A post-Higgs Cern has its eye on 'dark Universe' mysteries

- Published

- comments

Without these people, Englert's and Higgs' vision could not have been realised

There were curiously mixed feelings here at Cern in Geneva as the news of the Nobel prize in physics swirled through the tunnels and laboratories.

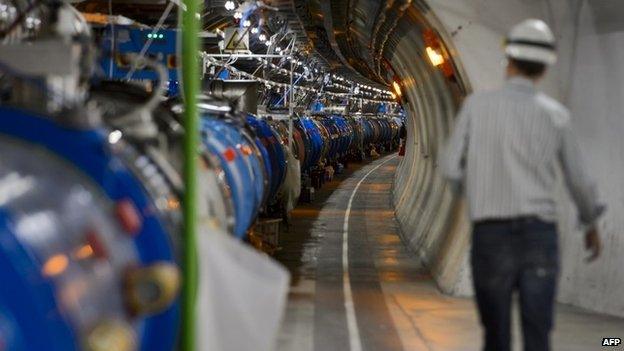

After all, the theories that earned the award could never have been tested without the massive experimental effort of the thousands of scientists working on the Large Hadron Collider.

In public, of course, everyone is delighted that Francois Englert and Peter Higgs won the award - it's a wonderful morale boost for this branch of science and rightly praises two popular and much-loved figures within it.

Peter Higgs is particle physics royalty, as the man whose name is borne by a critically important Boson.

And he earned undying devotion when he appeared here last year to hear the results of the hunt for "his" particle. The discreet dabbing of his handkerchief on a tear-filled eye and his bewildered expression when mobbed by journalists confirmed his status as a most reluctant star.

So no-one here is in the least bit surprised that at the key moment of potentially maximum publicity and media stress - the announcement in Stockholm - this quiet, shy, brilliant figure chose to slip beyond the reach of all cameras and calls.

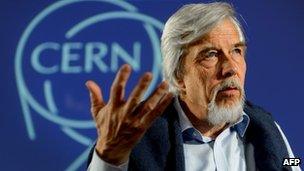

Rolf Heuer, director-general of Cern, told me that he reckoned that for Peter Higgs, "it's the fulfilment of a dream and he needs some time to digest this because I think he must be full of emotions".

David Shukman profiles the "shy but brilliant" Peter Higgs

For Cern and the Large Hadron Collider, he said, the prize, "means that we have been acknowledged for all the effort we have made in order to find that piece, the particle, and even more fascination in the general public - that's just great".

One of those caught up in the cheers-and-champagne throng celebrating yesterday's prize was Pauline Gagnon, a scientist with the Atlas detector.

"Everyone was screaming and shouting," she said, still elated several hours later.

Did she mind that Cern itself was not a winner? A weekend tweet from the Nobel committee, saying that organisations as well as individuals were eligible, had stirred up expectations.

For the occasion, Pauline even brought along her own medal, a Nobel chocolate in a shiny gold wrapper. Just in case; no one knew.

We're talking in Hall SM18 where the next generation of magnets is being checked - vast lengths of blue pipe are manoeuvred into giant testing rigs. The Large Hadron Collider is being upgraded and the magnets will steer beams of particles around the circular tunnel.

As usual, everything about the LHC is on a gargantuan, long-term scale, and Pauline seems determined to take a lofty view.

She and her colleagues are winners of a kind regardless of the precise names selected in Sweden, she believes. Theory and experiment go hand in hand, she says, "like two people on bikes taking it in turns to pull each other along". Englert and Higgs needed Cern to get where they did; Cern needed them to know where to look.

"So the Nobel prize is part of us," she says. "If we had not been there to prove that the theory existed, they would not have the prize - so we know we had our role to play there."

But she has one regret: a lost opportunity to raise a flag for the role of women in science. Only two women have ever won the Nobel prize in physics - Marie Curie and Maria Goeppert-Mayer. If the teams working on the LHC had been awarded a Nobel, too, "then another 1,200 women" would have won. "It would have been nice, but it didn't happen."

What next? This is where Prof Heuer becomes most animated.

Rolf Heuer: We currently understand only about 5% of the Universe

We're looking through plate glass windows into the Atlas control room, mostly empty now during the refit. Large screens carry CCTV images of vast cliffs of intricate metal in the cavern below. This is part of the machinery that helped pick out fleeting glimpses of Higgs bosons. The next operations are due in the spring of 2015.

For Prof Heuer, the Higgs discovery is just the start. It completed the physicists' Standard Model but that "just describes 5% of the Universe".

"Ninety-five per cent of the Universe - dark matter and dark energy - we have no clue what it is.

"I think after 50 years now, it's high time to open the window into the dark universe - that's next."

As we leave, I wonder what Peter Higgs would make of this kind of ambitious talk.

I assume he'd enjoy knowing that he'd had a pretty large hand in opening that door on the workings of the Universe, all those years ago, back with his paper in 1964.

But he's the epitome of modest. While a lot of people at Cern would have loved a Nobel, Higgs ran for the hills and didn't even take calls from the Nobel committee. One of the biggest advances in physics was the result of genius at its most humble.