Computer chemists win Nobel prize

- Published

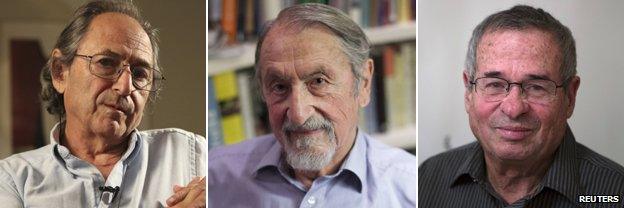

The work of Levitt, Karplus and Warshel has spawned a worldwide industry

The Nobel Prize in chemistry has gone to three scientists who "took the chemical experiment into cyberspace".

Michael Levitt, a British-US citizen of Stanford University; US-Austrian Martin Karplus of Strasbourg University; and US-Israeli Arieh Warshel of the University of Southern California will share the prize.

The trio devised computer simulations to understand chemical processes.

In doing so, they laid the foundations for new kinds of pharmaceuticals.

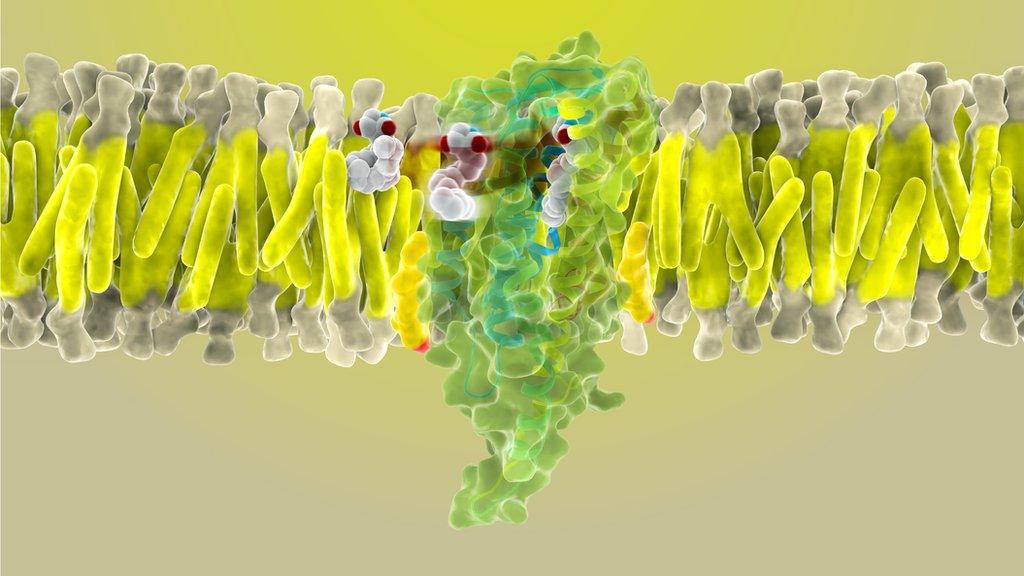

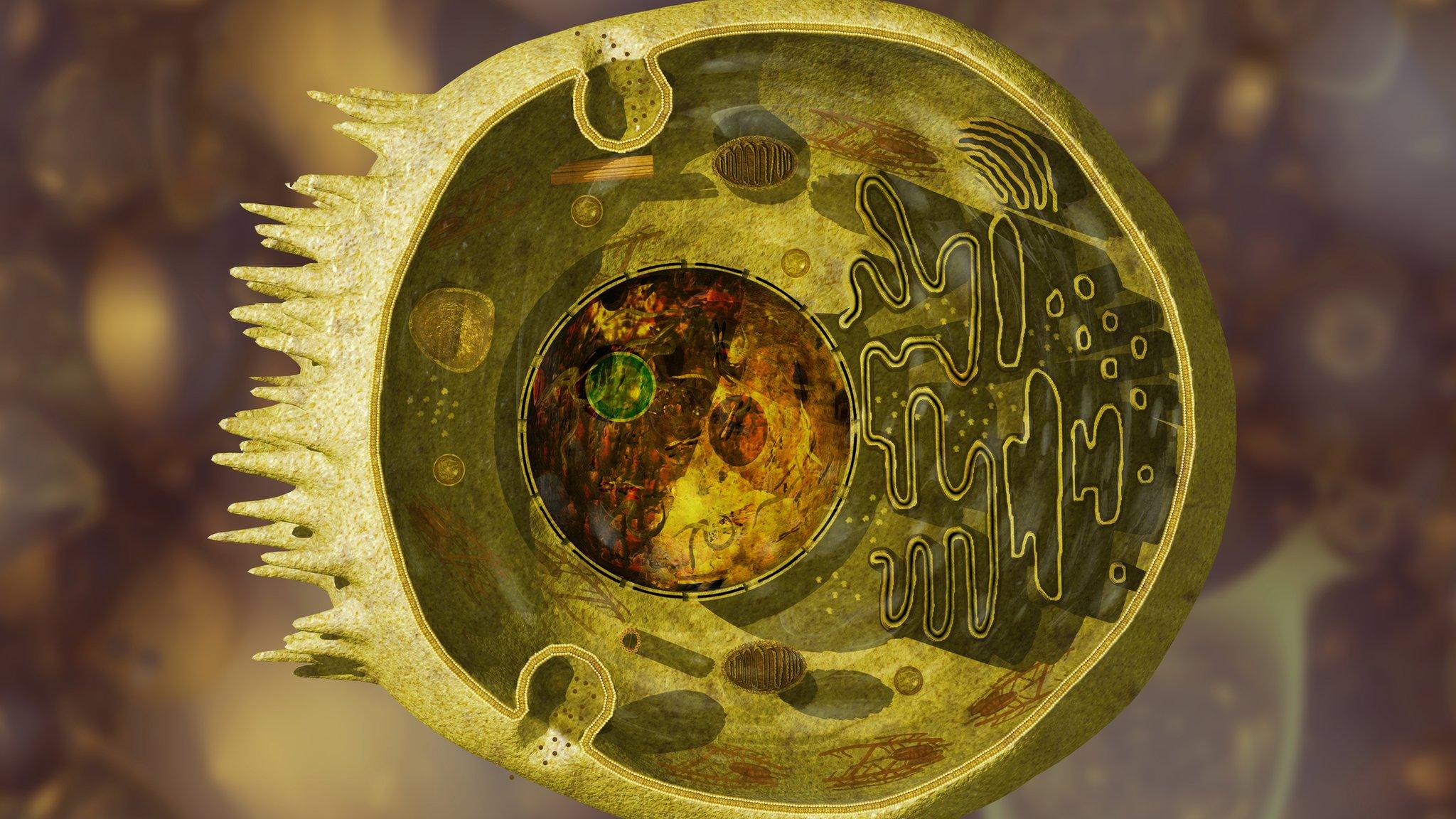

Today, scientists routinely use modelling to understand how different biological molecules interact, to probe the mechanisms of disease and to design novel drugs.

"The Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 2013 have made it possible to map the mysterious ways of chemistry by using computers," said the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, external.

"Today the computer is just as important a tool for chemists as the test tube.

"Detailed knowledge of chemical processes makes it possible to optimise catalysts, drugs and solar cells."

New medicines

Warshel told a news conference in Stockholm by telephone that he was "extremely happy" to be woken in the middle of the night in Los Angeles to find out he had won the prize.

"In short, what we developed is a way for computers to take the structure of a protein and then to eventually understand how exactly it does what it does," he told reporters.

Marinda Li Wu, president of the American Chemical Society, said the award was "very exciting".

"The winners have laid the groundwork for linking classic experimental science with theoretical science through computer models.

"The resulting insights are helping us develop new medicines; for example, their work is being used to determine how a drug could interact with a protein in the body to treat disease."

Martyn Poliakoff, vice-president of Britain's Royal Society, said the award was "important recognition" for a major advance in theoretical chemistry.

"Their novel approach combined both classical and quantum physics, and now enables us to understand how very large molecules react," he explained.

"This prize highlights the increasing role that theoretical and computational chemistry are playing in this area of science."

All three men spent varying periods at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK. Michael Levitt started his PhD at the Medical Research Council, external facility at the end of the 1960s.

Analysis by Jonathan Amos, BBC science correspondent

