Volcanic sleeping giant opens North Korean co-operation

- Published

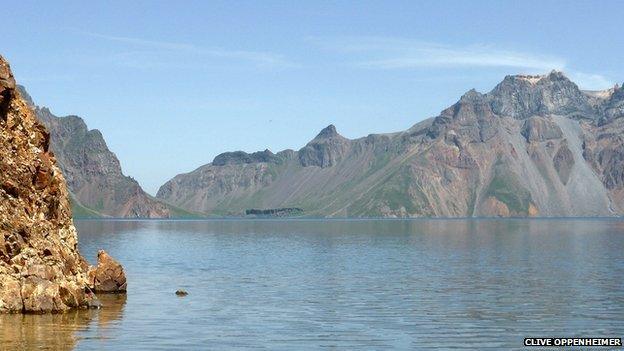

A crater lake at the summit threatens to create dangerous mud flows in the event of an eruption

Scientists from the UK, US and North Korea have joined forces to monitor the volcano responsible for one of the largest eruptions in history.

The volcano straddles the border between North Korea and China, and has been largely dormant since erupting a little over a thousand years ago.

Despite being at the top of the list of big eruptions, Mount Paektu remains obscure and enigmatic.

Details of the collaborative effort have been outlined in Science journal.

The international group of geologists has begun working on the volcano following a spate of recent earthquake activity that could indicate it is waking from slumber.

Surprisingly, the volcano is relatively unknown in the West, not helped by the fact that it takes a confusing array of names. In China it is known variously as Tianchi or Changbaishan, but its Korean name is Baegdu-san or Mount Paektu, while the Japanese call it Hakuto-san.

Around two thirds of the volcano lies in North Korea, with the remainder is in Chinese territory, and an estimated 30,000 tourists visit its Chinese flank each day, around twice the number visiting Mount Fuji in Japan.

In 940 AD, the volcano exploded in a huge eruption, known as the "millennium eruption" that threw ash vast distances. Measurements of ash deposits from that eruption measured in Japan indicate that this was one of the two largest known volcanic eruptions on Earth since that period, matched only by the Tambora eruption in Indonesia, in 1815 AD.

Dr James Hammond from Imperial College London, and Prof Clive Oppenheimer from the University of Cambridge have begun a collaborative study with North Korean scientists, aiming to understand the structure of the subterranean magma chamber lying beneath the volcanic mountain.

Explaining the origins of the project, Dr Hammond told BBC News: "The whole region is quite worried about the volcano because it has shown signs of activity, so the North Koreans put a lot of effort into watching it, and basically said 'do you want to come to Korea, could you bring some equipment?'"

UK seismometers, deployed on the volcano's flanks, will reveal its structure and activity

The team has deployed a set of seismometers that can record earth tremors associated with the movement of magma beneath the volcano.

Organising a scientific collaboration in North Korea has not been without logistical and bureaucratic hurdles, but Dr Hammond continued: "What made it possible was having great people involved who were passionate about doing this, at all levels, from the scientists on the ground to those higher up where the decisions get made."

The study will help scientists understand why the volcano is there, which is something of a geological mystery, and why rock is melting at its heart, possibly stoking a future threat.

"This project is not about monitoring the volcano or predicting when the eruption will happen, but is about understanding what happened during the millennium eruption and also looking at what its state is now, using geophysical techniques. This will help us understand what is driving the volcano," Dr Hammond explained.

Prof James Gill, from University of California, Santa Cruz, has been working on the Chinese side of the volcano for some years, but is not involved in the new study. He told BBC News: "The volcano has erupted big time in the past, and were it to happen again, the Chinese, South Korean and Japanese economies could all be affected.

"There was a crisis in 2002-2005 when the seismicity picked up, the gas chemistry of the fumaroles changed, the volcano inflated, and it might have erupted. It may still be dangerous.

"The North Korean underground nuclear test site is only 70km or so away, so when the last test took place, the South Koreans were concerned that this might set off the volcano.

"One of the world's biggest volcanoes is sat in a backwater of the Cold War."

Prof Gill described some of the difficulties of carrying out field work at a militarised border, sampling rocks under armed escort. The new collaboration with the North Koreans is something of a landmark in current scientific co-operation with the isolated state.

This is not the only volcano that Prof Oppenheimer and Dr Hammond have worked on in difficult circumstances. They have previously studied volcanoes that straddle the border of Eritrea and Ethiopia. Like Mount Paektu, that investigation also ran into challenges due to the local political situation, but underlines the fact that natural hazards pay no attention to political differences.

- Published15 July 2013

- Published6 July 2013

- Published28 June 2013