European origins laid bare by DNA

- Published

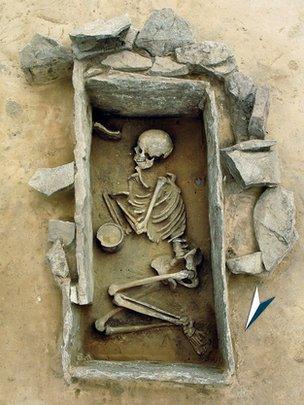

The emergence of the Corded Ware Culture involved the spread of people as well as ideas

DNA from ancient skeletons has revealed how a complex patchwork of prehistoric migrations fashioned the modern European gene pool.

The study appears to refute the picture of Europeans as a simple mixture of indigenous hunters and Near Eastern farmers who arrived 7,000 years ago.

The findings by an international team have been published in Science journal, external.

DNA was analysed from 364 skeletons unearthed in Germany - an important crossroads for prehistoric cultures.

"This is the largest and most detailed genetic time series of Europe yet created, allowing us to establish a complete genetic chronology," said co-author Dr Wolfgang Haak of the Australian Centre for DNA (ACAD) in Adelaide.

"Focusing on this small but highly important geographic region meant we could generate a gapless record, and directly observe genetic changes in 'real-time' from 7,500 to 3,500 years ago, from the earliest farmers to the early Bronze Age."

Dr Haak and his colleagues analysed DNA extracted from the teeth and bones of well-preserved remains from the Mittelelbe-Saale region of Germany. They focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) - the genetic information in the cell's "batteries".

MtDNA is passed down from a mother to her children, allowing geneticists to probe the maternal histories of populations. Geneticists recognise a variety of mitochondrial DNA "clans", or lineages, in human populations. And each of these lineages has its own distinct history.

The team's results show that indigenous hunter-gatherers in Central Europe were edged out by incomers from Anatolia (modern Turkey) some 7,500 years ago. A majority of the hunters belonged to the maternal clan known as haplogroup U, whilst the farmers carried a selection of genetic lineages characteristic of the Near East.

Around 6,100 years ago, farming was introduced to Scandinavia, which coincided with the appearance of Neolithic mtDNA lineages in that region too.

"In some ways agriculture was an obvious and easy way to go in the Fertile Crescent. But once you take it out of there, it involves an abrupt shift in lifestyle," said Dr Spencer Wells, director of the Genographic Project, external and an Explorer-in-Residence at National Geographic, adding that early agricultural groups were living "on the edge".

"They were basically taking crops that had evolved over millions of years in the Middle East and were adapted to that dry-wet pattern of seasonality and moving them into an area that was recently de-glaciated.

The Bell Beaker folk seem to represent a migration from south-west Europe

"It was no trivial thing to transfer crops such as barley and rye to the northern fringes of Europe."

Dr Wells thinks this precarious existence may be reflected in the spread of the lactase persistence gene, which enables people to digest milk into adulthood. Scandinavian populations have some of the highest frequencies of this gene variant in Europe, and it appears to have undergone strong natural selection in the last few thousand years - suggesting milk had a key nutritional role and the ability to drink it conferred an enormous advantage.

"What it implies is that the underlying farming culture is not stable. They are literally teetering on the brink of dying out," said Dr Wells.

Indeed, something does seem to have happened to the descendents of the first farmers in Central Europe. The DNA evidence shows that about a millennium later, genetic lineages associated with these Near Eastern pioneers decline, and those of the hunter-gatherers bounce back. Climate change and disease are both possibilities, but the causes are a matter for further investigation.

A second study, also published in Science, external by Ruth Bollongino at the University of Mainz, Germany and colleagues, implies that hunter-gatherer cultures persisted alongside farming cultures for 2,000 years after the introduction of agriculture to the region - with very little interbreeding between the two.

From 4,800 years ago, novel maternal lineages spread into the region, associated with the emergence of the Corded Ware people - who take their name from the inscribed patterns on their pottery.

The study suggests this culture was brought by groups moving in from the East. Scientists compared the mtDNA types found in Corded Ware people with modern populations and found distinct affinities with present-day groups in Eastern Europe, the Baltic region and the Caucasus.

A few hundred years later, a counterpart of this society swept in from the West. This ancient group, known as the Bell Beaker Culture, was in part responsible for the spread of a mtDNA lineage called Haplogroup H.

Scientists take many precautions to avoid ancient samples being contaminated with modern DNA

Largely absent from Central European hunters and scarce in early Neolithic farmers, H remains the dominant maternal lineage in Europe today and comparisons between the Bell Beaker people and modern populations suggest they came from Iberia - modern Spain and Portugal.

"Our study shows that a simple mix of indigenous hunter-gatherers and the incoming Near Eastern farmers cannot explain the modern-day diversity alone," said co-author Guido Brandt, from the University of Mainz.

"The genetic results are much more complex than that. Instead, we found that two particular cultures at the brink of the Bronze Age 4,200 years ago had a marked role in the formation of Central Europe's genetic makeup."

Spencer Wells explained: "When you look at today's populations, what you are seeing is a hazy palimpsest of what actually went on to create present-day patterns."

Dr Haak concurs: "None of the dynamic changes we observed could have been inferred from modern-day genetic data alone, highlighting the potential power of combining ancient DNA studies with archaeology to reconstruct human evolutionary history."

- Published23 April 2013

- Published15 May 2013

- Published27 April 2012