Persistence pays off. Michael Levitt did his physics degree at King's College London, and was then desperate to do a PhD at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. The LMB was where he could learn from "towering heroes" - the likes of Francis Crick, Max Perutz, John Kendrew and Aaron Klug.

But the 19 year old's requests to join the intellectual hothouse were repeatedly, but politely, rebuffed. Thankfully for the world of science, Levitt wouldn't take 'no' for an answer. He drove to Cambridge from London, and camped outside Perutz's office until the Nobel Prize winner would see him. Whatever Levitt said on that sunny Friday in April 1967, it clearly had an impact because the LMB relented and gave him his opportunity.

The first thing the lab did was pack him off to Israel to work with Shneior Lifson and a student of his - Arieh Warshel. These men were using computer modelling to try to understand the behaviour of large biological molecules.

Israel, Levitt says, had two profound influences on his life. The first - it was where he met his wife, Rina. The second - it was the place that set him on the research path that melds the worlds of computers and structural biology.

Asked for some advice to give young scientists, Levitt says: "Believe in yourself. I tell this to all the students I see: 'If you don't believe in yourself, how can you expect anyone else to?' Be passionate, and also be stubborn. Being stubborn is an important characteristic."

The obstinacy of a young man 46 years ago is today rewarded with a Nobel.

Dr Richard Henderson, a current LMB scientist, said the trio's work was hugely important.

"They came at it from different angles but with a common goal," he told BBC News.

"They developed computer mathematical models for the forces that hold together mainly proteins, but other biological structures as well. They listed all the forces between atoms, and then they put these into one big computer program and set it running.

"In this way, they could simulate in the computer the behaviour of real proteins as they folded and unfolded, as they bind substrates and ligands.

"They were really the first people to push this field forward, and today it has become a worldwide industry."

Michael Levitt himself said this success was due in large part to the spectacular performance of modern computing: "I've told people that the silent partner in this prize is the incredible development in computer power.

"When we started this, no-one had any clue that computers were going to become so powerful; no-one knew about Moore's Law.

"This incredible increase in computer power has taken everybody by surprise, and I think this is one of the reasons why our field has become so important. And it's just going to get bigger and bigger."

The LMB, now on a new site in Cambridge, is a major draw for those wanting to tackle molecular biology

- Published8 October 2013

- Published7 October 2013

- Published10 October 2012