China: Opportunity and risk for hi-tech firms

- Published

- comments

The authors argue that China assimilates foreign technologies but also adds value and novelty

The UK Chancellor George Osborne said this morning that Britain tends to view China as a "sweatshop on the Pearl River".

In reality, he told the Today programme, "it's at the forefront of medicine and hi-tech and computing".

An official tweeted a picture, external of him, headphones on, gazing out at the grey urban landscape of Beijing.

To coincide with his visit - and that of science minister David Willetts - a new report calls for China to be seen as a land of scientific opportunity not a black hole of intellectual theft and cybercrime.

The study is by Nesta, external, a think tank founded to promote innovation, and it argues that the massive and growing scale of Chinese science means it is simply "too big to ignore"- spending about $500m on research every day and employing a quarter of the world's R&D workforce.

On his visit to Beijing, Mr Osborne said China was at the forefront of hi-tech

A graphic image of a vast frenzy of research comes from a corporate adviser quoted as describing China as a "boiling cauldron of people just trying stuff".

The headline facts are certainly impressive:

China now has the world's fastest supercomputer, the Tianhe-2. Its chips are made by Intel but it was Chinese expertise that brought them together.

Chinese scientists have developed the lightest material ever known, a kind of aerogel made with carbon nanotubes and graphene.

In just 14 years, China has gone from having just 1% of the world's gene sequencing capability to having nearly 50%.

One key factor identified in the report is the extraordinary size of spending on R&D - about $163bn last year, an amazing 18% increase on the previous year with further rises planned, with science seen as a central element of China's long-term strategy for growth.

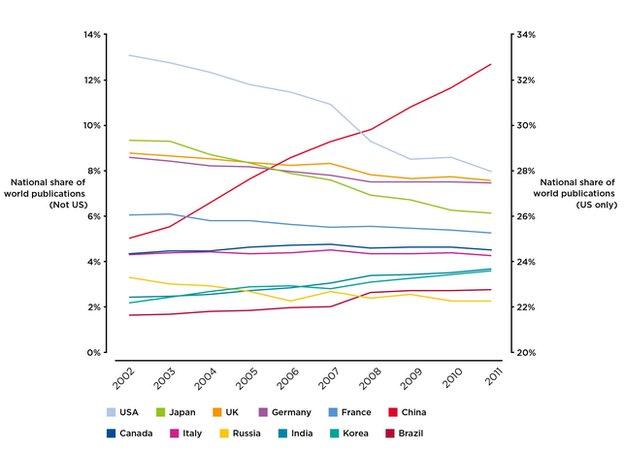

Measured by the number of patents applied for and secured, China is booming. By 2020, it could be producing more graduates than the US and EU combined. And by the same year, it may be publishing more scientific papers than the US.

But of course quantity does not mean quality. The study also notes a recent estimate that only 10% of Chinese engineering graduates meet international standards of employability.

So is China really a world leader in science or still a sweatshop? Or a bit of both?

The answer is complicated, according to the report. The image of China as a science superpower may be accurate but it is only one of several different ways to view the country:

China has also been called a "fast follower" - swallowing others' advances, quickly catching up but never leading.

Others say China's ability to advance will always be stifled by Communist Party rule, one-party control inhibiting the interaction vital to innovation.

Another perspective is that China is driven by "techno-nationalism", a desire not just to be competitive but also to secure "absolute advantage" through fair means or foul.

A fourth approach argues that China recognises the extreme challenges of climate change, pollution and resource scarcity and its investments in research are designed to yield long-term solutions , with global benefits.

The authors themselves argue that China should be seen as "an absorptive state", assimilating foreign technologies but then adding value and novelty to them.

But what about the risks?

The report acknowledges a darker side - the fears among hi-tech companies about the theft of their intellectual property. One business leader said "we don't feel ready yet to develop our 'crown jewels' IP in China". But he nevertheless supports long-term engagement there.

Chinese scientists say they have developed the lightest material known to science

A related threat is cybercrime - estimated, in a study for the Cabinet Office, to cost the UK £27bn a year. But the authors suggest the dangers may be overplayed, and may be of more concern to politicians than business people.

Overall, the report concludes, "the greatest risk for companies is of focusing too much on these downsides, and missing out on the enormous opportunities that China presents", and it calls for far closer collaboration.

People who've tried partnerships and have had their ideas or technology stolen may regard that perspective as overly rosy.

But a new kind of science gold rush is under way in China - and, as in every rush, there are fortunes to be made, and lost.

- Published14 October 2013