'Ancient humans' used toothpicks

- Published

"Ancient humans" used toothpicks nearly 1.8 million years ago, a study of their teeth has revealed.

A team studied hominid jaws from the Dmanisi Republic of Georgia - the earliest evidence of primitive humans outside Africa.

They also found evidence of gum disease caused by repeated use of what must have been a basic toothpick.

Writing in PNAS,, external the team says its findings help to explain the diversity found in hominid teeth.

The researchers used a new forensic approach to look at variations on the teeth of hominids thought by some to be early European ancestors.

Teeth can shed light on what the individuals ate and how old they may have been, but until now it was not clear why there was so much diversity in the Georgian hominid mandibles, or jaws.

Ani Margvelashvili, lead author of the study at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, said that scientists dealing with fossil hominid mandibles should pay close attention to tooth wear and the fossil individual's age.

"Progressive tooth wear triggers bone remodelling processes that substantially modify the shape of the jaw during an individual's lifetime. These effects are typically underestimated when attributing fossil hominid jaws to different species," she told BBC News.

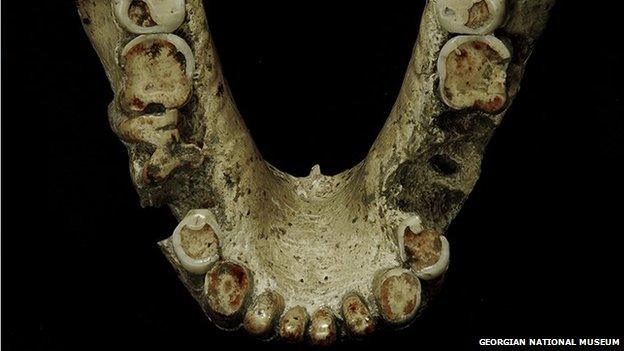

"The individual who was using a toothpick was young, as his or her teeth were not worn down. We also discovered a damaged area between the tooth area and the gum. There was a small cylinder-shaped lesion - in this area, if you place a toothpick it goes through."

The researchers analysed four mandibles from one of the biggest collections of well-preserved early human remnants known anywhere in the world.

The Dmanisi site has been valued as an important place to look at how hominids migrated from Africa.

"It's not very often you have one site with four mandibles. It has allowed us to see special features that have not been seen before," explained David Lordkipanidze of the Georgian National Museum.

This included horizontal scratches on a lesion, visible on the root surface of one of the teeth.

"Scientists often describe groups with new characters as different species. Here we show in one group you can see many characteristics. It shows once more how complicated the story of human evolution is," Prof Lordkipanidze, co-author of the work, told BBC News.

A toothpick perfectly fit through a cylinder shaped lesion

It is still unclear what species the Dmanisi hominids were. Experts once believed it was Homo erectus who first ventured out of Africa.

But the Dmanisi hominids were not typical of the tall-standing and big-brained H. erectus. Instead, the Dmanisi individuals were short, long-armed, small-brained and thin browed. The fossils are therefore now sometimes referred to as Homo georgicus.

Louise Humphrey from the Natural History Museum, London, said there had been a longstanding interest in the causes and implications of the high degree of variation in their mandibles and crania.

"This paper demonstrates that remodelling of the mandible associated with heavy tooth wear and continuous tooth eruption could contribute to that variation."

Peter Ungar from the University of Arkansas, US, said the study could provide a new way of looking at fossils.

"Tooth pick markings are not uncommon in fossil hominids from this time period, but this clinical, forensic approach is new and potentially useful.

"Analyses of tooth movements due to wear have been more-or-less limited to anatomically modern humans, and this paper introduces the approach to paleoanthropology," Prof Ungar added.

The mandibles that showed the least wear were from younger individuals

- Published4 June 2013