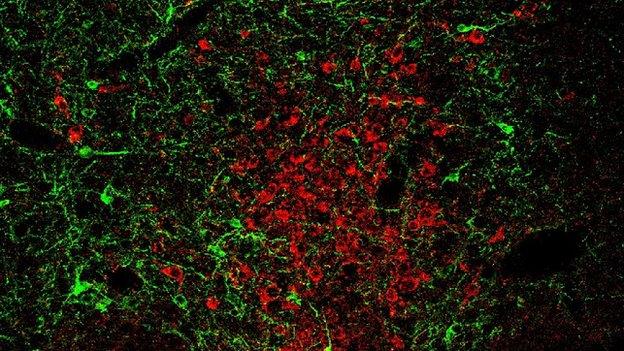

Neurons were found (green) which inhibited the release of serotonin (red)

Scientists have discovered the neurons that can lead mice to become socially anxious when they are bullied.

These neurons inhibit the release of serotonin, the deficiency of which is linked to social disorders.

The team was able to "switch off" these neurons which made the mice resilient to bullying.

The work is published in the Journal of Neuroscience, external, and could give insight into how similar structures in humans function.

Olivier Berton at the University of Pennsylvania medical school, US, said his paper provided a novel understanding at the cellular level, of how social defensiveness developed in a mouse.

Dr Berton and colleagues exposed 54 mice to negative social experiences from aggressive, territorial mice and found that more than half were defeated by bullies, which made them anxious.

The neurons responsible for emitting serotonin consequently became less responsive.

Resilient mice

The team identified that a class of GABA neurons (gamma aminobutyric acid - the neurotransmitters which inhibit other cells) were next to the neurons which released serotonin.

It was these GABA neurons that were putting a "brake" on the serotonin being released.

Using optogenetics, a technique which can make individual neurons respond to light, the team was able to switch off these neighbouring GABA neurons which made the mice resilient to bullying.

After the GABA neurons had been deactivated, it changed the way mice perceived a social threat and therefore prevented them becoming socially anxious.

"We are removing the brake from serotonin neurons and they are then able to fire normally," explained Dr Berton.

The team was able to switch off neurons using a technique called optogenetics

Finding the function of these GABA neurons could now help scientists understand why current antidepressants do not work for everyone and targeting these neurons could improve medication, he added.

"It could help us understand the basis of similar social symptoms in human pathologies, like social phobias and depression."

Dr Berton explained that while there has been much progress made indentifying regions of the brain involved in social disorders, more needs to be done to learn about the cellular level of the brain.

"This work may give us a stepping stone to extrapolate about how this is happening in the human brain," he told BBC News.

Lynn Kerby of the Temple University School of Medicine, Philadephia, US, was not involved with the research.

She said the study could give "significant insight" into the behaviours that contributed to social stress in humans.

"If there was a way to control these circuits in the human brain with the cellular precision used in the mice in this study, the results suggest that we might be able to promote adaptive behavioural responses to stress.

"Though exciting to imagine, whether such manipulations will ever be available or practical for use to treat human psychiatric diseases in the future, remains to be seen."

- Published25 July 2013

- Published27 November 2012

- Published23 March 2011